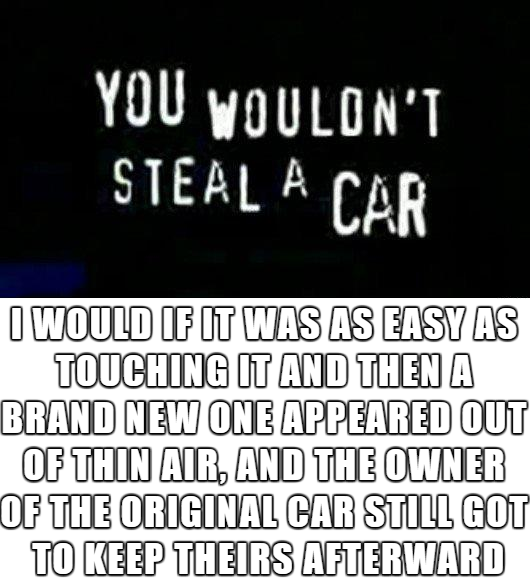

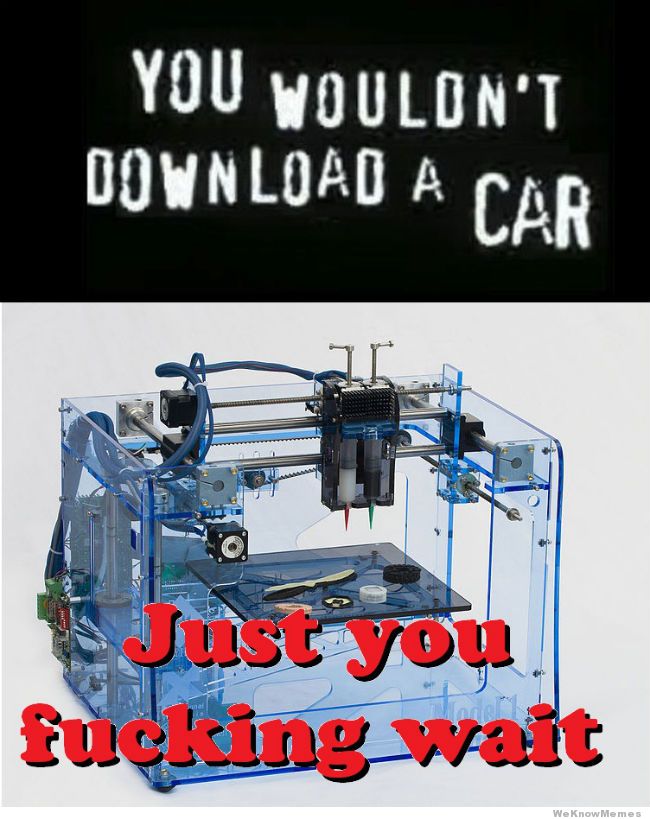

Remember the anti-piracy campaign from years back about "You Wouldn't Steal a Car"? This was the rather sensationalist piece put together by the Motion Picture Association of America in an attempt to draw parallels between digital piracy and what they viewed as IRL ("In Real Life") equivalents. Here's a quick recap:

The very premise that the young girl sitting in her bedroom in the opening scene is in any way relatable to the guy in the dark alley sliding a slim jim down the Merc's door is ridiculous. As expected, the internet responded with much hilarity because no-way, no-how are any of the analogies in that video even remotely equivalent to digital piracy:

And even if they were - even if you could directly compare the way both a movie and a car can be illegally obtained then yes, of course people would do it!

Setting aside for a moment the fact that the music in this piece was itself pirated (or at least misused in such a fashion that it resulted in the rights group that produced the video being fined), clearly these analogies are terrible. Now don't get me wrong - I'm not making these points in defence of piracy - rather it's to draw attention to the fact stated in the post's titled: IRL analogies explaining digital concepts are terrible. I got to thinking about this again over the weekend after watching responses to this blog post:

Regarding the case of the 19-year-old Canadian bloke accused of "hacking" by modifying the URL to pull down other documents, I wanted to write down some thoughts on it: Is Enumerating Resources on a Website "Hacking"? https://t.co/zwTj9eULd1

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) April 19, 2018

You can read the details in that post, what matters here is that the mechanics involve someone incrementing an identifier in a URL in order to download another resource. (This isn't just about the Canadian bloke either - and this is critical as people focused on him - but other noteworthy cases that demonstrated enumeration too.) Sometimes, the resource being accessed via enumeration isn't intended to be public, sometimes the person involved knows that and sometimes they highly automate the process to pull down large volumes of data. That's really the whole thing in a couple of sentences yet over and over again, people deferred to IRL analogies in an attempt to explain things. As I read these, I kept coming back to how totally irrelevant they often are; I've actually made a really conscious effort over recent years to avoid this pattern, particularly when responding to media queries the non-tech public will then read because frankly, they're extremely misleading.

