Here's how it normally plays out: It all begins when a company pops up online and makes some sort of ludicrous statement related to their security posture, often as part of a discussion on a public social media platform such as Twitter. Shortly thereafter, the masses descend on said organisation and express their outrage at the stated position. Where it gets interesting (and this is the whole point of the post), is when another group of folks pop up and accuse the outraged group of doing a bit of this:

Shaming. Or chastising, putting them in their place or taking them down a peg or two. Whatever synonym you choose, the underlying criticism is that the outraged group is wrong for expressing their outrage towards the organisation involved, especially if it's ever construed as being targeted towards whichever individual happens to be the mouthpiece of the organisation at the time. Shame, those opposed to it will say, is not the way. I disagree and I want to explain - and demonstrate - precisely why.

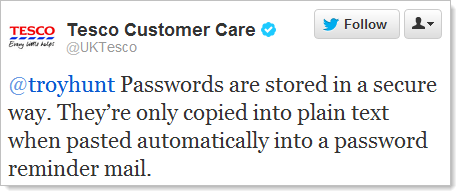

Let's start with a few classic examples of the sort of behaviour I'm talking about in terms of those ludicrous statements:

@passy We'd lose our security certificate if we allowed pasting. It could leave us open to a "brute force" attack. Thanks ^Steve

— British Gas Help (@BritishGasHelp) May 6, 2014

@psawers Yes, but they would need to attain this information through you, which once again, is a breach of our terms.

— Betfair Help (@BetfairCS) April 23, 2015

See the theme? Crazy statements made by representatives of the companies involved. The last one from Betfair is a great example and the entire thread is worth a read. What it boiled down to was the account arguing with a journalist (pro tip: avoid arguing being a dick to those in a position to write publicly about you!) that no, you didn't just need a username and birth date to reset the account password. Eventually, it got to the point where Betfair advised that providing this information to someone else would be a breach of their terms. Now, keeping in mind that the username is your email address and that many among us like cake and presents and other birthday celebratory patterns, it's reasonable to say that this was a ludicrous statement. Further, I propose that this is a perfect case where shaming is not only due, but necessary. So I wrote a blog post..

Shortly after that blog post, three things happened and the first was that it got press. The Register wrote about it. Venture Beat wrote about it. Many other discussions were held in the public forum with all concluding the same thing: this process sucked. Secondly, it got fixed. No longer was a mere email address and birthday sufficient to reset the account, you actually had to demonstrate that you controlled the email address! And finally, something else happened that convinced me of the value of shaming in this fashion:

A couple of months later, I delivered the opening keynote at OWASP's AppSec conference in Amsterdam. After the talk, a bunch of people came up to say g'day and many other nice things. And then, after the crowd died down, a bloke came up and handed me his card - "Betfair Security". Ah shit. But the hesitation quickly passed as he proceeded to thank me for the coverage. You see, they knew this process sucked - any reasonable person with half an idea about security did - but the internal security team alone telling management this was not cool wasn't enough to drive change. Negative media coverage, however, is something management actually listens to. Exactly the same scenario played out at a very similar time when I wrote about how you really don't want bank grade security with one of the financial institutions on that list rapidly fixing their shortcomings after that blog post. A little while later at another conference, the same discussion I'd had in Amsterdam played out: "we knew our SSL config was bad, we just couldn't get the leadership support to fix it until we were publicly shamed".

I wanted to set that context because it helps answer questions such as this one:

Why does it often take being named and shamed before they actually do something about these vulnerabilities. Still nice to see they have actually changed the site now.

