The situation in Minneapolis at the moment (and many other places in the US) following George Floyd's death is, I think it's fair to say, extremely volatile. I wouldn't even know where to begin commentary on that, but what I do have a voice on is data breaches which prompted me to tweet this out earlier today:

I'm seeing a bunch of tweets along the lines of "Anonymous leaked the email addresses and passwords of the Minneapolis police" with links and screen caps of pastes as "evidence". This is almost certainly fake for several reasons:

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) May 31, 2020

I was CC'd into a bunch of threads that were redistributing the alleged email addresses and passwords, most of them referring to a data breach (or "leak") of some kind allegedly perpetrated by "Anonymous". I've now seen several versions of the same set of email addresses and passwords albeit with different attribution up the top of the file. This is one of the more popular ones that links a hack of the MPD website to leaked credentials:

I've got a lot of "allegedly" and air quotes throughout this post because a lot of it is hard to substantiate, but certainly there's a lot of this sort of thing spreading online at the moment:

ANONYMOUS IS BACK AND HAVE ALREADY H@CKED THE MINNEAPOLIS POLICE DEPARTMENT WEBSITEpic.twitter.com/W7AcHyh3gV

— nutella⁷ closed or ia idk | BLM (@pjnkmin) May 31, 2020

Just to be clear: there's not necessarily a direct link between whoever put the video above together and the data now doing the rounds and attribution is tricky once you get a bunch of different people under different accounts and pseudonyms all flying the "Anonymous" banner. What I'm interested in whether the data I referred to earlier is actually from the MPD or, as I speculated, from elsewhere:

Firstly, each of the random addresses I picked out appears in @haveibeenpwned, usually against credential stuffing lists which have email address and plain text pairs. In other words, this is data that's already out there in other breaches, at least the email addresses are.

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) May 31, 2020

So let's dig into it. There are 798 email addresses in the data set but only 689 unique ones. 87 of the email addresses appear multiple times, usually twice, but one of them 7 times over. I'll come back to the passwords associated with that account in a moment, what I will say for now is that it's extremely unusual to see the same email address with multiple different passwords in a legitimate data breach as most systems simply won't let an address register more than once.

Of the 689 unique email addresses, 654 of them are already in Have I Been Pwned. That's a hit rate of 95% which is massively higher than any all-new legitimate breach. If you have a browse through the HIBP Twitter account, you'll see the percentage of previously breached accounts next to each tweet and it's typically in the 60% to 80% range for services based in the US (lower rates for areas of the world that are underrepresented in HIBP, for example Indonesia and Japan).

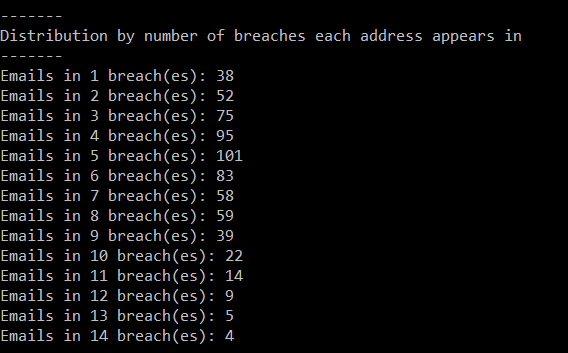

Next up is the distribution of addresses across breaches and I'll share a couple of snippets from one of the tools I use to help attribute data such as this:

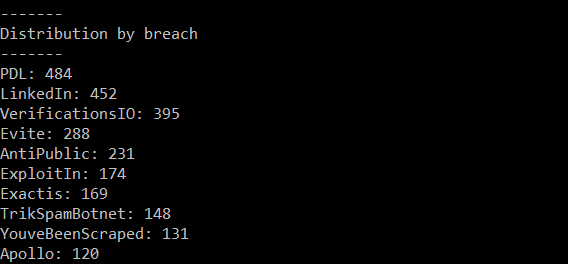

HIBP presently has a ratio of just over 2 breaches per email address in the system. However, what we're seeing here is a very high prevalence of each address appearing not just in 2 breaches, but in an average of 5.5 breaches. In other words, these accounts are breached way more than usual. When we look at which incidents they've been breached in, they're very heavily weighted towards data aggregators, with a couple of notable exceptions:

The People Data Labs breach is in the top spot and it's presently the 4th largest breach in HIBP. Verifications.io is the second largest and Anti Public the 6th largest. The conclusion I draw from this is that a huge amount of the data is coming from aggregated lists known to be in broad circulation. LinkedIn is a bit of an outlier here because whilst the data is in very broad circulation, it's not an aggregation of multiple sets rather a single, discrete breach. Which brings me to next tweet in my thread:

Secondly, the passwords are consistently *woeful* and are often all lowercase, numeric or other patterns that would almost certainly be rejected by any official @minneapolispd system. They're simple passwords most likely cracked from other breaches.

