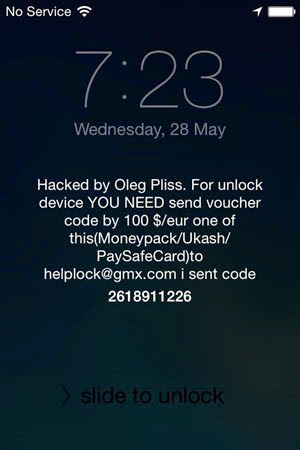

If you’re an Aussie with an iPhone, there’s a chance you’ve been woken up in the middle of the night by this:

Oh boy. What we’re looking at is an iPhone that has been remotely locked by “Oleg Pliss”. What we’re looking at is a modern incarnation of ransomware executed via Apple’s iCloud and impacting devices using the “Find my iPhone” feature. Perplexingly, this is predominantly impacting Aussie iCloud users and to date, there’s no clear reason why, rather we have 23 pages of reported hacks and general speculation on the Apple Support Community website.

I’ve been speaking to a bunch of people about this over the last couple of days about this attack so I thought I’d collate some info on how it works, what we know and what the possible sources of the attack may be

The “Find My iPhone” feature

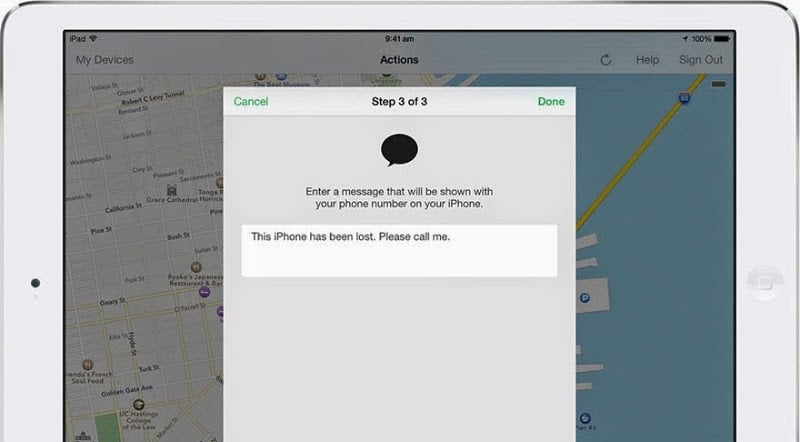

Here’s the promise of the Find My iPhone (or iPad or Mac) service: if you’re like my wife who days after buying her iPhone lost it down the beach somewhere never to be found again, rather than combing through the sand and spending hours desperately searching for it, you can pinpoint it’s position using the Find My iPhone app (obviously on someone else’s phone!). It looks like this:

Here the iPad is running the app (the phone is in “Lost Mode” so you can see where it’s been travelling over the last 24 hours) and the “lost” phone has had a message sent to it asking for the owner to be called (clearly on another number). You can also play a sound (great for those times when you've lost it down the back of the couch) or remotely erase all your data. And finally, if the phone doesn’t already have a PIN on it (you know, the one you should enter each time you turn it on), you can remotely set one.

Per Apple’s advice, here’s how to handle a lost phone:

If your device goes missing, put it in Lost Mode immediately. Enter a four-digit passcode to prevent anyone else from accessing your personal information.

Once you’ve locked it so that nobody else can gain access to it, you should send it a message:

And that’s that. The honest person who finds your phone won’t be able to access your data, will have a nice little message and a means of contacting you and just to be sure they know you’re looking for it, you can ask it to blare out a nice loud noise (yes, this still works when the phone is muted).

If you’re an attacker with access to someone’s iCloud, you can do exactly the same thing which brings us to the present spate of attacks.

How the attacks are being executed

The evidence at the moment suggest that the attacker is simply using the process above to remotely lock peoples’ devices and then demand cash in return for him unlocking the device. (Of course given the victim’s device is now locked, assumedly the attacker would have them use someone else’s machine to send payment.)

