Update: 17 Feb 2014: Sanity has prevailed and the service has now been pulled.

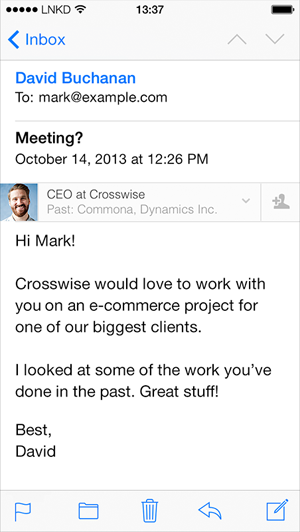

LinkedIn Intro has already become known by many names: A dream for attackers, A nightmare for email security and privacy and A spectacularly bad idea to mention but a few. Harsh words. The general consensus of people I’ve spoken to is that it’s fundamentally stupid and about the worst thing you could consider doing with your privacy. It looks like this:

You probably didn’t know this, but apparently you want a third party to access your email, pull some data out of it, manipulate the contents then send it on for you. That’s every email you send. Oh – and every email you receive too.

Others have outlined all the reasons why this makes about as much sense as tits on a bull, one of the more cohesive ones is LinkedIn ‘Intro’duces Insecurity which outlines 10 key reasons why they consider the approach to be pure insanity. In short, you’re handing control of your email over to LinkedIn and allowing them to read and modify the contents at will as you send and receive it. Surely this is some secret NSA plot to infiltrate private communications on a level never previously seen?!

What I haven’t seen yet though is an analysis of how the service is put together and what it actually means for your mail and your privacy. Let’s disassemble the thing, take an objective look at how it works and engage in some healthy speculation about what it means for privacy.

It’s not an app, it’s a profile

Let’s start here because one of the big questions I’m hearing is “Why would Apple allow this?” There’s an easy answer to that – they don’t. Apple in no way facilitates this feature and indeed it’s Apple’s security model which is sound enough that the only way LinkedIn can actually provide this feature is to mount a Man in the Middle attack (henceforth referred to as an MitM attack). Make no mistake, this is exactly what an MitM is; it is entirely dependent on introducing a third party into the middle of the communication between two other parties. In the security world we invest serious resources to protect against this form of attack – LinkedIn is actually asking you to opt into it. I know they don’t like this term but if it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, well, you know.

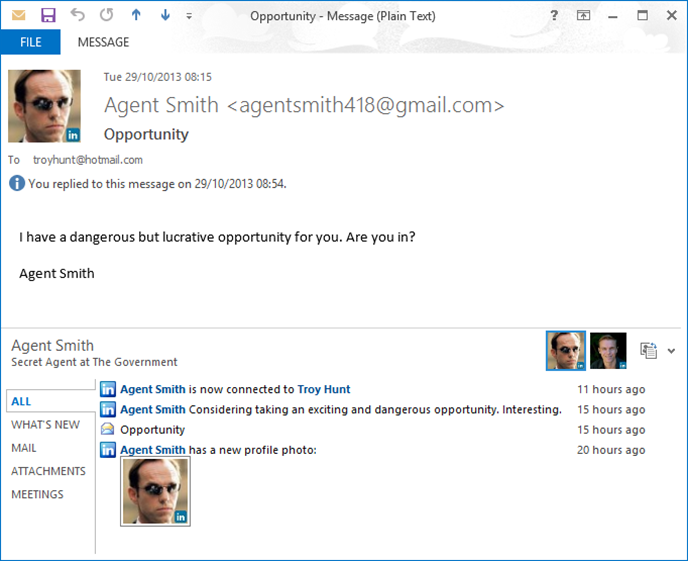

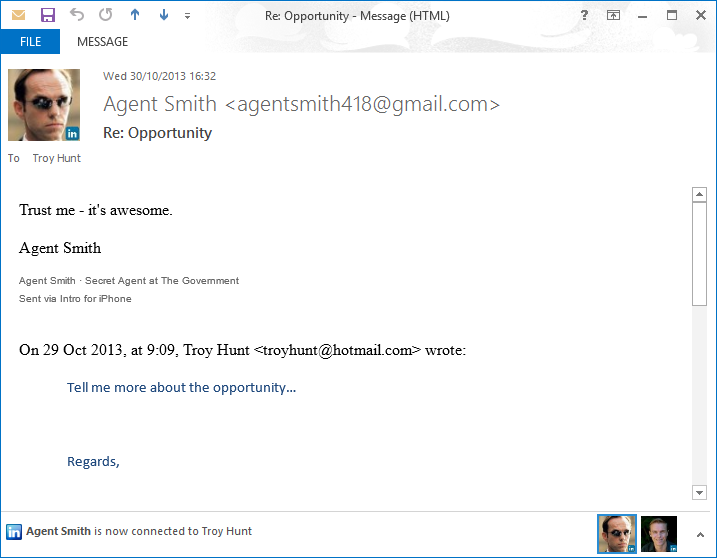

I’ll come back to Apple in a moment, let’s talk about the “feature” for a moment and to contextualise this I’ll point you in the direction of LinkedIn for Outlook. This is a “Social Connector” in that what it does is runs as an Outlook plugin so that it can do funky stuff like this:

