I see literally millions of compromised records from online systems every week courtesy of maintaining Have I been pwned? (HIBP), in fact I’ve seen well over 200M of them since starting the service just under two years ago. I’ve gotten used to seeing both seriously sensitive personal data (the Adult Friend Finder breach is a good example of that) as well as “copycat” breaches (the same data dumped under different names) and outright made up incidents which have little to no basis on actual fact.

I’m always interested when personal data is leaked online and I’m especially interested when it hits the mainstream headlines in spectacular fashion as its done today:

This was headline news in the Aussie papers and all over the TV news programs as well. It’s not just us though, in fact there’s a mere 8 of us in the “hit list”. The story is making headlines globally right now:

Nothing makes headlines like a combination of ISIS / hackers / terrorism! But how much of a threat is this really? I decided to take a much closer look at the data, let me share what I found.

Understanding the data

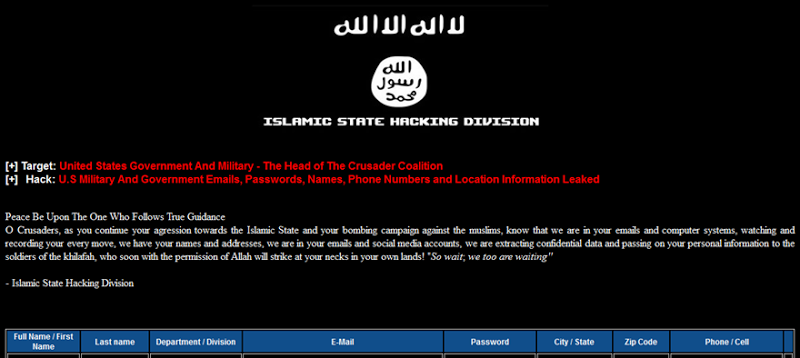

Firstly, here’s what’s in the link that’s presently doing the rounds:

Whilst I’m not going to reproduce any of the data in an identifiable fashion here nor link directly to the sites hosting it (which is often behind Tor hidden services), it’s easily discoverable by anyone with an interest in it. The column headers above are entirely self-explanatory so I won’t dwell on those, but I can talk about the discoverability and likely sources of the data contained in the 1,481 rows in the table. (Note: some of these records are also duplicates with near identical data for the same individual.)

Where could data like this come from?

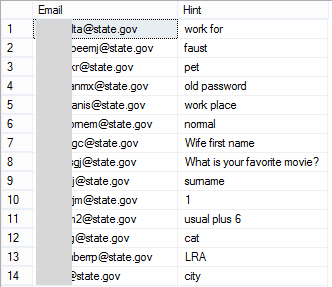

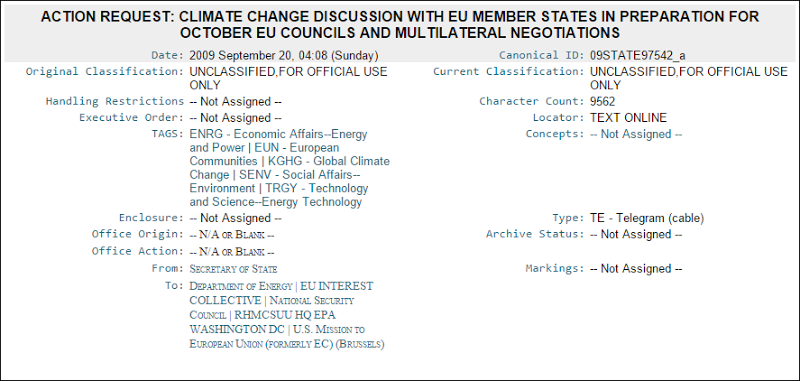

It’s not clear where this list has been compiled from, but let’s be clear about one thing: there are many sources from which attributes in this list can be compiled. For example, in the Adobe breach of 2013 in which 152M records were leaked, there were 257k .gov email addresses. The ISIS list has a lot of state.gov email addresses – Adobe leaked 1,657 of those and they look just like this:

Adobe also leaked password hints so you can begin to quite easily build a profile around people working in the US State Department. Because I have such a large set of data to compare new breaches to, analysing the ISIS set against that was a natural first step (incidentally, there’s a public API that anyone can use to do this). I wrangled up a quick script that pumped out any hits in the data set against existing breaches and let it run. It returned 224 hits with data such as this:

