I've been thinking a lot about the relevance of formal education such as university degrees for those of us working in tech lately. Not just degrees, but various other forms of certifications so for the sake of simplicity, let's bundle it all up into "qualifications":

qualification

/ˌkwɒlɪfɪˈkeɪʃ(ə)n/Noun: a pass of an examination or an official completion of a course, especially one conferring status as a recognized practitioner of a profession or activity.

This post has actually been in the works for a while, but there were 2 catalysts for finally writing it, both of which occurred very recently and both of which I felt would make worthy contributions to the narrative. But first, let me start with my own story and then my father's because they both add important context.

My Personal Journey

My original thinking was that I'd be a pilot, just like dad. It was glamorous (at least it was for me as a kid in the 80's) and was the only job I really knew because most of our family friends were from the airline industry. Other than my grandfather who was a farmer, I didn't have much more insight into what adults did and milking cows certainly wasn't my thing.

As I grew up, my aeronautical aspirations began to fade. I found computers which, like it is for most kids, began with me toiling away with a PC at home. I would have been about 11 or 12 when my family first bought one so it was all the stuff kids of that era did, namely playing (and cracking) games. A half dozen years later when it came time to think about an actual career, planes were totally off the radar and I was well and truly hooked on technology. I was living in Singapore for the last couple of years of high school around the early to mid-90's and that was an absolute tech haven with cheap, cutting edge PCs, software and even job opportunities. As a 16-year-old, I was able to work in a satellite systems engineering company part time doing hardware maintenance on PCs whilst also tutoring other expatriates on how these newfangled things worked. It was basic stuff - how to use Microsoft Word or make Encarta run - but it was the beginning of real-world experience.

As school was wrapping up, I started thinking about university because that's just what you did back then. So, I came back to Australia and started a computer science degree and with that came my first exposure to the internet (this was now '95). I'd been toying with bulletin board systems whilst back in Singapore but this was something else altogether - and it was awesome! I desperately wanted to start building for the web but there was absolutely nothing in the way of education available at uni. Over the coming years I'd do COBOL and relational database design but that was the closest I ever got to practical knowledge about how to build software for the internet. In amongst all that, I was doing discrete mathematics and chemistry, both of which I hated yet was forced to participate in "because it's a science degree" (the former I actually did very well at, the latter very badly at). It was driving me nuts - I couldn't learn what I was passionate about and I was wasting my time on things that in my view then (and even now), were completely useless.

So in that first year of uni, I bought a book that I still have today:

And that was the beginning of my web development career. Soon after, I was building websites for people in my spare time. A while after that I had an opportunity to actually build a pretty serious web application for very good money, but it required a larger time commitment so I dropped the uni back to part time. Not too much later, the real-world opportunities to build software were growing day by day. Yet even two and a half years after beginning the degree, I still had zero opportunity to formally learn anything remotely related to web development - we were now all the way up to Internet Explorer 4 and still there was absolutely nothing useful I could study at uni! So I dropped out. And I've never looked back. Not once.

When Qualifications Matter

I always remember dad studying incessantly; there were constant checks on his theoretical knowledge, flying ability and of course, his health (mostly I remember mum telling my brother and I to be quiet so we didn't break dad's concentration). There was a huge amount of formal structure around the assessment of his professional capabilities and really, that seems quite reasonable: he was flying jets around with hundreds of people sitting on board, their lives literally in his hands.