“Agent Smith” is the pseudonym we’ll be using to test Intro and before you go looking for him, he’s already met with an untimely demise so as not to pollute LinkedIn’s system. What we’re seeing here is data that LinkedIn has on the participants in an email discussion and surfaces it in context at the bottom of the email. There’s one for Facebook too and there’s nothing wrong with this per se (assuming you don’t have a problem with seeing peoples’ public Farmville activity beside their serious corporate email), it’s simply making HTTP requests to the service and pulling back publicly accessible data.

You can do this in Outlook because Windows allows you so install all sorts of different things that interact with other standalone products. But in iOS, apps are sandboxed in such a way that this simply won’t fly; you can’t just add a third party connector into the mail app which then changes its behaviour. The only way LinkedIn were going to be able to achieve the same functionality was to manipulate the mail itself and that meant going back up the communication stack and getting their hands on the email before it even hits the device. Therein lies the MitM.

When you install Intro, you’re not installing an app from the Apple App Store and consequently you’re not coming under Apple’s purview. They’re not inspecting the app, they’re not approving it and they also can’t yoink it if they don’t like it. What you’re actually installing is a profile and that’s a fundamentally different proposition to installing an app. It’s also a very worrying proposition. Let me walk you through the mechanics of it.

“Installing” Intro

Let’s jump into it and I’m going to use a spare iPhone 4 and dummy email and LinkedIn accounts owned by our mate “Agent Smith” for this.

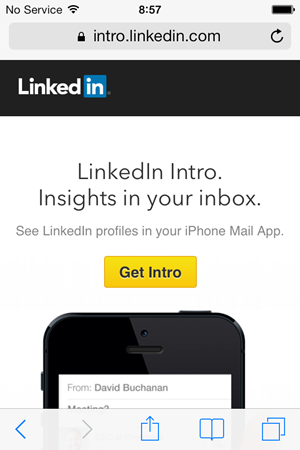

Firstly, everything kicks off over on intro.linked.com:

The Intro website is actually pretty neat and let’s face it, we all want to “be brilliant”, right?! Let’s get started:

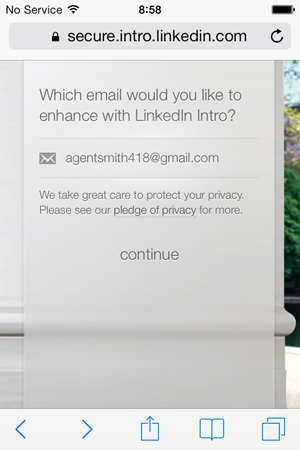

You kick off by entering your email address. From here on in, I’m “Agent Smith”, thank you very much:

It’s important to note here that Intro can’t MitM any old email account, it’s only Gmail, Yahoo! Mail, AOL Mail, iCloud and Google Apps. Fears of employees routing the corporate email through Intro are, for now, premature. Having said that, if they’re not actively planning how to make it available to services well beyond these, I’ll eat my hat.

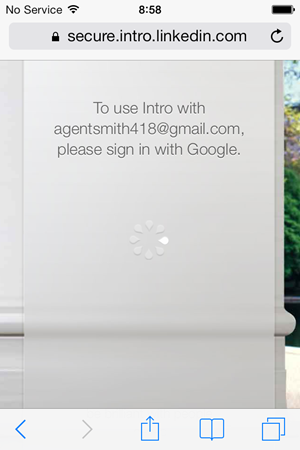

Moving on, Intro asks you to authenticate to the mail provider:

This is now just your classic OAuth token pattern so let’s sign into Google:

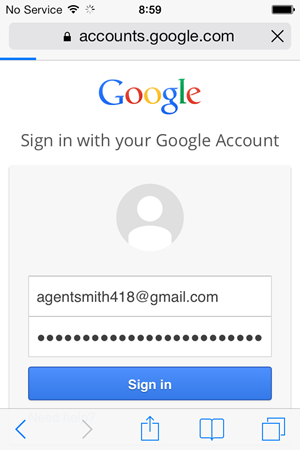

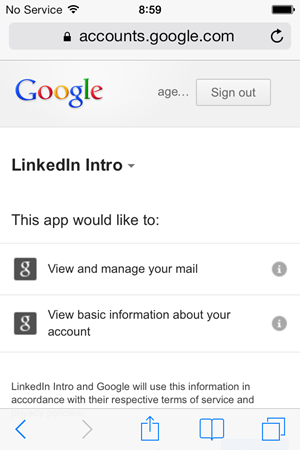

Here’s where we get to the pointy end; Intro would like to “View and manage your mail”. This is exactly what it sounds like it is and proceeding beyond here that’s going to give LinkedIn unbridled access to your mail which, of course, is what all the fuss is about:

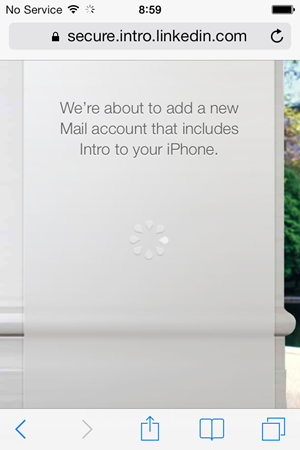

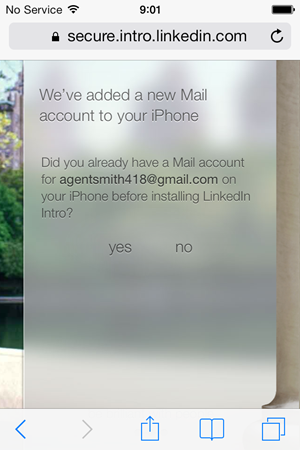

Moving on, what Intro actually wants to do now is create an all new email account:

This is important – Intro isn’t modifying email in storage and you won’t be able to go in later via the browser and see LinkedIn embedded within the mail client. They also make it quite clear that they don’t store your email (or your password, for that matter) and indeed with the model built the way it is, there’s no need to.

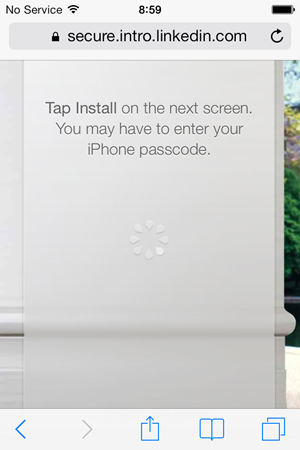

We’re going to get prompted to install that account so Intro sets an expectation of this up front:

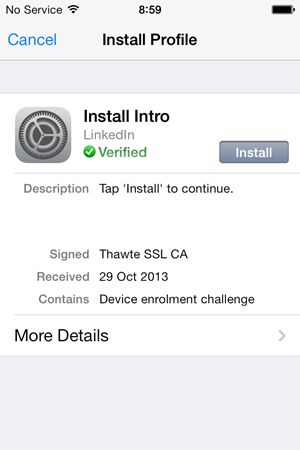

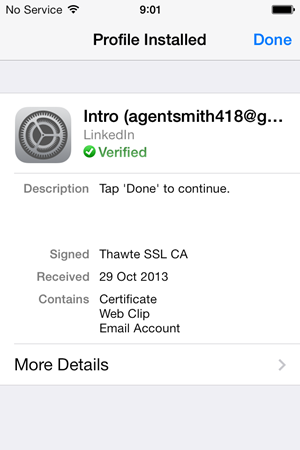

Here’s where a lot of the concern is being raised – Intro is now serving up a “profile” and asking the user to install it. What could you do with an iOS profile? Quite a lot actually, for example you could proxy HTTP traffic through another service, you could trust self-signed root certificates and in Intro’s case, you can install a new email account:

The problem, of course, is that you have no idea what’s actually been installed. For all you know this profile could be designed to siphon off your web traffic or install a rogue cert. Remember, Apple don’t need to review or approve profiles, installing them is based on nothing more than trust. Let’s a look at the details:

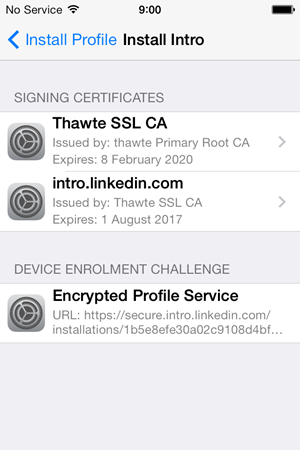

So we’ve got a couple of certs and an “Encrypted Profile Service”. Uh, okie dokie, sounds legit! Let’s install:

This has been referred to in Bishop Fox article I mentioned earlier – and rebuffed by LinkedIn – as being a “Security Profile”. The nomenclature is a bit semantic and certainly many profile updates do have security implications. Ultimately this is what will configure access to email via the Intro service so call it what you will.