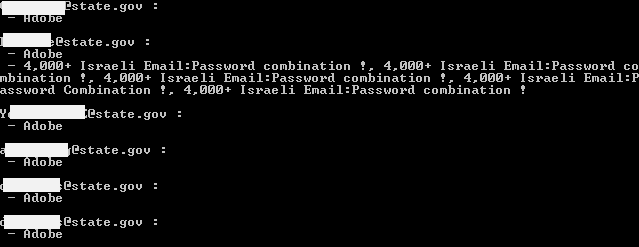

Of course there’s going to be a lot of Adobe hits given the size of the breach, but I also found a number of hits for “pastes”. We often see data leaked via a service like Pastebin where it can easily be anonymously dropped into a public site and shown to the world. For example,

In fact this particular paste included accounts from the ISIS data so you can begin to see a correlation of identity information that’s easily retrievable from the public domain. Take it further and the same identities begin appearing in places like Wikileaks as well:

Incidentally, I matched the individual’s record to here using the advanced hacker tool known as “a Google search” – search for the email address, find more data, build up the profile. It can be that simple.

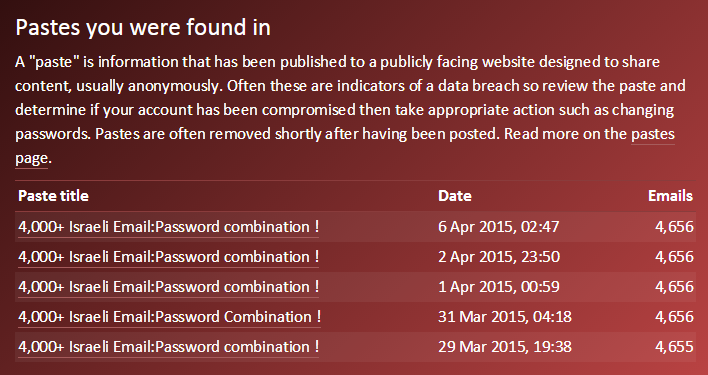

Back on pastes, as an example of how trivially leaked data can often be treated, one of the State Department email addresses was found in these 5 pastes:

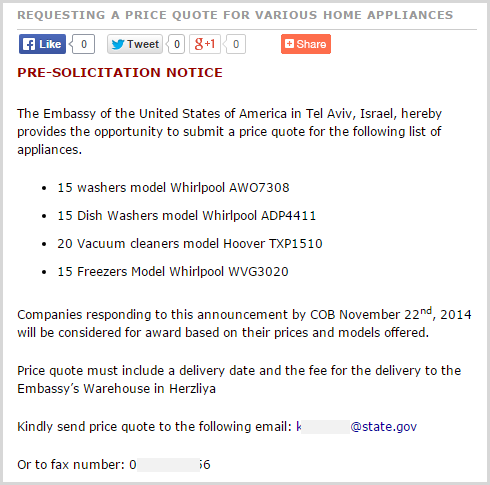

They’re all identical and they’ve simply been reproduced time and time again over a one week period. Each one was removed by Pastebin, but you can easily locate more data about the individual in other locations, for example when they were looking to buy some whitegoods for the American Embassy in Israel:

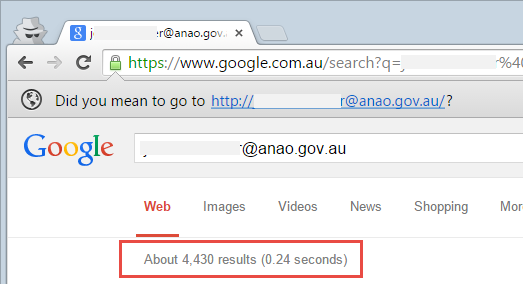

Here’s another good example – one of the Aussie email addresses is @anao.gov.au which is our National Audit Office. Not exactly the government department you’d image to be a massive terrorist target, but let’s look closer at it anyway. A search for the email address quickly reveals thousands of results spread across all sorts of online documents.

They’re not all for the entire email address, many are for the individual’s name itself. This includes photos of the individual:

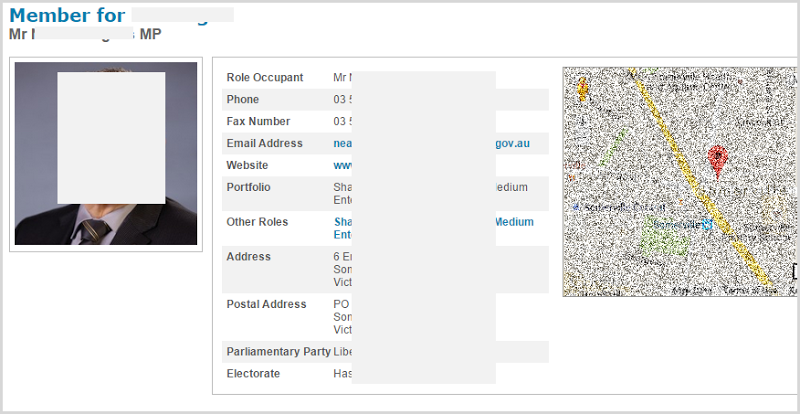

Another case from down here is a state parliamentarian. How would you find his “personal” information? If it was me, I’d start by just getting it off his web page:

It’s trivial to build profile data when it’s spread all over the web anyway. The presence of this data alone does not constitute a single data breach or targeted attack, it could simply be no more than a collection of easily obtainable records for individuals holding (mostly) public service roles.