For example, there's the assertion that leaving a resource publicly accessible is the equivalent to leaving your front door open:

Is it breaking and entering if the door is wide open?

— Bradley Geldenhuys (@bradgcoza) April 20, 2018

The implication being that if a door is left wide open then it's not breaking and entering, except that it actually is:

Burglary is typically defined as the unlawful entry into almost any structure (not just a home or business) with the intent to commit any crime inside (not just theft/larceny). No physical breaking and entering is required; the offender may simply trespass through an open door.

But that's actually an IRL misunderstanding rather than a poor digital analogy. If we suspend reality for a moment and imagine it wasn't breaking and entering to walk into someone else's unlocked house, the argument falls apart when you consider the premise of enumeration is that something is actually downloaded from the site as well. I won't dignify that with an analogy about it being equivalent to taking something from the house because in the digital world the "taken" thing is still there!

After reading the article, I think these "hacks" are a bit like walking into a house finding the door unlocked ... and then proceeding to wander around. Is that breaking and entering? It's definitely getting greyer the more you wander.

— Shawn Hartsock (@hartsock) April 20, 2018

Here's a true story: I was at a BBQ on the weekend and whilst we were sitting outside eating our sausages, an intruder made their way in through an outwardly-facing bedroom door then into a brightly-lit study facing a courtyard full of very surprised looking adults. The moment he was in that first room, he was trespassing and had anyone caught him there, it would not have been a polite conversation. But the whole premise of finding someone's physical door unlocked in the first place just doesn't translate:

To put into a metaphor @jteshart used, we need to differentiate checking that door is locked by rattling the doorknob, or doorknobs, or telling people that the door is unlocked (like these two cases potentially in courts) from breaking in, stealing the money, and spending it.

— dragosr (@dragosr) April 21, 2018

I mean think about it - if you found someone walking around the outside of your house trying each door, would you say "thank you good sir for making sure my security was alright" or would you call the cops? Exactly.

Is checking for unlocked doors "breaking-and-entering"???

— Samuel Movi (@samuelmovi) April 20, 2018

When the cops (eventually) arrive, the person "checking for unlocked doors" is not going to want to stick around. Conversely, I've had many discussions with companies where someone has identified security vulnerabilities in their things and not only have I been happy to talk to them about it, the company in question has usually been pretty grateful. Reckon that's how you'd react when finding a stranger jiggling the lock on your front door? Or what if they actually did enter your house like BBQ guy from before?

If my door has no lock, is it ok for anyone to walk in uninvited? With no malicious intent? I am so confused about this...

— Everything's connected (@oley) April 20, 2018

I can tell you exactly how that eventually panned out and it involved a lot of fingerprint powder! Short of a friendly neighbour who you know and trust wandering over because you've left the back door open, this just simply doesn't translate. And what if you have one of those "Welcome" mats on your door step?

If you don't have a lock on a door that says "Welcome! Please enter", it's different to not having a lock on a door saying "Restricted area. Keep out!". Going through the first door without knowing you've been misled, doesn't qualify as "exploiting a vulnerability".

— David Metcalf (@dlmetcalf) April 21, 2018

No - that doesn't mean everyone is welcome! IRL is full of contradictory security indicators because the same house with the welcome mat also has a sign up saying they don't want door-to-door salesmen and beware of the dog (which may or may not exist). But we as humans understand the IRL meaning of these things.

The same irrational house analogies extend to the car as well:

In Germany, it is forbidden to leave the car unlocked or the convertible opened. Tho, it is not forbidden to leave your servers wide open.

— Little Bobby Tables (@KiPos_info) April 21, 2018

One of the big problems with trying to compare digital security in the context of a web asset to physical security is that whilst the former can be tested from absolutely anywhere, the latter requires immediate proximity. The threats are totally incomparable. Then there's the fact that absolutely everyone who has a car knows how to lock it because it's a simple binary state achieved with a consumer-friendly device; lock, unlock. Lock, unlock. Easy. This in no way compares to the nuances of securing increasingly complex digital assets running on the internet.

It's complicated, and a not brilliant analogy is if someone accidentally leaves their car unlocked and the windows down and you reach in and take something to "prove" you could, is that really stealing? "But it was publicly accessible and I didn't pick locks or break the window!"