Back to the Bishop Fox article, they summarise profiles as being able to do the following:

Intro works by pushing a security profile to your device; they’re not just installing the Intro app. They have to do this in order to re-route your emails. But, these security profiles can do much, much more than just redirect your emails to different servers. A profile can be used to wipe your phone, install applications, delete applications, restrict functionality, and a whole heap of other things.

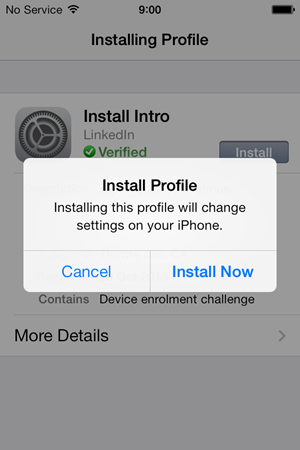

The subsequent rebuttal from LinkedIn effectively says “Yeah, but we don’t do that” and they’re right – they don’t. But the consumer doesn’t know that! Again, this is where much of the concern lies because profiles are just such powerful things not just because of what they can change in terms of device settings, but because they’re not provisioned via the App Store thus don’t go through Apple’s approval processes. I know I mentioned that earlier but it’s a key point as people tend to think that everything “installed” on their iOS devices is somehow reviewed and approved by Apple. Intro isn’t.

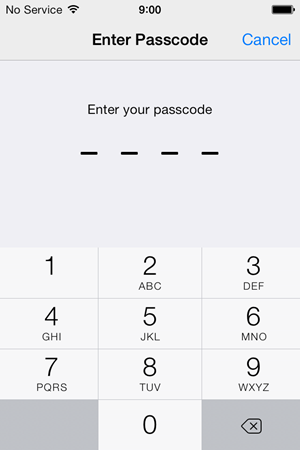

Moving on, installing a profile requires passcode validation which should be another indicator of just how significant an update like this is considered:

That done, the profile will be successfully installed and a confirmation message is displayed:

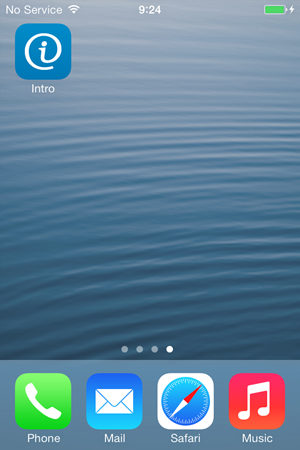

One other thing the profile does when it’s installed is creates a shortcut on the desktop:

This is not an app, it’s just a shortcut through to secure.intro.linkedin.com which then opens in Safari:

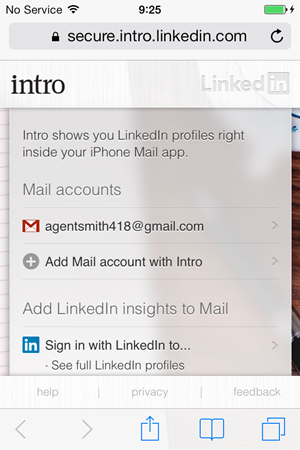

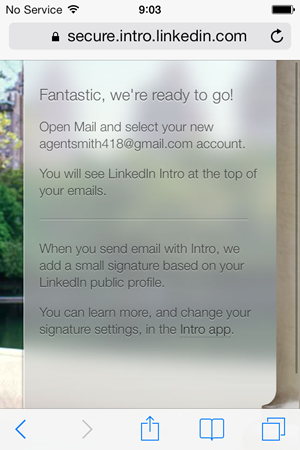

Once we exit out of the profile, we’re back to Safari and notified that a new mail account has been added. Usually this means that you’ll now have two email accounts: the original one on the phone and now the new one Intro added via the profile:

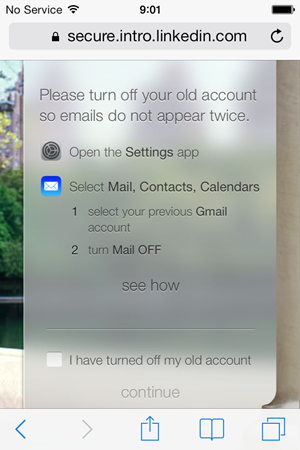

To avoid confusion, Intro now prompts you to turn off the original account:

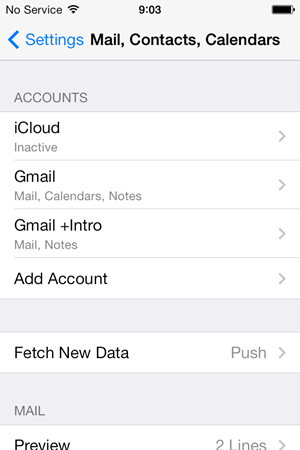

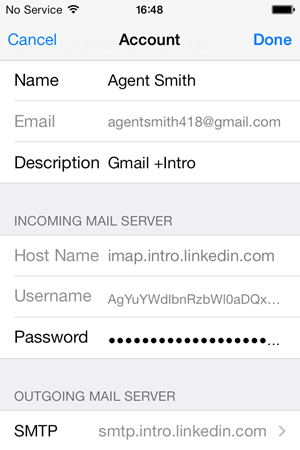

Indeed when we jump into the mail settings, there’s now a “Gmail +Intro” account in addition to the original Gmail account:"

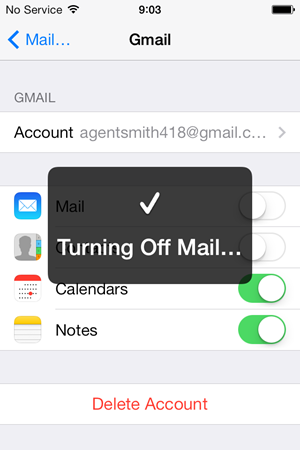

Let’s follow the earlier guidance from Safari and disable that Gmail mail account:

While we’re looking at mail, let’s check out what Intro has set up for us:

This is just an inbound IMAP account with an outbound SMTP server, both obviously on LinkedIn’s domain.

Back to Safari, tell Intro we’ve disabled the account and she’s all wrapped up:

That’s the entire setup process, let’s now see what she does.

Using Intro

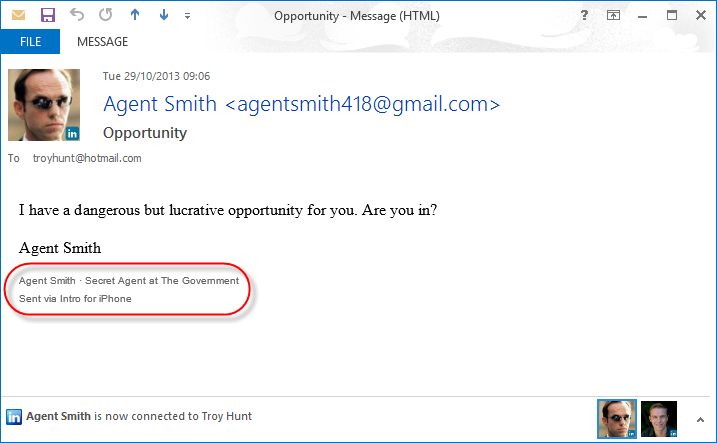

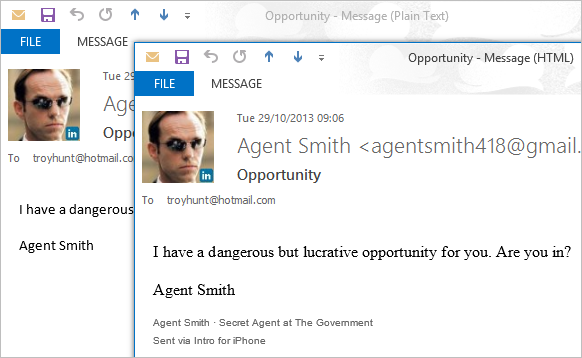

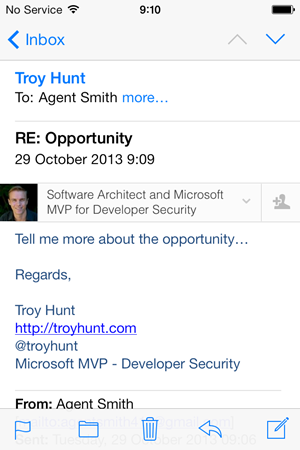

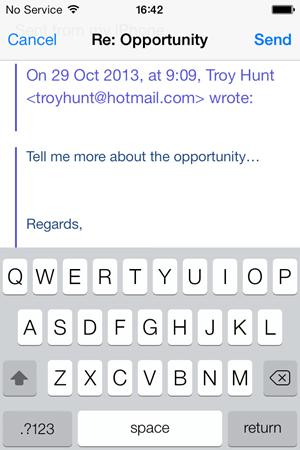

Now that we’re all setup, let’s get started using the service and the first thing we’ll do is to get Agent Smith to send me an email. Right back at the start of this post you saw what an email from Agent Smith looks like when opened in Outlook, here’s how it looks now post-Intro:

The obvious change is the signature which promotes the Intro service and includes Agent Smith’s LinkedIn name and professional headline which link to his profile. This is worth being aware of – the use of Intro is advertised to all recipients of emails sent from the iPhone in what I can only assume is an attempt at self-propagation. To me, this wasn’t clear during the setup process (I’m sure there’s probably some fine print on it somewhere) and of course you don’t see this when composing an email like you would a normal signature as it’s added after you send it. Your email is modified not just when you receive it via Intro, but also when you send it.

Why is this a problem? Well other than the obvious issue of LinkedIn having access to your mail, it also means there’s a risk of things like this happening:

Hang on – what the? Intro has changed the format of the email. More specifically, Intro has converted the message from plain text to HTML and it’s then up to recipient’s email client as to how they want to format it. Of course it has to do this – Intro can’t render fonts in different sizes and colours and add hyperlinks when it’s plain text. This isn’t a major thing, but it’s frustrating. I don’t like Times New Roman, I like a nice sans-serif font, dammit! The point is that once you have an intermediary manipulating the mail structure, things will change.

Just to be clear on exactly where the mail is coming from, let’s also take a look at the headers:

Received: from smtp.proxy.rapportive.com ([8.22.120.100])

by mx.google.com with ESMTPSA id ry4sm37728894pab.4.2013.10.28.15.05.43

for

(version=TLSv1 cipher=RC4-SHA bits=128/128);

Mon, 28 Oct 2013 15:05:45 -0700 (PDT)

Rapportive are the guys who “show you everything about your contacts right inside your inbox” and were acquired by LinkedIn last year. Inevitably it’s their smarts driving Intro and the name pops up here and there such as in the SMTP mail server above. The point is that it’s very clearly LinkedIn (or subsidiary) who are handling the mail and sending it out via their SMTP gateway.

Let’s move on and reply to the message because after all, the primary value proposition for Intro is that it brings LinkedIn data into email received by those using the tool. Let me respond from Outlook on the desktop and seek a bit more information. Here’s what it now looks like when it hits the iPhone:

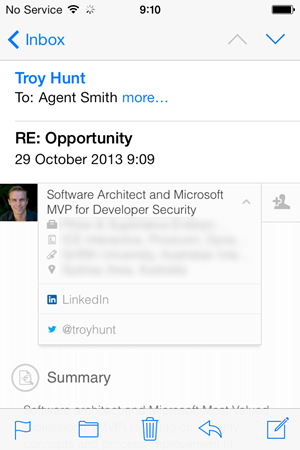

Right, now we can see the real value proposition for Intro kick in. My real LinkedIn profile – the one associated with my real email address – appears at the top of the mail. Frankly, I’m not real keen on losing 20% of my readable email space (yes, I measured it), and it is very overt. One thing for sure is that Intro grabs some very prime real estate in the message – you can’t escape its prominence.

Intro allows you to expand the banner it places in the email so that it can display various attributes of the sender’s profile:

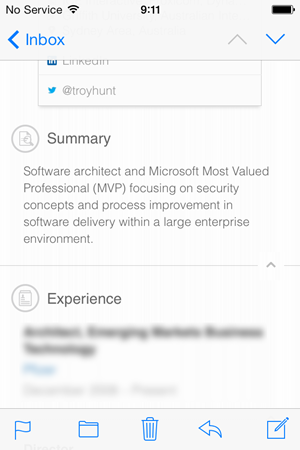

The template used to drive this is conveniently located over on GitHub Gist and essentially it’s just some data URIs for the images plus some CSS. Actually, it’s kind of clever the way they’ve done this and it works in their favour that they really only need to target one device in terms of compatibility so those data URIs work just fine. One side effect of this (and not one I’ve seen covered in the media to date), is that those data URIs in particular add quite a bit of bulk to the email, in fact it looks like an email such as the one above goes from a few bytes to many kilobytes which is quite a big jump on your data plan.

