Another week, another major security incident with a significant website. So the news this time is that Zappos – those guys who sell shoes (among other things) – to folks in the US may have, uh, accidentally disclosed somewhere in the order of 24 million user accounts. Bugger.

Now of course at the root of this is inevitably yet more evildoers intent on breaking through website security for financial gain, activism or just plain old kicks. Regardless of the modus operandi of these incidents, the fact remains that a significant number of accounts have been exposed and there’s now the real possibility that usernames and passwords – perhaps your username and password – are going to be floating around the internet being seen by who knows how many people.

This, of course, is a problem because statistically there’s a better than average chance you’ve used that password in a number of other locations. Did you use it for eBay? Was it the same one you used for Amazon? Or even worse, is it your Gmail password and it can now be used to reset all your other passwords? If you’re asking yourself any of these questions right now, it’s time for a password manager which makes it dead easy to create strong, unique passwords across all your accounts so that the next time this happens – and there will be a next time – your credential exposure and your risk won’t go beyond that single site.

Is password reuse really that bad?

Let’s put some context around this from another recent major security incident; Gawker. Back in late 2010, somewhere in the order of a few hundred thousand accounts were exposed after Gawker was hacked. This, of course, may well prove to be a very small number in comparison to Zappos but it’s a significant number nonetheless.

What frequently happens in these hacking incidents is that the perpetrators proudly post evidence of their handiwork to the web for all to see. That’s right, every account is made public so that anyone can download them. Here’s Gawker, here’s Sony, here’s Stratfor and by the time you’re reading this, you may well be able to add Zappos to the list. Bottom line: expect confidential account information to be made public.

What happens next is that those leaked credentials start getting abused. After the Gawker incident, folks with breached accounts started unexpectedly tweeting about Acai berries. Why? Because they’d reused the same password between Gawker and Twitter and one of the 2 billion plus people who now had access to this information was using it to send Twitter spam. It’s that simple.

Now of course it could also be much worse than that; reuse the account on Amazon and some of those 2 billion people might start making other purchases on your behalf. Reuse it on Facebook and suddenly it’s very easy to start socially engineering your friends into clicking on links or installing software they wouldn’t normally do – after all, someone they trust is prompting them into action so it must be ok, right?

The bottom line is simply this: every time you reuse a password, it’s like sleeping with someone without “taking precautions”. Sure, it can make things a bit easier and you trust them to be “safe”, but you’re risking your own personal safety plus that of every other interaction you have in the future.

Password anti-practices

There are plenty of ideas out there about how you should be managing passwords: coming up with a phrase then picking letters from the words, substituting characters such a –> @ and S –> $, creating just a handful of passwords of different classes then reusing them (forums, shopping, banking, etc.), using information about the website to generate the password and so on and so forth.

None of these work consistently, here’s why:

- Anything dependent on memory – your memory – doesn’t scale. You may be able to recall 10 or 15 or even 20 phrases or patterns or whatever model you choose, but you have more accounts than this, even if you don’t realise it now.

- Website developers can be real bastards (bear with me) and make it impossible to use passwords generated by patterns. They may limit character length to very low limits or restrict you to a very limited character set. There are a lot of websites out there where you’re stuck with a 4 digit PIN.

- Nobody – nobody – is immune from getting hacked. Banks get hacked. Security forms get hacked. Governments get hacked. Thinking you can create a “class” of password as though every place you reuse it is “secure” is fundamentally flawed.

When you don’t have consistency, you create exceptions. When you have exceptions, you need a way of tracking and managing them which puts you back right where you started which ultimately only means one thing: The only secure password is the one you can’t remember.

The role of the password manager

A password manager is kind of like the old adage about putting all your eggs in one basket then watching it really, really closely. There are different products out there that approach the problem from slightly different angles but today I want to look at my personal favourite, 1Password.

In very simple terms, it works like this:

- You install the 1Password software on your PC / Mac / iPhone / Android.

- You create a “keychain” which is a file that will hold all your passwords.

- You dream up a single, very strong password with lots of numbers, letters, symbols, etc. – this is your “Master Password” which you memorise and guard with your life.

- You put all your passwords for all the sites you use into your keychain which you can then only unlock with your master password.

- You backup the keychain and sync it between devices using Dropbox.

The keychain is encrypted in an extremely robust fashion and can only be unlocked with the master password. If you lose this, you’re on your own – nobody is going to be able to help you unlock that file so you’ll have to go through a reset process on every single one of them. Of course this also means that anyone who gets hold of your keychain can’t do anything with it without the master password. For example, if the keychain is retrieved from the hard disk of the PC or somehow extracted from your Dropbox account, it’s worthless on its own.

Other general Q&A about 1Password can be found in their blog post about How Secure Is 1Password?

Simplifying password management

This is actually a very simple process; in fact it’s so simple it’s a whole lot easier than what you’ve been doing before, even if you could remember all your passwords.