The individuals are often not in defence or intelligence roles

The message preceding the data in the image earlier on talks about “agression towards the Islamic State and your bombing campaign against the muslims”, but we then have a significant number of addresses from government departments in no way linked to what could be constituted as aggressive roles.

For example:

- @bizlink.nsw.gov.au – Businesslink is a state level service that’s now part of the Department of Family and Community Services who among other things, helps support children who have suffered abuse

- @sesiahs.health.nsw.gov.au – South Eastern Sydney Illawarra Health Service, it helps support the health of the local community

- @abcgroup.com – “ABC Group is a world leader in vertically integrated plastic processing”

In fact the last one isn’t even a government department, yet somehow it makes the list. The reasoning isn’t clear but it doesn’t appear to be by design. It’s more likely that these addresses are a combination of looking for .gov emails regardless of the individuals’ intended roles and they’ve been amalgamated with others caught up in the exercise.

The passwords are of little consequence

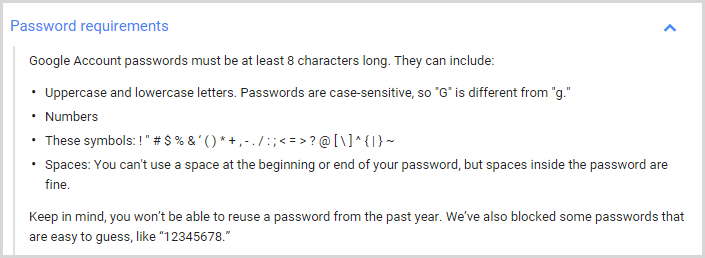

The first thing that stuck out at me with the passwords is that there’s no context; it’s not like the place they were actually used is represented. The second thing is that I can tell you where a significant portion of them weren’t used and that’s on a corporate or government system because many of them are exceptionally weak. For example:

- 171717

- tulasi

- 146

Password rules would put a hard stop to all of these in pretty much any corporate system, let alone the government ones the email addresses of the individuals suggest they use. In fact you couldn’t even use these on many general online sites, for example with Google:

One oddity is an unusual prevalence of passwords conforming to this pattern:

- AD552AF637AB4A56

- 77AF444AA9124B6A

- B42455E325A4EFA6

These are not hashes or any identifiable means of cryptographic storage and the only place they appear in Google searches is within the ISIS data itself. They’re also spread across entirely different email domains so are unlikely to have come from the source system the email is maintained on (i.e. the US State Department).

Duplicate records

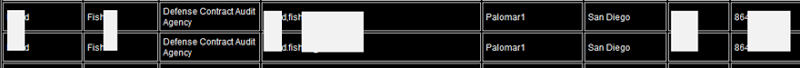

One interesting observation in the data is where duplicates appear – it’s the same individuals with almost identical data bar very minor differences, for example:

The top record has a comma between first and last names, the bottom one has a full stop. It appears as though data from multiple sources exists in a system somewhere and the process that’s dumped it into the format that was then released to the web hasn’t properly de-duped the records. My first reaction on seeing this is that someone is maintaining this data somewhere centrally (which could merely be an Access database on their desktop) and then pumping it out in this format. It’s as if someone has just done a “distinct” query on the data and the subtle differences have artificially bulked up the results.

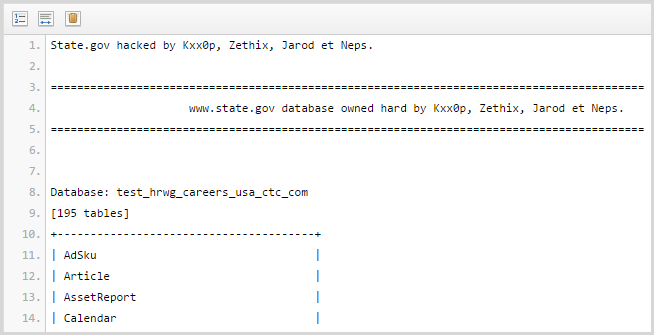

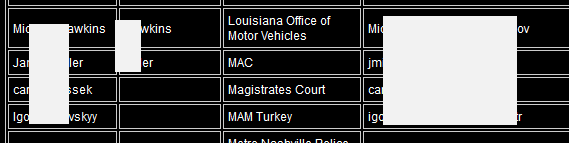

Inconsistent data structures

Another observation that suggests the data is sourced from multiple systems is the inconsistency of the data attributes:

Here we have the first couple of rows with both the last and first names in the first column and the last name only in the second column then the next couple of rows also containing first and last names in the first column but none in the second. Much of the other data has a more predictable structure with first names in the first column and last names in the second.

