“The Cloud” is infinite.

It can scale to eternity.

It’s entirely redundant and resilient to any outage.

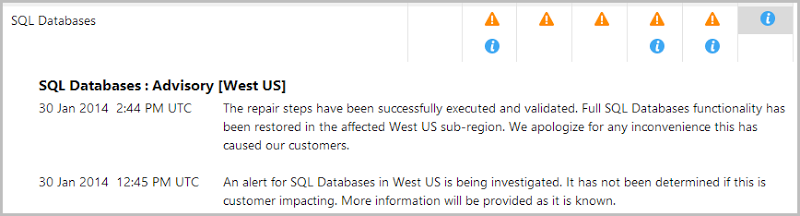

Except when it isn’t:

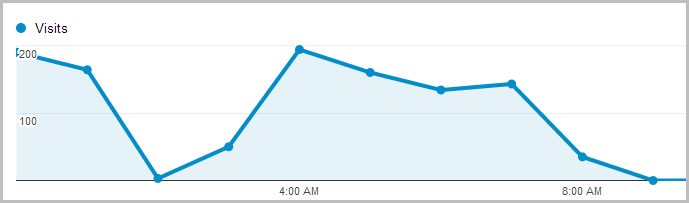

And when it isn’t, stuff kinda stops working:

Why is it always at 2am that stuff goes offline?!

Hey, it happens, even though there are those who don’t think it does / can but it presents an opportunity to filter through some of the FUD about SLAs and availability. Many times prior to this event I’ve seen gross misunderstanding about what SLAs mean particularly when we’re talking about multiple services with independent SLAs. Let me try and demystify some of this.

Understanding SLAs

First things first, in this context a Service Level Agreement is all about how and when the service you’re paying for is available. Typically an SLA talks about the percentage of uptime for the service, say 99.9%. Now that may sound like a lot, but do the maths – this is saying that you may well experience up to 45 minutes of down time in a month. It may happen all in one go. It may happen at your peak time. It may really, really suck.

This is how a typical SLA reads, this one being for Azure Web Sites:

Windows Azure Web Sites running in the Standard tier will respond to client requests 99.9% of the time for a given billing month. Monthly availability is calculated as the ratio of the total time the customer’s Standard web sites were available to the total time the web sites were deployed in the billing month. The web site is deemed unavailable if the web site fails to respond due to circumstances within Microsoft’s control.

The bold text is mine and it demonstrates an important caveat – there are many bad things you can do to your service that will break stuff and you have zero SLA coverage. Of course nor should you, either, the point is that SLAs are there to cover you when the provider themselves are at fault.

Now all that is well and good, but what happens if the SLA is not met? I mean for example, if your web site is off air for an hour in a month? Let’s talk about penalties.

Penalties

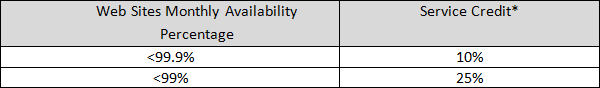

SLAs are a bit pointless unless there’s recourse available when they’re not met. This is the financial incentive for the service provider to make sure things remain stable. Typically, penalties involve some form of financial compensation and in Azure’s case that means that Microsoft will give you credit for your service in the following form:

In other words, if your site is offline for between 45 mins and nearly 8 hours, you’ll get 10% off your bill. More than that and it’s 25% off. Now that’s just off your web site hosting bill, not your entire Azure bill (that’s what the asterisk is for), which leads me to the next point: what happens when you have multiple services? How does this affect the SLA in aggregate?

Aggregated SLAs

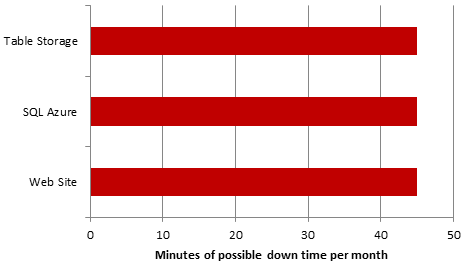

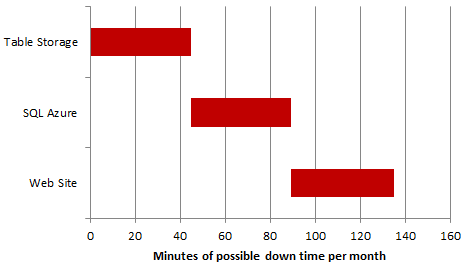

Let’s take a scenario and I’ll use my Have I been pwned? system from the outage period I outlined in the opening of this post. In this system I have a web site, a SQL Azure database and I also have table storage. For the site to function as intended, each of these components must be working. They also each have a 99.9% uptime SLA so what do you think that means in terms of potential outage?

I’ve seen many people think it means this:

“They all allow up to 45 minutes of downtime so my maximum outage is three quarters of an hour in a month, right?”

No, it means this:

There is no guarantee that the outage permitted under the SLA will happen across all services at the same time. This is really important because it means that the SLA I must expect for the service in its entirety is not 99.9%, rather it’s 99.7%. In other words, I have three times the possible outage window than what I would with only a single service.

Of course you can mitigate against this; perhaps there are still services the website can provide when the data tier is offline. Equally, you can now use geo-redundant read-only storage to connect to table storage in a different location if the primary one goes offline (although you need to manually orchestrate this). But these options don’t change the fact that by virtue of being dependent on three services, I’ve just tripled my maximum possible downtime within the allowances of the SLA.

SLAs with caveats

The above examples are pretty simple, others, yeah, not so much. For example, did you know that you can get a 99.95%* SLA for Azure Virtual Machines?

Ah, the mighty asterisk! Here’s what that really means: you can get that availability which halves the downtime as compared to the 99.9% of an Azure web site, but only if you have multiple instances of the VM. Of course this makes sense – more redundancy means you’re less likely to have stuff go offline and Microsoft is willing to make a financial commitment to that.

The problem, of course, is that if you then plug this VM into a SQL Azure database with a 99.9% SLA you then triple your potential downtime. That may be just fine in terms of the risk you’re willing to bear, the point is that even when higher SLAs are achievable, you still need to factor in the SLAs of other dependent services and add up the total possible outage of each one.

When the clouds go down

Clearly, as you saw in the opening of this post, “The Cloud” does go down. That was a minor one, impacting one service for a short period of time in a single location, but sometimes it’s far more significant.

A year ago Azure was hit with a pretty significant outage which was apparently the fault of an expired certificate. In November they had another rather serious one. But this is by no means a phenomenon exclusive to Azure. Amazon has had some whoppers too with a significant outage in August taking down some big names with it. Just last week one of the smaller players, Cbeyond, had an outage as well.

There are a lot of moving parts in these systems and every now and then, stuff goes wrong. Not often and even less frequently beyond what the scope of the SLAs provision for, the point is that services like these are not infallible. It’s not even a “cloud” issue – you’ve got a bunch of computers that all need to play nice together otherwise stuff stops working.

The point is that even though this new breed of technology gives us unprecedented access to easily accessible, low cost and highly redundant services, it’s not fool proof.

The cloud is not infinite, at least not all the time.