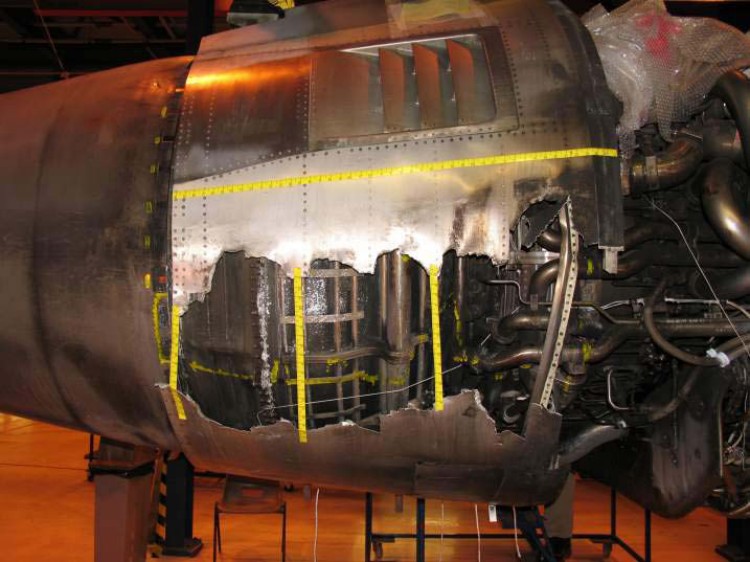

Towards the end of his flying career, he was taking off out of the mountainous Kagoshima airport in Japan when a number of turbine blades on the starboard jet of his 767 exploded from the outboard side of the engine. He took control from the first officer and flew the plane back to the airport on one engine whilst the other one spewed flames, eventually setting the grass on fire once safely back on the ground.

He had to make life and death style decisions the likes of which required extensive training and qualifications. There is no "Landing a Burning Airliner for Dummies" book, you just don't pick this sort of stuff up through practical experience alone.

In so many ways, this is a polar opposite story to my own but it sets the scene for what I want to talk about next. I mentioned two catalysts for finally writing this post, let's start with the first one:

The Equifax CSO's Music Degree

A couple of weeks ago, a story hit the news about the Equifax CSO Susan Mauldin having a music degree. The innuendo was that she was unqualified; how on earth could she hold a C-suite executive position managing the cybers whilst only having studied music?!

I shared the story via a tweet and added a quick bit of context along the lines of "I hope there's more to it than that" which in my mind, meant "I hope there's more to her professional experience that would qualify her for the role than simply having studied something entirely unrelated a long time ago". Unfortunately, I didn't make that sentiment clear enough and as the internet is prone to do, it got angry thinking that I was agreeing with what the story's headline was implying. Clearly, given my own lack of formal qualifications, that was not my intention.

Let's break this situation into two separate but important issues and I want to start with this tweet from the grugq:

It was people without college degrees in infosec that invented the shit they teach in college infosec courses.

— the grugq (@thegrugq) September 16, 2017

This speaks precisely to the point about the value of competency over qualifications. Technology is an industry in which people have done wonderful things without such qualifications. World-changing things, in some cases; Bill Gates dropped out of college. Steve Jobs dropped out of college. Mark Zuckerberg dropped out of college.. Now I'm by no means advocating that if you're presently studying you should immediately drop out and become successful, rather I'm acknowledging that there is clearly more to one's competency and success than a formal qualification alone. I'll come back to that again later on.

The second important issue as it relates to Equifax is that under Susan's watch, something went very badly wrong. Actually, many things went very badly wrong ranging from the breach itself that originally hit the press to the debacle with the search site they stood up afterwards to the subsequent discovery of an earlier breach (and we're only just scratching the surface here). Her subsequent removal from the company ("retirement" in this instance appears to be a term of convenience) and then her apparent scrubbing (or hiding) of her LinkedIn profile is not a good look and it's no wonder that people then probed into her background and started asking questions about her competency.

I have no idea how much of the Equifax debacle was directly Susan's fault. I also have no idea what constraints she was operating under (i.e. tight budgets she fought against) nor how she conducted herself in her role in terms of her professionalism. But I do know that she held multiple infosec roles before her eventual departure from Equifax and that her music degree was gained decades earlier. It might make for easy press-fodder, but her tertiary education is not the issue we should be focusing on here. Clearly there were issues, but a degree in something non-infosec different is not one of them.

Pluralsight

The other catalyst for writing this came as I attend Pluralsight Live last week.

I was watching the presentations around how much content was now in the library, how many hours had been viewed and how it was changing people's lives. Now look, an event like this is always going to be a bit "ra-ra" in terms of talking about how awesome things are, but underpinning all the hype were some fantastic truths about how people were learning technical skills that have made a tangible difference to their lives. Real world, modern and immediately applicable skills that people can use to convert time and expertise into a professional living.

People such as my lovely friend Karoline Klever in Norway who used Pluralsight during her maternity leave to actually progress her career during that period. It's a couple of years old now, but I love this profile on her:

Or my friend John Opdenakker in Belgium who used the CEH content I worked on to pass his Certified Ethical Hacker exam. In John's case, he did actually achieve a professional qualification and I'll come back to CEH a little later on too.

