When it comes to our personal security, we’ve all grown a bit accustomed to keeping things on the down-low. For example, we cover the keypad on the ATM when entering our PIN and we shred our sensitive documents rather than throwing them straight in the trash.

We do this not because any one single piece of information is going to bring us undone, but rather we try not to broadcast anything which may be used to take advantage of us. That PIN could be used with the card to withdraw cash if someone gets their hands on it (or has a skimming device) and that bank statement you throw in the trash could be used by someone as leverage for identity theft.

And so it is with response headers, those little titbits of information your app is letting loose into the wild that you probably hadn’t even given a second thought. On the surface, this is innocuous data of no use to anyone, but dig a little deeper and suddenly it becomes quite useful to the evildoers.

Why is this important?

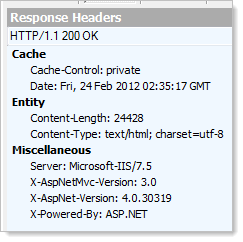

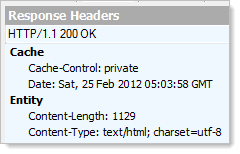

Let me give you an example: you’re cruising along with your website in its default configuration as far as headers are concerned which means that a heap of information about the site is being sent in each response. It probably looks like something like this (captured using Fiddler):

This is from one of the demo pages on telerik.com but it could just as well be from almost any website out there running the default configuration of MVC 3 and .NET 4 using IIS 7.5. But hang on – this is actually a lot of information to know about a site, particularly when it’s all implicitly communicated (i.e. it was probably never the express intention of the developers to disclose this).

Continuing our hypothetical example, one day a researcher pops up at a security conference and shows how a new zero-day attack can be used to exploit IIS. What’s more, the vulnerability is specifically with IIS 7.5. And only when it’s running ASP.NET 4.

Sound too hypothetical? A very similar thing happened just the other day, and it’s happened a number of times before that too. The level of specificity is often different (it might simply be “all IIS” that is vulnerable), but you can probably see where this is starting to go now: websites advertising their choice of web server and application framework also advertise their susceptibility when vulnerabilities are found.

But it’s about more than just vulnerabilities; how you might exploit certain features of one version of a framework may differ to another version. For example, changes to request validation in .NET 4.5 will mean the angle you might take to test for XSS vulnerabilities might change. Knowing the version of the framework in advance gives you a big head start in terms of which approach you might take when you have your evildoer hat on.

Contention and other implications

Many people will contest that this isn’t necessary; “security through obscurity”, they’ll scream. Not quite – that term is usually used to suggest that a particular practice of keeping something from view is the only thing standing between a “secure” system and a total breakdown of the aforementioned security. Putting all your administration content under “/MyHiddenAdmin” then not implementing access controls – now that’s obscure!

Not broadcasting headers takes us back to that original example about how we handle aspects of our personal security. It’s not about making a web app “secure” as if it’s one practice to rule them all, no, it’s about keeping information which could be used as part of a broader attack a little quiet.

The other pro-header-obfuscation argument is that you simply don’t need to be broadcasting this information. I mean it’s not used in any functional way by the browser and at the end of the day you’re just sending additional bytes down the wire that nobody actually needs. Oh – and you send it down with every single response the server sends. It’s small, but it’s unnecessary and it’s going to have a tiny negative impact on performance.

Still not convinced? Take a look at what the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force) has to say in RFC 2068:

Revealing the specific software version of the server may allow the server machine to become more vulnerable to attacks against software that is known to contain security holes. Implementers SHOULD make the Server header field a configurable option.

Plus you’ll also find the IIS Lockdown tool making recommendations to turn these headers off. Clearly the guidance from the people who should know is to keep things a bit quiet.

But at the end of the day, one of the compelling reasons not to broadcast headers is that it’s dead easy to turn them off. Maybe they’ll be used in an attack against your site one day, maybe they won’t, but if it’s a few minutes to turn them off and you’ll save a few bytes on each response, what’s to lose?

Headers ain’t headers

Not all headers are created equal and the way we turn them off within the Microsoft stack differs. Let’s recap on the ones we saw earlier on:

- Server: The web server software being run by the site. Typical examples include “Microsoft-IIS/7.5”, “nginx/1.0.11” and “Apache”.

- X-Powered-By: The collection (there can be multiple) of application frameworks being run by the site. Typical examples include: “ASP.NET”, “PHP/5.2.17” and “UrlRewriter.NET 2.0.0”.

- X-AspNet-Version: Obviously an ASP.NET only header, typical examples include “2.0.50727”, “4.0.30319” and “1.1.4322”.

- X-AspNetMvc-Version: Again, you’ll only see this in the ASP.NET stack and typical examples include “3.0”, “2.0” and “1.0”.

Let’s start with the server and in this case, the value obviously comes directly via IIS. Now keep in mind IIS doesn’t have to be running ASP.NET; it could be running PHP or node.js or even just serving straight old HTML pages. Clearly we’re not going to be disabling the server header anywhere within our ASP.NET configuration if we want to turn it off for all these frameworks.

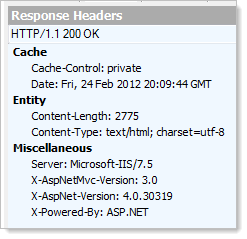

But before we start trying to turn things off, let’s create a baseline; here are the headers from a brand new ASP.NET MVC 3 app up and running on my local IIS:

Now, back to the server. The easiest way to get rid of that pesky server header and ensure it stays gone across all the various frameworks IIS will run is to install UrlScan. This tool will do a bunch of different things for you around how IIS handles requests but for today, we’ll just to fire up a text editor and take a look at the config file which is located over at C:\Windows\System32\inetsrv\urlscan\UrlScan.ini. What we want to do is find the “RemoveServerHeader” setting and configure it to be “1”. Let’s take a look at those headers now:

No more server!