You get more of a sense of where this bulk comes from as you scroll down through the expanded panel:

And… keep scrolling:

Actually I skipped a big bit in the middle there and obviously the amount of content will depend on the profile of the person you’re viewing but regardless, it’s lengthy.

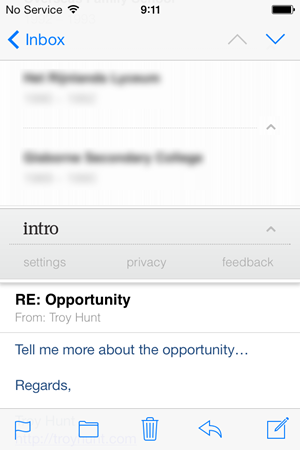

One of the things I wondered about with Intro was what happens when a participant of the program replies to a message? I mean does the recipient (who may well have nothing to do with Intro) get the same panel of data that was embedded into the markup? Easy answer – no:

Inevitably this has been modified again on the outbound connection from the device to Intro and it’s simply stripped out the markup it originally injected. It also doesn’t appear in edit mode on the iPhone when you’re actually responding to a message with an Intro banner in it:

This is actually a neat user experience (security issues aside) and it demonstrates that LinkedIn have invested a lot of effort in making this service what it is. In all fairness, it’s a very slick experience and I can’t imagine it being done much better with the technologies they have available to them.

So that’s the mechanics of the thing, now let’s tackle some of the security issues.

A self-defeating verification proposition

In the introduction of Intro, LinkedIn talks about the ability to verify the identity of the sender using their service (text bolded by me):

David says Crosswise would love to work with you. Is this spam, or the real deal?

With Intro, you can immediately see what David looks like, where he’s based, and what he does. You can see that he’s the CEO of Crosswise. This is the real deal.

Now of course this is just ludicrous; asserting that the mere presence of some HTML in an email somehow verifies and establishes the authenticity of the sender is entirely nonsensical. It’s not like, say, the public key infrastructure that underpins SSL where you have the whole concept of a certificate authority and a means of verifying the integrity of content served over the connection. There’s a good post on this by Jordan Wright where he likens it to saying “we’ve put a picture of a lock in your email, so you know for sure it’s secure” and, well, many of you already know how I feel about padlock icons.

In the link above, Jordan goes on to create his own spoof email by reconstructing the HTML complete with LinkedIn Intro “verification” of the identity that sent it. There’s nothing high tech or particularly clever about this but of course that’s the very point he’s making – this is not “the real deal” – this is a piece of HTML in a plain old email. That is all.

But it does raise some interesting potential…

Spoofing identities

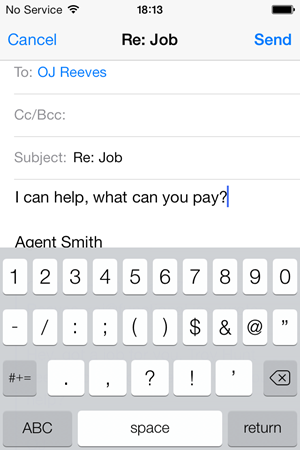

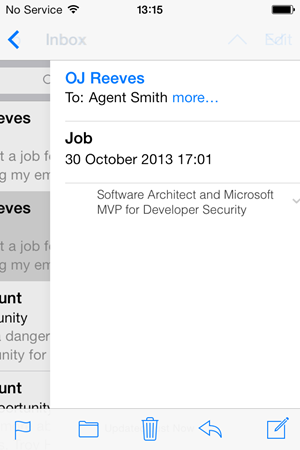

This is easiest explained graphically by this:

This is fellow security aficionado, good friend and all round nice guy OJ Reeves. OJ was happy for me to use him as an example of how this is very much not the real deal. OJ didn’t send this email to Agent Smith, I did. All I needed to do was construct an email where the sender’s email address was OJ’s. In this case I sent the mail with a reply to address that’s my own so when Agent Smith responds, the email comes to me yet this is what he sees:

You have to actually tap through on the “To” name to see the email address you’re actually sending this to and in the case above, it’s not OJ, it’s me.

This is very trivial and there’s nothing newsworthy in the ability to send email with anyone’s address as the sender or in the “reply to” field, but it makes an extremely pertinent point: Intro gives you no assurance whatsoever that the profile you see in the email is that of the sender. Of course this is no different to the level of assurance you get from the Outlook connector mentioned earlier, it’s just that they don’t MitM your traffic for that and as best I’m aware, they also don’t claim that it gives you assurance that the sender is “the real deal”.