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) May 31, 2020

Two of the passwords in the data clearly tie it back to the LinkedIn breach, one literally being the word "LinkedIn" and the other an all lowercase version of that. It's difficult to imagine someone creating an MPD account with that password. Then again, people do stupid things with passwords (yes, even police officers) so it's possible. What's less likely is that a current day official police department system would allow an all lowercase 8-character password. Not convinced? The following passwords are also present:

- le (yes, with just 2 characters)

- 1603 (which looks like a PIN)

- password

- 123456

As with the LinkedIn passwords, it's possible these are from an official police system, but the likelihood is extremely low. So where could they be from? Let's run them all against Pwned Passwords and see.

There are 795 rows with passwords in the data. That's 3 less than the total number of email addresses as the first 3 lines are addresses only which is also a bit odd. Then again, those first 3 addresses are all @minneapolis.mn.us whereas all the other addresses are @ci.minneapolis.mn.us which feels more like a human error by whoever collated the list rather than the natural output of a dumped database. Of the passwords, 767 of them are distinct (that's a case sensitive distinct) with the dupes being passwords such as:

- goldie (4 occurrences)

- minneapolis (3 occurrences)

- 123456 (2 occurrences)

Frankly, the individual occurrences of those in the data set are quite low, it's the prevalence of the passwords in existing data breaches that's more interesting. Only 86 of the 795 total rows didn't return a hit so in other words, 89% of them have been seen before. Not only seen before, but massively seen before - here's their prevalence in Pwned Passwords:

- 123456 (23,547,453 occurrences)

- qwerty (3,912,816 occurrences)

- password (3,730,471 occurrences)

- abc123 (2,855,057 occurrences)

- password1 (2,413,945 occurrences)

- sunshine (412,385 occurrences)

- shadow (343,769 occurrences)

- linkedin (291,385 occurrences)

- andrew (265,776 occurrences)

- joshua (262,771 occurrences)

- loveme (233,835 occurrences)

- freedom (221,713 occurrences)

- friends (218,341 occurrences)

- summer (214,360 occurrences)

- samantha (211,498 occurrences)

- maggie (211,290 occurrences)

- batman (206,795 occurrences)

- harley (197,503 occurrences)

- jasmine (192,023 occurrences)

- martin (188,772 occurrences)

I want to go back to the email address I mentioned earlier on, the same one that appeared 7 times over. That address appeared once with the alias precisely represented as the password, once with it almost precisely as the password, once with "mickey23", once with "mickey23mikmonkhou", once with "32yekcim" (try reversing it...), once with "mickey2" and once with a "mickey23" prefix followed by a string that created an email address at a college. Why so many times? Because the data has almost certainly been pulled out of existing data breaches in an attempt to falsely fabricate a new one:

What we almost certainly have here is the result of someone selecting every https://t.co/PLqgtO3KjG email address from old breaches or credential stuffing lists and passing it off as something it isn't. There's no evidence whatsoever to suggest this is legitimate.

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) May 31, 2020

These may well be legitimate MPD email addresses and the passwords may well have been used along with those email addresses on other systems, but they almost certainly didn't come from an MPD system and aren't the result of the police department being "hacked".

And why is this happening? Because people are outraged at the situation in Minneapolis and they want this to be true:

Thirdly, this is getting traction because emotions are high; public outrage is driving a desire for this to be true, even if it's not. Hash-tagging it "Anonymous" implies social justice, even if the whole thing is a hoax.

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) May 31, 2020

I want to be really clear about something at this point: events in the US at present are tragic and people should damn well be angry. But anger shouldn't mean throwing logic and reason out the window and I cannot think of a time where fact-checking has ever been more important than now, not just because of the Minneapolis situation, but because so much of what we see online simply can't be trusted. So by all means, be angry, but don't spread disinformation and right now, all signs point to just that - the alleged Minneapolis Police Department "breach" is fake.

One last note: Please keep any commentary on this blog post focused on the data and don't let it descend into politics or emotional responses. This analysis is intended to be data-centric and cut through the FUD that so quickly spreads around highly emotive issues. Disinformation spreads very quickly online, especially so in situations like this where people get "caught up in the excitement".

Looking forward to it. I'm ashamed to admit that I got caught up in the excitement and RT'd the original for like 10 minutes until I saw your original analysis and was like "shit, I'm dumb"

— Antifa Bunny #BlackLivesMatter #ACAB 🐰🎮 (@bunnyladame) June 1, 2020