— Timothy Dutton (@ravenstar68) December 17, 2017

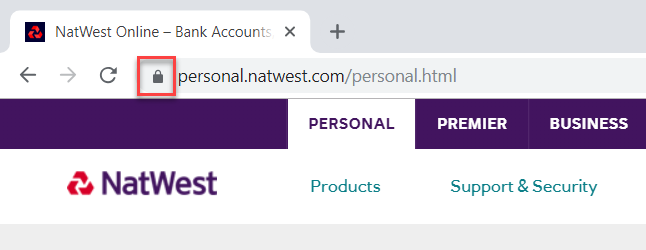

What public shaming does is appeals to a different set of priorities; if, for example, I was to privately email NatWest about their lack of HTTPS then I'd likely get back a response along the lines of "we take security seriously" and my feedback would go into a queue somewhere. As it was, the feedback I was providing was clearly falling on deaf ears:

I'm sorry you feel this way. I can certainly pass on your concerns and feed this back to the tech team for you Troy? DC

— NatWest (@NatWest_Help) December 12, 2017

And now we have another perfect example of precisely the sort of response that needs to be shamed so NatWest earned themselves a blog post. How this changed their priorities was to land the negative press on the desk of an executive somewhere who decided this wasn't a good look. As a result, their view on the security of this page is rather different than it was just 9 months ago:

Now I don't know how much of this change was due to my public shaming of their security posture, maybe they were going to get their act together afterward anyway. Who knows. However, what I do know for sure is that I got this DM from someone not long after that post got media attention (reproduced with their permission):

Hi Troy, I just want to say thanks for your blog post on the Natwest HTTPS issue you found that the BBC picked up on. I head up the SEO team at a Media agency for a different bank and was hitting my head against a wall trying to communicate this exact thing to them after they too had a non secure public site separate from their online banking. The quote the BBC must have asked from them prompted the change to happen overnight, something their WebDev team assured me would cost hundreds of thousands of pounds and at least a year to implement! I was hitting my head against the desk for 6 months before that so a virtual handshake of thanks from my behalf! Thanks!

Let me change gear a little and tackle a common complaint about shaming in this fashion and I'll begin with this tweet:

Ok England, look, this sort of stuff was funny for a while and I appreciate the laughs, but it’s starting to get a bit ridiculous. Can one of you please pop down to @santanderukhelp HQ and straighten this mess out? https://t.co/SlMnmFOnVw

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) April 18, 2018

Notwithstanding my civic duty as an Aussie to take the piss out of the English, clearly this was a ridiculous statement for Santander to make. Third party password managers are precisely what we need to address the scourge of account takeover attacks driven by sloppy password management on behalf of individuals. Yet somehow, Santander had deliberately designed their system to block the ability to use them. Their customer service rep then echoed this position which subsequently led to the tweet above. That tweet, then led to this one:

Please, just not another witch hunt on some poor clueless Customer Service rep... :(

— Andy ?️ (@AjaxStudy) April 18, 2018

Andy is concerned that shaming in this fashion targets the individual behind the social media account (JM) rather than the organisation itself. I saw similar sentiments expressed after T-Mobile in Austria defended storing passwords in plain text with this absolute clanger:

@Korni22 What if this doesn't happen because our security is amazingly good? ^Käthe

— T-Mobile Austria (@tmobileat) April 6, 2018

In each incident, the respective corporate Twitter accounts got a lot of pretty candid feedback. And they deserved it - here's why:

These accounts are, by design, the public face of the respective organisations. Santander literally has the word "help" in the account name and T-Mobile's account indicates that Käthe is a member of the service team. They are absolutely, positively the coal faces of the organisation and it's perfectly reasonable to expect that feedback about their respective businesses should go to them.

Social media accounts are the public face of an organisation. Their specific remit is to engage with the public who’ll likely have something to say about this policy.

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) April 18, 2018

This is not to say that the feedback should be rude or abusive; it shouldn't and at least in the discussions I've been involved in, that's extremely rare to see. But to suggest that one shouldn't engage with the individuals controlling the corporate social media account in this fashion is ludicrous - that's exactly who you should be engaging with!