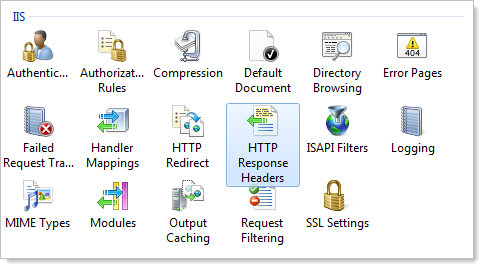

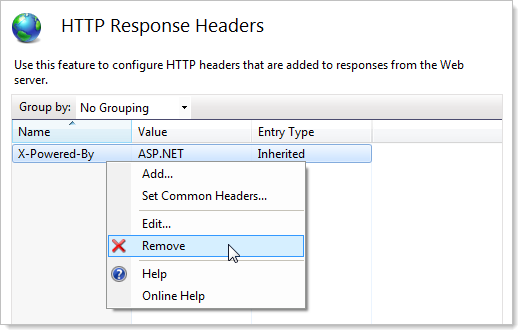

When it comes to X-Powered-By, this one is actually easily configurable straight out of the box in IIS 7.x, just jump right into the IIS configuration of the website and locate the “HTTP Response Headers” item:

And from there it’s pretty self-explanatory:

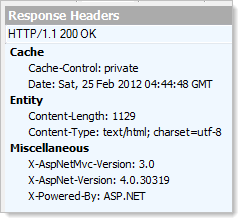

Moving onto the ASP.NET version, this one is a piece of cake because it’s simply a configuration item in the web.config:

<system.web> <httpRuntime enableVersionHeader="false" /> </system.web>

The MVC version is also easy, although it does require us to touch code. Over in the Global.asax, we want to jump into the Application_Start event and add the following:

MvcHandler.DisableMvcResponseHeader = true;

Very simple, and with all these in place we’ve now trimmed the headers down so there’s absolutely nothing of any interest left:

A little side-note before we move on: there are many different ways of doing the same thing. For example, some things differ a little in IIS 6. Then there are approaches such as Howard van Rooijen's “CloakIIS” which wrap it all up in a single handler (although I’ve personally had mixed results with this approach). Some of these may be harder or easier depending on your version of IIS, ASP.NET and the hosting model you use (i.e. if UrlScan is even available to you). Ultimately though, it’s a means to an end and if that end means these headers aren’t broadcast, then however you approach it is just fine.

Checking your headers with ASafaWeb

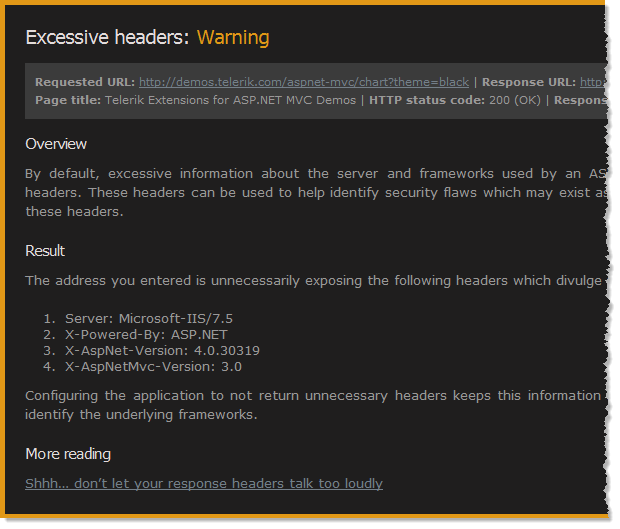

Because this is one of those easy wins in the “effort versus reward” security ROIs, I’ve gone ahead and built a scan for excessive headers into ASafaWeb. What it means is that scanning a site like the Telerik example from earlier now returns a warning like so:

Why a warning? It’s simply not in the same league as serious configuration risks like exposing stack traces or ELMAH logs. Actually, in terms of severity it’s more like the other warning ASafaWeb currently picks up – HTTP redirecting to HTTPS. In both cases, be aware of the risk, understand it, attempt to mitigate it but if you can’t, it’s not a biggie.

A quick comment on ASafaWeb because I just know that a curious individual somewhere will raise this: asafaweb.com returns a server header. The problem in this case is that ASafaWeb resides on the very excellent AppHarbor hosting service and being a true cloud hosting model, it has some clever network load balancing appliances sitting in front of the web servers. Try as I might to remove or change the server header, it’s being added back in downstream of the web server which I assume is happening at the appliance in front of the servers.

Summary

All of this brings us back to the mantra of applying security in layers. It’s about mitigating risk at each opportunity and in the case of these headers, it’s dead easy to remove them thus providing one small but tangible advantage. There will be those that dismiss this practice (indeed I came across many when looking for material for this post), but frankly, unless they can articulate a downside (which I haven’t seen expressed), there’s no reason not to strip these headers out.

Useful references

- Removing Unnecessary HTTP Headers in IIS and ASP.NET

- Cloaking your ASP.NET MVC Web Application on IIS 7

- How to remove Server, X-AspNet-Version, X-AspNetMvc-Version and X-Powered-By from the response header in IIS7