This is the sort of thing you see when data is aggregated from different locations following different storage practices.

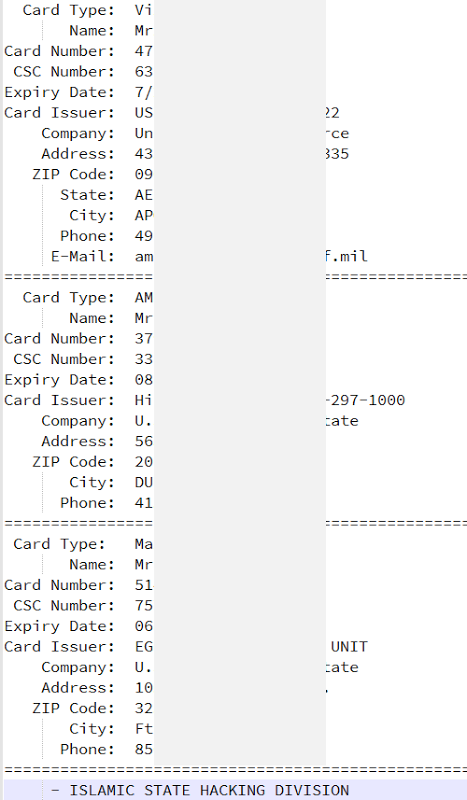

Credit cards

There are 3 credit cards in an image after the tabular data:

There were no obvious hits on these from a cursory search of the web, but keep in mind how many credit cards are breached in attacks on a regular basis. Just last year we had many breaches of millions of cards each from the likes of Staples and Home Depot not to mention the 40 million cards from Target the year before. If you’re in any doubt whatsoever about the prevalence of credit card data on the web, take a quick look at @NeedADebit card on Twitter.

None of this explains where these three records are from or indeed if they’re even legitimate, the point is that a mere three credit cards on a site is very inconclusive information.

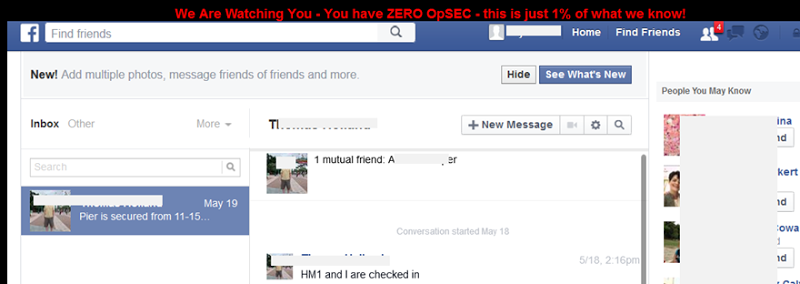

Facebook chats

There are three private Facebook chats similar to this:

The owners of the accounts shown in these images also appear in the tabular data with US Navy and Army email addresses . It’s entirely possible their accounts have been compromised and the screen captures themselves appear legitimate. It may be that these images were obtained from another source (the images of the private chats), but it’s also feasible that their Facebook accounts were indeed compromised. The dates are from Feb and May so some time ago already. However, it’s almost certainly a reflection of poor password practices on behalf of the targets as opposed to the security prowess of the attackers, Facebook runs a pretty tight ship these days and online “hacks” of this nature (almost) always come down to weaknesses on behalf of the user rather than the system.

In short, it’s two compromised accounts on a service that inevitably sees thousands (probably hundreds of thousands) of similar incidents every day.

Conclusions

Keeping in mind that these are all conclusions drawn merely from looking at the leaked list and applying what I’ve observed from experience with previous data dumps, here’s what sticks out at me:

- The data is almost certainly from multiple locations and very unlikely to be from a single data breach

- It appears hastily coupled together with inconsistent data structures and duplicate records

- A number of records have no relationship to military or even government, they appear out of place in the data set

- Many of the passwords are not from any system of significance – they’re too weak

- Most of the data is easily discoverable via either existing data breaches or information intentionally made public

I appreciate how this makes headlines and also that it would concern the individuals who appear on the list. Given their predominantly government roles I’m sure they’re being appropriately supported and guided, but on the surface of it there appears to be nothing sensational about this data other than the context it’s represented in. Even the source of the amalgamated data is unverifiable – it could be someone who does indeed wish harm on the individuals named, it could be a kid in his pyjamas, there’s just not enough information to draw a conclusion either way.