I love that Pluralsight gives people like Karoline and John these opportunities. I love that it's affordable (personal subscriptions start at $29/m), I love that it's self-paced and I love that it's available to anyone anywhere in the world regardless of their access to traditional education. And I love that I've been able to play a part in that.

It's 20 years now since I left university and frankly, if I had have had access to Pluralsight then I doubt I would have lasted more than 6 months in the degree. I'm sure universities have progressed since the mid-90's in terms of how current their content is, but I'm equally sure that they rarely have material taught by industry experts who are absolutely at the forefront of their field and are still actively using the technology in a professional capacity.

Opportunity Costs

What really got me whilst still at uni was the opportunity cost; every moment I was sat in a classroom studying the periodic table for that pointless chemistry course, I wasn't learning something that was genuinely useful. I wasn't building anything and I wasn't gaining any practical experience. All of these things grated on me enormously and it felt like a constant weight.

The other cost I was rapidly racking up with the cost of studying the degree. I can't even remember exactly how much debt I built up during the time I was there (in Australia, we have HECS which is effectively a government subsidised loan), but because I found work early on (and inevitably also because I didn't finish the degree), I paid it down pretty quickly. Most people aren't that fortunate.

Through a quick bit of searching around, I found a piece from last week that suggests a science bachelor's degree in Australia will set you back up to A$43,632 per year which is a massive cost over a typical 3 year degree (that'd run you over US$100k in total for international readers). That figure seems to be pretty consistent with other sources such as this Quora answer from last year.

Edit: A few people have pointed out that there are government subsidies available which significantly reduce the cost of tertiary education.

Now none of this is to say that those degrees aren't worth it and I'll come back to that in more detail in a moment, rather it's to say that the opportunity cost is 3 years and a hundred-something grand; what else could you do with that? How would that change your long-term prospects as opposed to doing the degree? At the very least, it warrants careful consideration.

The Perception of Tertiary Qualification Value

Whilst I've tried to be a bit generic about qualifications in general rather than university or college degrees specifically (and I know I've started to drift this way anyway), let me talk a bit about those in particular for a moment.

In thinking back to my own career, one of the things I remember thinking about as it related to my incomplete degree was that if an organisation rejected me on that basis alone, that wasn't the right place for me. I mean if I went for a job and they said "wow, you've got these years of experience and done awesome things but sorry, policy dictates that you need a degree" then frankly, I wouldn't have wanted to work in that environment. I just couldn't bring myself to be surrounded by people with that mentality.

Anecdotally, there seem to be fewer and fewer organisations expecting a tertiary qualification for technology roles. For example, in the wake of the Equifax situation, Laura Bell from SafeStack.io made the following clear:

We are declaring that we do not require a traditional tertiary qualification for a range of skills-based roles within our company.

She went on to clarify that they've never required a tertiary qualification and that they never will.

One of the things that I myself found during my corporate life was that I simply couldn't correlate formal qualifications with competency. I'd interview people - probably hundreds of them over the years - and naturally, a qualification such as a university degree is one of the first things you'd see on the CV. But in no way whatsoever could I see the value of that represented in any of the technical competency tests we'd do. In fact, difficulty in establishing candidate competency was what led me to write my first ever blog post on why online identities are smart career moves. In that post, I lamented how hard it was to find people with even basic technical knowledge:

The number of times I've interviewed people and they struggled with the most fundamental of questions is staggering. Granted, recruitment agencies have a lot of blame to share but at the end of the day if you're calling yourself a senior .NET developer and can't even write code to declare a nullable type or instantiate a generic collection, you've got issues.

But hey, they had a degree so the recruitment agency sent them through! The very point of that blog post was that you need way more than a CV to actually demonstrate your competence.

(Fun fact: in that first ever blog post I said "I don’t necessarily mean to try and achieve semi celebrity status like Scott Guthrie or Joel Spolsky". In reading it again now, I just realised the 3 of us delivered keynotes from the same stage at Pluralsight Live last week which I reckon is pretty cool!)