Just one other minor thing while we’re looking at that email from OJ – sometimes when flicking around in mail you’ll see this:

This is OJ’s name, and it’s from OJ yet you’re seeing my LinkedIn profile info. It only flickers for a moment then correctly shows OJ’s info. Inevitably this is a redrawing issue on behalf of iOS mail, but it’s a bit disconcerting. Remember, we’re trying to see if this is “the real deal”!

In defence of the service

It’s worthwhile addressing LinkedIn’s defence of the service and particularly the article titled The Facts about LinkedIn Intro by Cory Scott. They copped a lot of flak very early so good on Cory and co for being proactive and having a shot at addressing the concerns. Anyway, the article talks about network segmentation, perimeter hardening, pen tests, TLS and so on and so forth and these are all undoubtedly good things. But effectively what it boils down to is “We know what we’re doing is risky so we’ve had to take extra precautions”. I just get the sense it’s a bit like saying that it hurts when you hit yourself.

The worrying thing though is that when you read statements like how they “challenged each other to consider possible threat scenarios” you kinda wonder – aren’t you doing this already? I mean aren’t these practices ingrained into the psyche of the developers as par for the course anyway? C’mon guys, you did lose those 6.5 million accounts last year, would that alone not suggest that by now you were thinking about threats anyway?!

I also find it odd that the defence talks about much what has been written being “purely speculative”. Of course it’s speculative – that’s what we do in security! We speculate that unprotected data may be observed or manipulated in transit so we apply SSL. We speculate that databases may be breached and credentials exposed so we use strong password hashing algorithms. The article does go on to support “healthy scepticism and speculation” so I don’t think the concerns others have raised are entirely lost, but it did strike me as an odd position to take in the opening paragraph.

Cory did also offer to help answer any questions I might have after I tweeted a query earlier in the week. To his and LinkedIn’s credit, Cory was very helpful on short notice and I’ve incorporated some of his feedback to my queries in this post. One of the issues that seems to come up a lot is around the “reading” of emails and LinkedIn asserts that they don’t “read” them per se, rather they look at the sender and they obviously change the format if required and inject some HTML at various points. Frankly, I think the whole “do they or don’t they read mail” misses the point: the capability exists to inspect and manipulate the contents of the mail and indeed this is exactly what Google asked us to grant permission to earlier on – to “view and manage your mail”. Look, despite all the effort invested in security and what we can only fairly assume to be the best of intentions, it’s this simple: LinkedIn has the capability to inspect and manipulate the contents of the mail – that’s the very design of the Intro service. By extension, if LinkedIn gets pwned (again), the potential is there for someone else to read and modify your email – that’s indisputable.

Another thing that strikes me as odd is that on the one hand LinkedIn can talk about all these excellent security measures (and there’s no argument that they talk about many good things), but then stand up a login form loaded over HTTP:

Yes, it posts to HTTPS but we know that’s useless. Facebook worked that out a long time ago after the Tunisian government kept pwning their users, I just can’t fathom why LinkedIn would do this. In their defence, this is apparently something they’re imminently addressing (in fact it may already be resolved for browsers in some locales) but it does seem to be an odd oversight in this day and age. And that’s another point worth nothing on the security front – what we deem to be “safe” today may not be what we deem to be safe tomorrow and it’s often only after serious incidents that sentiments change. That may well yet prove to be the case with Intro handling email.

In conclusion…

A lot of the contention around Intro is that it just feels a bit wrong on many different levels. It’s not just the MitM’ing of email or the manipulation of its contents or the inability to correctly establish “the real deal”, it’s the message that this is sending to everyday consumers. For one of the largest social media presences on the web to encourage hundreds of millions of users to install a profile on their iOS device sends a worrying message – that it’s ok. Desensitising people to the process of installing the profile sets a risky precedent. Trivialising the significance of installing profiles undermines so much of the positive work that the likes of Apple and Microsoft have done in sandboxing apps to protect from the very risks that this now introduces.

LinkedIn Intro may well be a neat tool for many people and I’m sure they’ll inevitably have millions sign up to it. The concept of entrusting your email with an external provider is nothing new. The big question is whether we’re really ready to trust our private email communications with a social media company with a strong focus on mining data. We worry about sharing small pieces of information with Facebook; are we ready to share every single email - every single attachment - with one of the world's largest social media companies? That Intro comes so closely after the NSA revelations where it’s now become clear that the US government is hell bent on getting their hands on as much data as possible is poor timing for LinkedIn, but opportune timing for those who may now be wondering just how much “sharing” of their data they really want to consciously opt into.