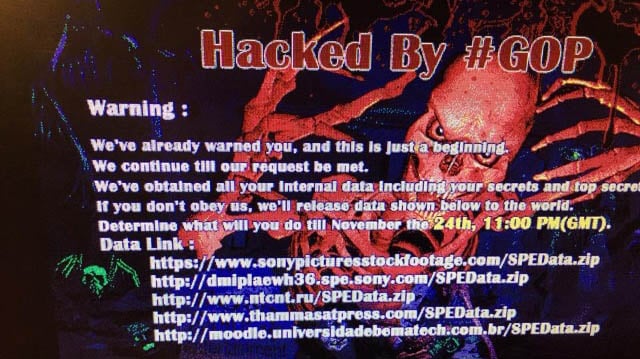

This was pretty big news 18 months ago:

It was what greeted Sony Pictures employees when they turned up to the office and switched on their machines. Machines infected with malware was one thing - a very bad thing at that - but it got much, much worse for Sony.

In all, we saw about 40GB of company data walk out the proverbial door and it included everything from employee credentials to unreleased films to somewhere in the order of 170,000 corporate emails. It was all bad news, but those emails in particular made things especially awkward on the company because it involved such embarrassing exchanges as execs making racist comments about Obama. (Side note: think just for one moment if there's anything in any email you've ever sent - possibly even 20 years ago - which would damage your reputation. Yeah, it's a scary thought...)

But here's the point I'm driving at and why I've kicked off the intro to my new course with a Sony story: the attackers were in Sony's network for more than a year before being discovered. That's astounding not just because a year is a hell of a long time, but because it makes you stop for a moment and think "I wonder how many other networks have malicious actors wandering around them right now. I wonder if my network does?!"

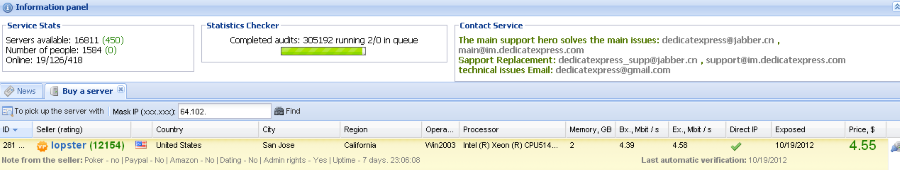

A few years back, Brian Krebs wrote about a service selling access to fortune 500 firms. By all accounts it was a fairly well put together service too. You simply browsed through a rather friendly user interface, picked the organisation you'd like access to and then bought yourself some RDP time. It looked like this:

That seems like a pretty good deal actually - $4.55 for access to a Windows Server box within Cisco! Times gone by, there was this mindset that the network perimeter of an organisation was holy and that anything within it could be trusted. But just as with that horse incident in the city bearing my name a few thousand years back, the perimeter is not sacred and indeed there can be some rather nasty stuff within your walls.

Getting back to the course for a moment, this is now the 7th course I've done in Pluralsight's Ethical Hacking series and as with the other 6, whilst it covers bits from the CEH syllabus, it's a course that can still stand on its own. I suspect everyone reading this already has an understanding of firewalls (although perhaps concepts such as bastion hosts and circuit-level gateways will be new), so I won't dwell on those here. Likewise with intrusion detection systems, whilst a little less familiar to many than firewalls, as a concept they're likely not completely foreign. Honeypots, however, are worth touching on here.

In the course I talk about various honeypot architectures and the role they play within organisations. The one that particularly excites me though is this little guy:

This is a Canary. Obviously. More specifically, it's a turnkey device made by the folks at Thinkst in South Africa and it's quite literally called a Canary. You're probably aware of "the canary in the coal mine" saying, that is the canary was the little fella that would get gassed before the miners did and when he dropped off his perch, they knew it was time to make haste. Canaries in coal mines have become analogous with early warning systems and that's precisely what a honeypot is there for.

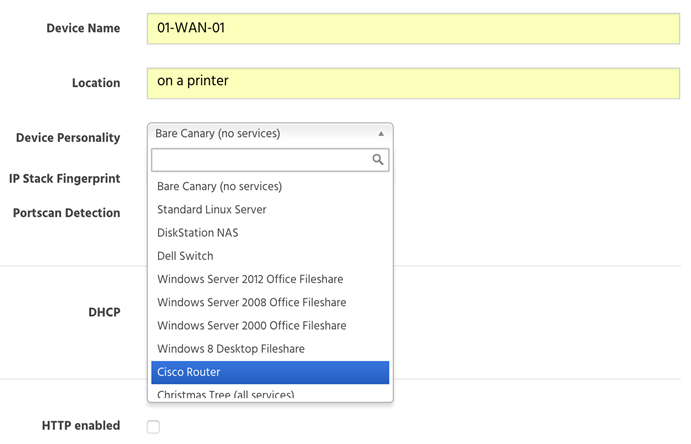

Now imagine that you've got a bunch of these little device and you plug them into the ethernet at work. You then remote into them and set them up like so:

What you're actually doing here is deciding what sort of device you'd like the Canary to emulate. Chuck one in as a Windows Server with a file share, another in as a Dell switch and perhaps make another one appear like a Synology DiskStation NAS. And then you forget about them... unless one of them starts chirping. As soon as someone attempts to, say, pull files off the NAS, the admin gets an alert. A honeypot is a device that serves no normal functional purpose so as soon as someone connects to it (i.e. an adversary probing for devices on the network), alarms start going off.

The whole premise of what you're doing here is putting early warning canaries in your proverbial coal mine. Think back to that Sony Pictures incident for a moment; a honeypot isn't going to stop attackers getting in (that's what firewalls and IDS are for), but they're going to let you know early if they do. If Sony had a handful of Canaries connected to the network (or any other honeypot implementation, for that matter), it almost certainly wouldn't have been a year before the attack was discovered and the damage could have been significantly less.

Honeypots are a complementary technology to IDS and firewalls and certainly there are many others beyond Canary that I touch on in the course as well. Strictly speaking, the course is titled Ethical Hacking: Evading IDS, Firewalls, and Honeypots but it's a lot more about "here's how these technologies function" than it is about evasion (in fact evasion of good honeypots is extremely difficult).

I've got one more course to go in this series and that's one on cloud security that I'm writing now. Until then, this is the latest one in the series and it's available on Pluralsight right now. Enjoy!