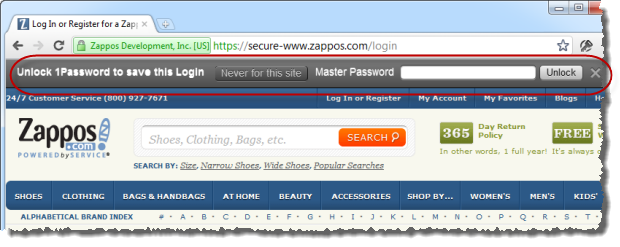

First up, I’ve got 1Password running locally on my PC. It integrates into the major browsers which means that when I login to a website it doesn’t recognise, say, oh, Zappos, this is what I see:

This is in Google Chrome, other browsers look slightly different. Anyway, you can see I’ve circled the 1Password bar which automatically appeared after logging in. I need to enter my master password to go any further after which I can give the account a name then that’s it – I’m done.

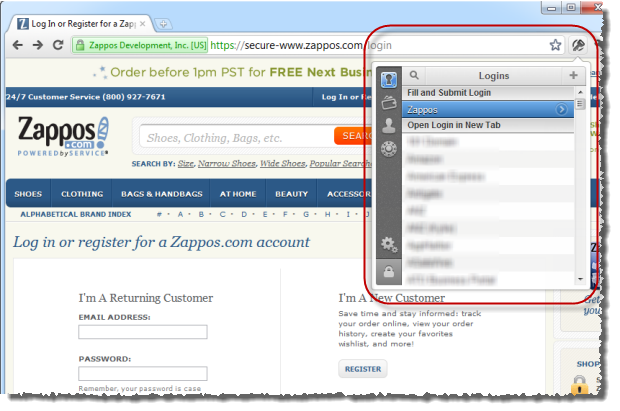

When I next come back to the site and want to login, I just hit the 1Password icon on the browser (it’s just to the right of the address bar), enter the master password then it automatically completes the login form – both username and password – then submits it for me:

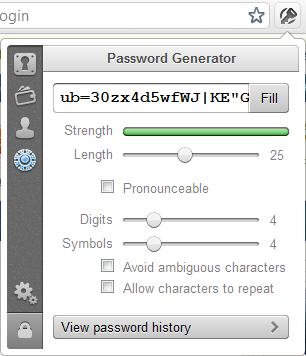

How easy is that?! Because this is so simple and because you then never need to actually remember passwords for sites like Zappos, you can start creating genuinely “strong” passwords and 1Password will help you out with this too. Back up on the menu above, the little dial like you’d find on a safe allows you to do this:

What this means is that you end up with a password something like “D[O62MA&RCWJ(Ihf3nk^e1bVS” <- this is a good password and it doesn’t matter one iota that you can’t remember it and that it would be a pain to type because you’re not going to be doing that any more, are you?

All of this works just fine on the PC (or Mac) but there are also equivalents for iPhone and Android and they’ll sync your keychain via Dropbox. The bottom line is that you can both keep your accounts secure and keep them with you wherever you go, choice of mobile platform dependent, of course.

The (very rare) caveats

The promise of only having “one password” is a bit grand, but it’s not too far off the mark. Any place where you can’t take 1Password is going to be an issue. Logging on to my PC while it’s locked is one example; logging on to my iTunes account on Apple TV is another one. In cases like this, I either end up with a shorter password that’s easier to type in (but I still can’t remember) or I use a memorable unique one when I really have to. But they’re rare exception – four or five at most.

But there are also other edge cases which can make things trickier for some people. Regularly using shared computers where you can’t run 1Password is a good example. The thing to keep coming back to with security is that you’re trying to strike this balance between making it too hard for the bad guys versus not making it too hard for you. For many people, that balance will mean taking different approaches; one size does not fit all. In a case like the shared machines, 1Password on a mobile device with shorter – but still random – passwords may be the best option.

Summary

Hopefully it will turn out that Zappos has done a good job of protecting their customers’ accounts and even though their database may have been disclosed, proper cryptographic storage will ensure passwords remain safe, or at the very least are not able to be cracked en masse. But regardless, they’re still telling customers to change their passwords anywhere else they’ve reused them. Clearly there remains a risk.

This is a repetitive story by now, one I’ve been on the receiving end of myself in the past. In fact it was that incident which prompted me into action and got me up and running on 1Password. I simply don’t worry about this sort of thing anymore – I have zero risk beyond individual sites.

Do yourself a favour, go and get yourself 1Password then spend a few hours moving your accounts in and resetting your passwords to something secure. Even if you weren’t affected by Zappos (or Sony or Stratfor or Gawker), tomorrow it’s going to be Amazon or eBay or PayPal or someone like that which will impact you and you’re going to have a whole world of new problems to deal with. Unfortunately, it’s inevitable.