A huge factor in how these discussions play out is how the organisations involved deal with shaming of the likes mentioned above. Many years ago now I wrote about how customer care people should deal with technical queries and I broke it down into 5 simple points:

- Never get drawn into technical debates

- Never allow public debate to escalate

- Always take potentially volatile discussions off the public timeline

- Make technical people available (privately)

- Never be dismissive

Let me give you a perfect example of how to respond well to public shaming and we'll start with my own tweet:

What is it with the anti-password-pasters today?! How is this sentiment permeating into organisations like @medibank in an era of so many password abuses? https://t.co/NXJGDyZomy

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) August 1, 2018

Business as usual there, just another day on the internet. But watch how Medibank then deals with that tweet:

Hi Troy, We just wanted to let you know that we've checked in with our digital team and they've let us know that they are already in the process of resolving this. We'll be deploying the ability to paste in about two weeks. Thanks again for the feedback! ☺️ Kindly, Sam.

— Medibank (@medibank) August 2, 2018

And in case you're wondering, yes, I did give them an e-pat on the back for that because they well and truly deserved it! The point is that shaming, when done right, leads to positive change without needing to be offensive or upsetting to the folks controlling the social accounts.

The final catalyst for finishing this blog post (I've been dropping examples into it since Xmas!) was a discussion just last week which, once again, highlighted everything said here. As per usual, it starts with a ridiculous statement on security posture:

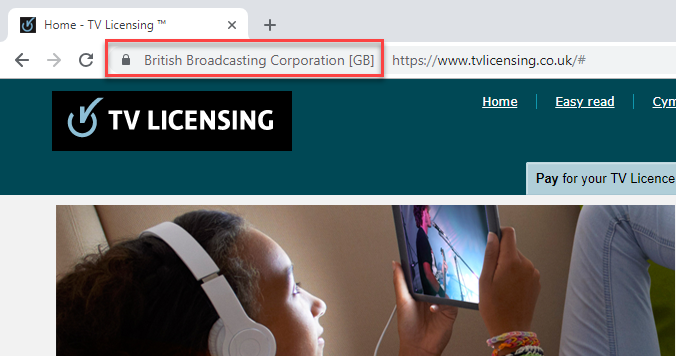

Our website is secure and security certificates are up to date. Pages where customers enter data are HTTPS. Non HTTPS pages are safe to use despite messages from some browsers (e.g. Chrome) that say they are not.

— TV Licensing (@tvlicensing) September 5, 2018

Shaming ensues (I mentioned my Aussie civic duty, right?!):

I don’t get British humour https://t.co/KJwLcq5R8Y

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) September 5, 2018

Once again, the press picks it up and also once again, people get uppity about it:

Also this is a social media account not a first response security account. Yes they are wrong, but as with T mobile and others- are we using a social media mgr to shame an org? Yes we need better awareness. But shame isn’t the way.

— Stella (@MlleLicious) September 6, 2018

'these guys' = some person working a minimum wage customer service job + raising the issue led to the issue being resolved. Calling them 'not bright' when they have to deal with whatever questions get thrown their way despite no real investment in them is not nice.

— Chris (@Modularized) September 9, 2018

And just to be clear, stating that "Non HTTPS pages are safe to use despite messages from some browsers" is not a very bright position to take whether you're on minimum wage or you're the CEO. Income doesn't factor when you make public statements as a company representative. Predictably, just as with all the previous examples, positive change followed:

That whole incident actually turned out to be much more serious than they originally thought and once again, the issue was brought to the forefront by shaming. I've seen this play out so many times before that frankly, I've little patience for those decrying shaming in this fashion because it might hurt the feelings of the very people charged with receiving feedback from the public. If a company is going to take a position on security either in the way they choose to build their services or by what their representatives state on the public record, they can damn well be held accountable for it:

I’m *absolutely* fed up of social media managers/comms teams taking control and making erroneous statements. If they have the balls to say something that’s demonstrably false and won’t back down when shown proof, be it on their head.

— Scott McGready (@ScottMcGready) September 6, 2018

Whether those rejecting shaming of the likes I've shared above agree with the practice or not, they can't argue with the outcome. I'm sure there'll be those that apply motherhood statements such as "the end doesn't justify the means", but that would imply that the means is detrimental in some way which it simply isn't. Keep it polite, use shaming constructively to leverage social pressure and we're all better off for it.