— Infinity+1 - Scott Williams (@ip1) April 21, 2018

No, it's not a brilliant analogy! Not just due to the aforementioned points, but also because you can walk down a street, look at a car, see the windows down and reasonably conclude that the windows are down with nothing more than your eyes! Testing for enumeration risks requires conscious, deliberate effort and if successful, results in you gaining access to material that wasn't intended to be in your hands. It'd be like if you looked at a car with the windows down and suddenly the owner's wallet was in your hands... except it's not because IRL analogies are terrible!

And then there's the whole "inadvertent security violation" analogy:

Imagine getting accused of sexual harassment for seeing your neighbour naked through the curtains they left open...

— Rich (@Canovel) April 20, 2018

These analogies miss the nuances of IRL; I was sitting outside on my balcony having a cold one recently and the neighbour walked past an exposed window with his gear on display. Putting aside for a moment the fact that I never, ever want to see that again, nobody IRL is going to accuse me of anything nefarious for experiencing that one frightful moment. But if I sit there with a set of binoculars and an infrared camera then the game changes somewhat. It just doesn't translate to the digital world.

Getting back to enumeration, in my original post I pointed out that the time to stop probing for an enumeration risk is when you identify one piece of data you shouldn't have access to.

@troyhunt - im not sure that accessing just one unauthorised record is OK - is it fine to take only one sweet from a shop - yet more than one is stealing ?

— John Middleton (@jmidd) April 20, 2018

This falls apart in all the same ways as the anti-piracy campaign did; if you steal a lolly (or a car), then the original owner no longer has that thing. We learn this as children - "Don't take your sister's toy away from her because she'll no longer be able to play with it and she'll start crying and etc etc". Short of a sanctioned penetration test on a candy store, there is no circumstance in which walking out with someone else's sugary treats is ever ok - that's not how any of this works!

The same argument that physical access to an IRL thing is incomparable to a digital one holds true here too:

If you see a list with sensitive information on the desk in a store, is it ok to copy it? The store is made publicly available but it doesnt mean you can do what you want. But the owner does also have a responsibility.

— Tore Andre Rosander (@RosanderTore) April 20, 2018

Placing someone else's things physically in your own hand whilst you're standing in their store is not analogous to copying their ones and zeros from the (perceived) sanctity of your own home. And as for the store owner's responsibility, you can walk into any store any day of the week and see things they'd rather you not reproduce and this works because we have very different views of trust IRL to what we do online. The same goes for other documents you might observe publicly:

Consider a bad analogy. Attorney seals printed client confidential data in envelope, pins to cork board impost office with hand written instructions “do not open unless you are the intended recipient.” Due care has been taken? Crime to take envelope and read content?

— Bill E. Ghote (@bill_e_ghote) April 21, 2018

Ok, full points for recognising that it's a bad analogy, but the premise that an attorney would do this in the first place is extremely unlikely because they would logically stop and think "anyone could walk past and take that". Everyone knows this no matter how technically inclined they are and again, we all learn from a very young age that once you can physically reach out and grab something, you can take it. I know that sounds childishly simplistic, but that's because it is! You can't in any way compare this to an improperly configured webserver.

The whole basis of IRL definitions of public versus private simply don't translate and there are many, many examples of how analogies like this just don't stack up:

Even if it isn’t intended to be public it is. If you post private information to a public notice board with a big banner across the top that says DO NOT READ, it’s still publicly posted.

— dragosr (@dragosr) April 21, 2018

When there's a sign that says "Keep out - private property", that means precisely what it sounds like and if you ignore it - because it's still publicly accessible - undesirable consequences may ensue. But we don't do that on the internet, we use technical controls instead so it's more like putting a security fence around the property... except that's another bad IRL analogy because chain wire works totally differently to digital controls.

It even got to the point where people were arguing about which analogy was best!

Door methaphor seems unadapted. Someone started reading books sequentially at the library instead of using the index and managed to read books that the librarian didn't realize were here. Hardly law enforcement material...

— Julien Roncaglia ? (@virtualblackfox) April 21, 2018

And that one doesn't make any sense either because once you walk through the library door, you expect to be able to read the books on the shelf, that's how libraries work! You're not making GET requests in there, you're picking up real things.

Look - I get it - people are simply trying to explain things in relatable terms and I certainly don't want to criticise them for that intent. However, at best these analogies downplay or overstate the significance of the situation and at the worst, they completely misrepresent reality. So, let's dismiss with the analogies and draw things back to the original topic: if you're in support of enumeration being permissible per the 3 examples I gave in that post, would you do it yourself? Would you pull down hundreds of thousands of records containing other people's data "just because it was there"? And if you did, would you be happy to do so from your own IP address? Would you tell your kids it's ok to do this? Regardless of whether people argue it's legal versus illegal or moral versus immoral, anyone paying attention knows the consequences that may befall you if you go down this path, even if they fundamentally disagree. After all, you wouldn't enumerate a car, would you?