And this is really the heart of the problem: a qualification is not experience. A qualification is evidence you've passed a test. The difference between a qualification alone and experience in the real world is, well, this sums it up beautifully:

When you lied on your CV about having previous sheepdog experience. pic.twitter.com/fecGfhE9YD

— Paul Bronks (@BoringEnormous) September 25, 2017

And now that I've said all that, qualifications can still be enormously useful in the tech industry so let's look at where they make sense.

So Are Formal Qualifications Actually Worth It?

There's an easy answer albeit one that can be hard to arrive it: formal qualifications are worth it when they mean something to other people. For example, there are still organisations that expect to see a degree if you want a job there, albeit not the ones I would want to work for! I obviously don't agree with that prerequisite for tech jobs, but if it's a company (or industry) you genuinely want to work with then tertiary qualifications may be very important to you. It's not that different to how it was for dad flying jets - you don't get to do that unless you can pass tests and have papers to prove it.

The same can be said about certifications. Last year I wrote about careers in security and touched on the Certified Ethical Hacker series I'd contributed to building out on Pluralsight. In there, I referenced the DoD's Information Assurance Workforce Improvement Program and the CEH prerequisite:

The United States of America Department of Defense issued Directive 8570 in 2004 to mandate baseline certifications for all Information Assurance “IA” positions. In February of 2010, this directive was enhanced to include the Certified Ethical Hacker across the Computer Network Defense Categories “CND”.

Clearly, if you want to work for the DoD then a CEH cert (or a number of other certs they recognise) is important. I actually copped some criticism from a few folks for not having sat the CEH exam myself after writing the (predominantly) web security components of it but for me it's easy - the cert wouldn't change anything for me in any tangible fashion so I haven't bothered with it. It's that simple.

Obviously, there are other industries where formal qualifications are far more a necessity than the tech industry and dad's case is one great example. Same again for a profession like medicine; as with aviation, it's heavily regulated because if you screw up, people die. You screw up in my profession and the CSS is a bit wonky in Internet Explorer! Indeed, that's also been a criticism of the tech industry in that anyone can jump up and start working in it with next to no knowledge. Heck, I'm making a career out of folks getting that wrong all the time in security! Of course, there are systems that must operate within regulatory guidelines such as PCI and HIPAA, but that's not quite the same as demanding specific qualifications from the practitioners building those systems.

On the tertiary education side of things, I'm actually for attending university after secondary school for folks that are trying to find their way in the world. A very positive attribute of studying for a degree is that it's a commitment that's much harder to break than, say, simply stopping a Pluralsight course. It helps you learn aspects of technology you may or may not like and it exposes you directly to people that can expand your horizons. Many people need that structure.

But ultimately, all of this is merely a means to an end in that it helps you along that journey to a successful career. If formal qualifications are the thing that does that for you then awesome - that's a win. But it's one path and whereas in times gone by it was considered the way into a professional career, clearly that's changing and the decline in students starting IT degrees is evidence of that.

The industry has clearly changed a lot over the last couple of decades. The monolithic approach to study which was "make a large financial commitment over many years" is now complimented with the microservices of education: break knowledge acquisition down into smaller decoupled atomic units focusing on discrete topics, Pluralsight style, if you will. But the best thing of all is that now you can choose and hey, maybe that means you do both; study for a degree and compliment that with online learning or additional certifications. Man, I wish I had that choice 20 years ago!

Summary

One of my most infuriating post-dropout moments came some years later when I called up the uni to inquire about what might be involved in finishing the degree. "Oh no", the lady on the line explained, "all your credits have expired so you'd have to start again". Wait - so if I'd finished the degree would the knowledge I'd earned still be considered null and void by the uni? To which she replied "No, you'd still have the degree". That was a real penny-drop moment for me: study alone can be deemed null and void in the future but experience, well, nobody can take that away from you.

Lastly, I thought I'd pump out a quick survey yesterday just to get a sense of where people's backgrounds lie:

I'm writing a blog on qualifications in tech jobs and I'm curious: if you're in IT / programming / security, what's your background?

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) September 27, 2017

The poll result didn't surprise me, but the replies to it are really interesting. As you'd expect, there's lots of different backgrounds but the one piece of feedback that resonated consistently was how important experience is. It's like it's the great leveller in an industry that's heavily biased towards what you've done rather than the papers you hold. Regardless of how you've arrived in technology, I love that there are so many different paths here and frankly, that makes it all the more interesting.