When news came through recently about the Bondi Westfield shopping centre’s new “Find my car” feature, the security and privacy implications almost jumped off the page:

“Wait – so you mean all I do is enter a number plate – any number plate – and I get back all this info about other cars parked in the centre? Whoa.”

If that statement sounds a bit liberal, read on and you’ll see just how much information Westfield is intentionally disclosing to the public.

Intended use

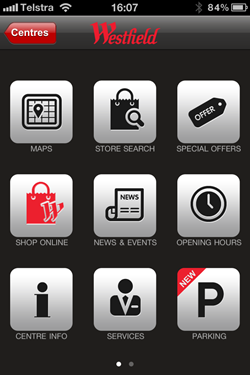

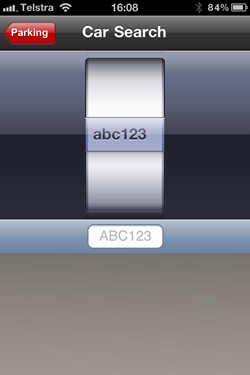

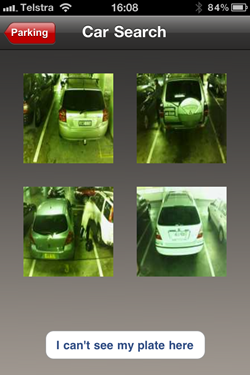

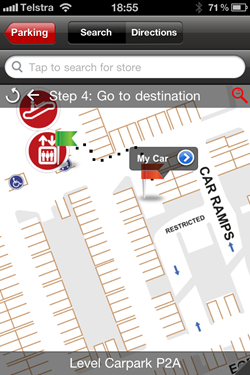

Let’s begin with how the app looks to the end user. This all starts out life as the Westfield malls app in the iTunes app store and for some time now, it’s been able to help you find stores in the centre. As of recently though, it has a “Parking” feature which allows you to enter a number plate and get back a series of images then receive directions on how to navigate to the one which appears to be your vehicle. Perhaps Westfield drew inspiration from Seinfeld’s The Parking Garage on this one! Here’s how it all ties together:

To the casual user of the application, the number plates – and this is what I’m really talking about when I say “privacy” – appear to be indiscernible. Certainly it’s not clear from the images above but it’s also not clear after screen grabbing and expanding it:

The number plate is actually AWC11A, but we’ll get back to that.

Anyway, this is all made possible by using the Park Assist technology which puts the little guy in the image below on the roof between each park so they can both notify customers of vacant spots and snap pictures of them once they park:

The interesting bit though is that the implementation of this app readily exposes some fairly serious, rather extensive data that many people would probably be concerned about. And it doesn’t have to.

Under the covers

The way these smart phone apps tend to work is that when they have a dependency on external data retrieved from the internet, is they communicate backwards and forwards via services which travel over the same protocol as most of your other internet traffic – HTTP. Very often these services contain all sorts of information with only a small subset actually being exposed to the user via the application consuming the service. In Westfield’s case it was fair to assume that this service would contain some information about the vehicles matching the number plate search and what their location is.

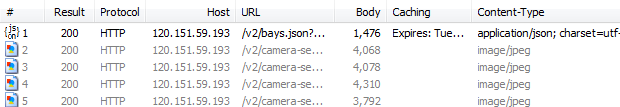

Using a free tool like Fiddler and allowing it to act as an HTTP gateway for the iPhone, it’s easy to interpret and inspect the contents of communication between the app and the server it’s talking to. When I did this for the Westfield app, here’s what I found:

What we’re seeing here is a total of five requests made to Westfield’s server: The first one returns a JSON response which contains the data explaining the location of cars matching the search. The next four requests are for images which are pictures of the cars returned by the search. Here’s what we get:

Apart from the slight difference in aspect ratio, this is exactly what we saw in the original app so no surprises yet. But here’s where it gets really interesting – let’s examine that JSON response. Firstly, it’s a GET request to the following address:

http://120.151.59.193/v2/bays.json?visit.plate.text=abc123~0.3&is_occupied=true&limit=4&order=-similarityOne of the nice things about a RESTful service like this is the ability to easily pass parameters in the request. In the URL above, we can see four parameters:

- The number plate we’re searching for appended with “~0.3”

- An “is_occupied” value set to “true”

- A “limit” set to “4”

- An “order” set to “-similarity”

Now when we look at the response body, we see the following:

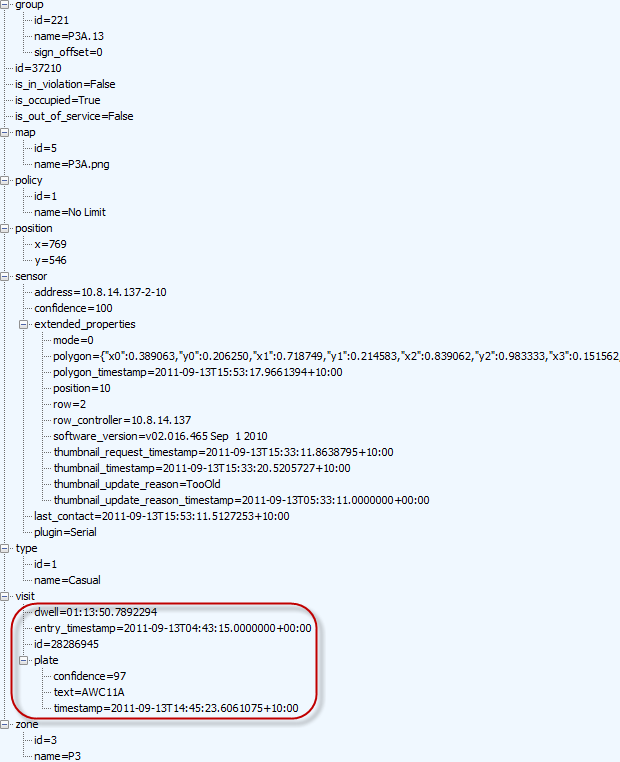

What this is telling us is that the JSON response contains four collections of data. Let’s expand that first one and see what’s inside:

This is a fair bit of data. Actually it’s a lot of data and it’s being sent down to your phone every time you try to locate a car. Remember, all the app needs to do is show us an image of what may be our car. But the really worrying bit is what’s inside the “visit” node; Westfield is storing and making publicly accessible the time of entry and the number plate (see the “text” field) of what appears to be every single vehicle in the centre. What’s more, it’s available as a nice little service easily consumable by anyone with the knowhow to build some basic software.

But this is only four results, right? Actually, it’s worse than that. A lot worse. That URL for the service endpoint we looked at earlier contains a number of parameters – filters, if you like – and removing these readily provides the current status of all 2,550 sensors. This includes the number plate of any car currently occupying a space and as you can see, it’s available by design to anyone:

http://120.151.59.193/v2/bays.json

You can freely request that resource over and over as many times as desired and then store the data to your heart’s content. Now that, is a privacy concern.

The impact to privacy

What this means is that anyone with some rudimentary programming knowledge can track the comings and goings of every single vehicle in one of the country’s busiest shopping centres. In an age where we’ve become surrounded by surveillance cameras we expect our movements to be monitored by the likes of centre management or security forces, but not on public display to anyone with an internet connection!

Think about the potential malicious uses if you’re able to write a simple bit of software:

- A stalker receives a notification when their victim enters the car park (and they’ll know exactly where the victim is parked).

- A suspicious husband tracks when his wife arrives and then leaves the car park.

- An aggrieved driver holding a grudge from a nearby road rage incident monitors for the arrival of the other party.

- A car thief with their eye on a particular vehicle could be notified once it is left unattended in the car park.

With Westfield standing up the service in the way they have, this becomes extremely easy. Furthermore, this is just one shopping centre out of dozens of Westfields across the country. If this practice continues, data mining the movements of individual vehicles across shopping centres will be a breeze for anyone with basic programming knowledge. And that’s really the crux of the problem in that this isn’t one of those “Oh no, the big corporation is tracking me” situations, it’s that anyone can track me.

Whilst I’m by no means a strong privacy advocate (I have a fairly open life on display through numerous channels on the web), something about this just doesn’t sit quite right with me. Certainly those people who are strong privacy advocates would object to such a public disclosure of information.

What needs to be done

Putting my “software architect / security hat” back on for a moment, the problem is simply that Westfield is exposing data this application has no need for. The best way to keep a secret is to never have it and this is where they’ve gone wrong.

The parking feature of the app is designed for only one purpose: taking a number plate from the user and returning four possible positions with grainy images of the vehicle. On this basis, every piece of data in the “visit” node in the image earlier on is totally unnecessary, as is the ability to pull back more than four records at a time and as is the ability to do it over and over again as fast as possible. All that is required is the image so that someone can visually verify it’s their car (the number plate need not be clear), and of course information on the location within the centre.

If they were to do this, the privacy risk is dramatically reduced as all you’re left with now as Joe Public is a small bunch of grainy images with indecipherable number plates. The positive feedback of the service explicitly returning the number plate (and degree of confidence in its integrity), is gone. Sure, there’s still a privacy risk in that I can manually open up the app and search for someone’s car then manually ID it, but the potential for automation is gone.

In fact most of the data returned in that service is totally unnecessary. Trimming it back would not only (largely) resolve the privacy problem, it would also reduce the size of the service hence speeding it up for the end user and reducing the bandwidth burden on Westfield. Win-win-win.

Summary

In the process of researching and writing this post I also identified other major vulnerabilities of a rather serious nature. I’ve done the right thing and attempted to notify Westfield of these and won’t publicly disclose them.

The information above, on the other hand, is already public knowledge in so far as people know there is a database containing their cars that is publicly accessible, they just probably don’t know how easy it is to get hold of. But of course by design, this information is intended to be consumed on demand, as frequently as possible and for any vehicle in the car park.

All in all, this just doesn’t seem to be very well thought out on behalf of the developers. In fact on that basis, if Park Assist is behind this and they’ve implemented the same system in other locations, the Bondi situation could just be the tip of the iceberg. In all likelihood, it’s not Westfield’s intent to expose this volume of information in such an easily consumable fashion and hopefully they’ll ask for the software to be revised once they’re aware of the full extent of the situation.

Update 1, 11:10 Sep 14: A couple of hours after posting this, a helpful reader contacted Park Assist directly and they responded promptly by pulling the service altogether (they appear to control the environment). Based on their response, it seems the API into the service should never have been publicly exposed and used by the iPhone app in this fashion. It also appears that in addition to the privacy risk, further security vulnerabilities were identified by other individuals. Whilst I won’t disclose these publicly, I did attempt to contact Westfield directly about the issue. As of now, I’m still to get a response from them.

Update 2, 12:00 Sep 14: I just had a good phone chat with the guy from from Park Assist who provided the response linked to in the previous update. In short, they’re handled this situation very efficiently and have responded with urgency and professionalism. We discussed some general security concepts including how the service could be properly secured for future use and it’s clear they understand precisely what needs to be done. It’s unfortunate for them that the software was configured in this fashion in the first place but certainly they’re doing everything right in their response.