Let me walk through the attack from end to end using my primary phone as the attacker (an iPhone 5) and my backup phone (an iPhone 4) can be the victim. The whole thing may well be more sophisticated and automated than this, but here’s how to reproduce the process using the intended function of iCloud and Find My iPhone:

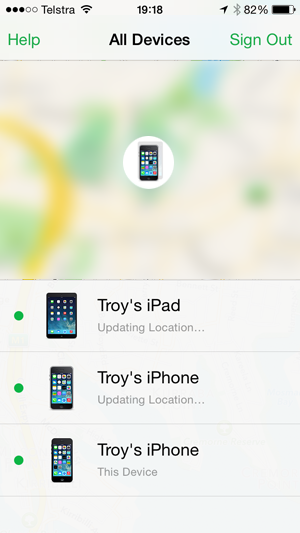

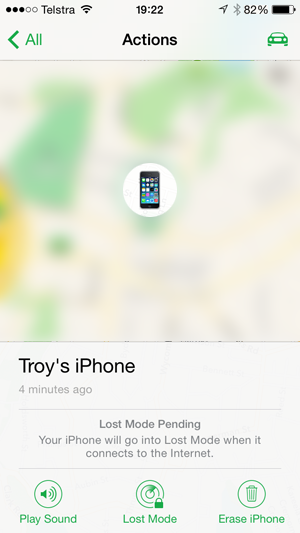

The attacker first compromises the victim’s iCloud account (more on how they might do that in a moment). Once they have access to the account, they fire up Find My iPhone on their own device and log in as the victim. They can now see all of the victim’s devices including where they are physically located (assuming they’re communicative, that is they’re turned on and have an internet connection via wifi or telco):

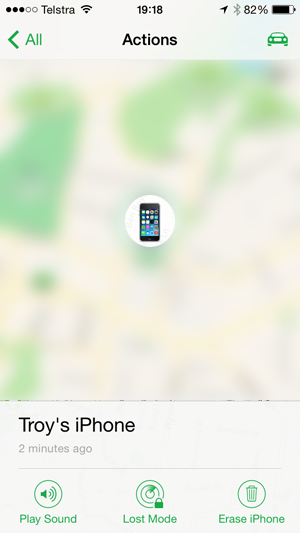

Here we’re seeing my iPad, my primary iPhone (the one that says “This Device) and my test iPhone that will be the “victim” (the one that’s “Updating Location…”). I’ve selected the victim’s device which now gives me as the attacker a number of options:

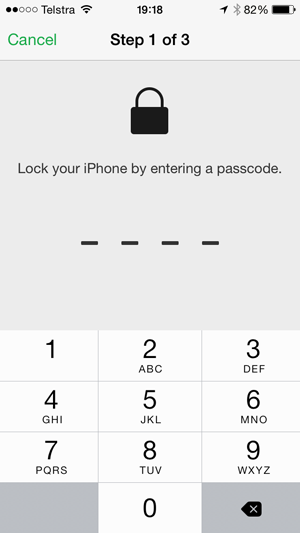

I’ve now put the phone into “Lost Mode” which begins a wizard with a series of steps, firstly confirming that I do indeed want to assume the device has been lost:

Once confirmed, this is where things get nasty for the victim: the attacker can now define a PIN that will lock the phone:

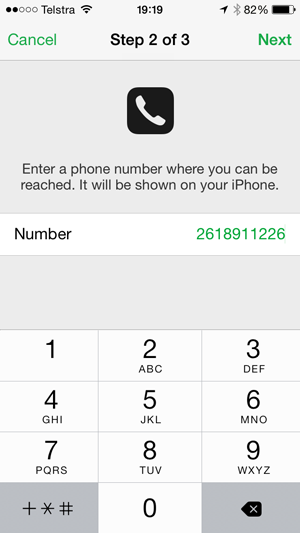

They can also provide a number which will be presented to the person who “finds” the lost phone which of course in this case, is actually the legitimate owner:

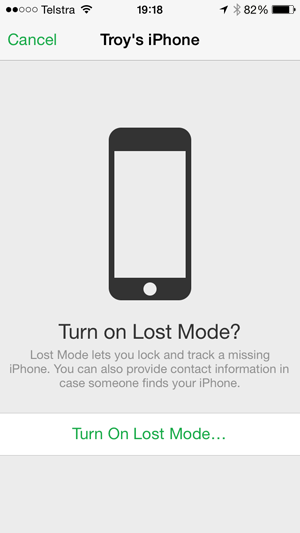

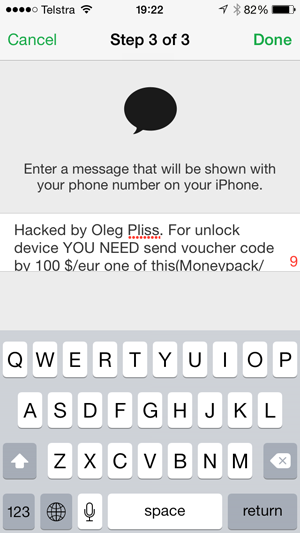

The next step is to enter a message to be displayed and this is the one demanding the ransom:

Once that’s done, iCloud will contact the “lost” phone and lock it with the PIN:

Next, as the hacker I hit the “Play Sound” button and the victim’s phone starts blasting at full volume (again, regardless of if it’s muted or not and regardless of the current volume setting). This is what many victims were reportedly woken up by at all hours of the night.

As for the victim’s phone, it now looks like this:

Any attempt to unlock the phone now requires the PIN that only the attacker has. And that’s it – that’s how the attack is executed.

But of course it all begs the question – how is this attack happening? Isn’t iCloud “secure”? With no hard evidence we can only speculate, but there are some likely suspects.

Password reuse

In a situation like this, the answer which makes the least assumptions is probably the right one and on that basis the attacker is simply logging on with the victim’s username and password. This means of attack makes no assumptions about a direct vulnerability on Apple’s end, rather it recognises the reality that people make very, very bad password choices. Bad password choices include predictable passwords (keyboard patterns, common names, etc.) and of course, reusing the same password across multiple independent services.

But this alone doesn’t explain the sudden spate of attacks against iCloud in the last couple of days, instead there’d need to be some sort of precursor and in the context of password reuse, that would usually be the compromise of another service. Some people have suggested that the eBay attack from last week is just that – the means by which credentials were exposed upon which they were then used to gain access to iCloud accounts using the same username and password. This is unlikely for several reasons.

Firstly, eBay is obviously a global service and if indeed 145 million “active” users were compromised as they’ve said, it’s unlikely we’d see the data then used in attacks against an almost exclusively Australian audience. We have less than 1% of the global internet audience down here so short of the eBay compromise being isolated to an Aussie audience for some reason, this just doesn’t add up.

Secondly, whilst we don’t know the actual details of the cryptographic scheme, eBay has made assertions that the passwords were “encrypted” and shouldn’t be readily retrievable even when breached. Of course we’ve seen a lot of motherhood claims like this from a lot of companies that have turned out to be way too optimistic, but you’d expect eBay of all companies to more likely than not do a good job of this. Yes, they’ve done the arse-covering exercise of asking people to change passwords, but the likelihood of passwords being cracked and floating around in the clear is much lower than what we’re used to seeing.

Thirdly, the breach has never been made public like it was with Adobe and many, many other breaches both before and after them. This is not the common hacktivist pattern of, say, Bell in Canada where the attacker grabs all the passwords in an unencrypted format then posts them all up for public display. It’s not that by a long shot.

No, it’s unlikely eBay but it could be a breach of a local service containing predominantly Australian users. Whilst I’m not aware of any recent attacks that fit that criteria, there’s every chance there’s an as yet undiscovered breach somewhere, certainly that’s a common enough scenario. Mind you, we are seeing international iOS users beginning to be impacted by this breach as well (albeit in what appears to be comparatively small numbers), which is a bit of an exception to that theory, but we may yet find there’s still a commonality in a breach somewhere.

In terms of victims simply having weak passwords that were “brute forced” (i.e. the attacker just keeps trying different ones for a particular user), it’s unlikely Apple’s systems would have facilitated this, at least not by design. Multiple login attempts for a single user are easily detected and fraud protection measures are in place in most services of this nature.

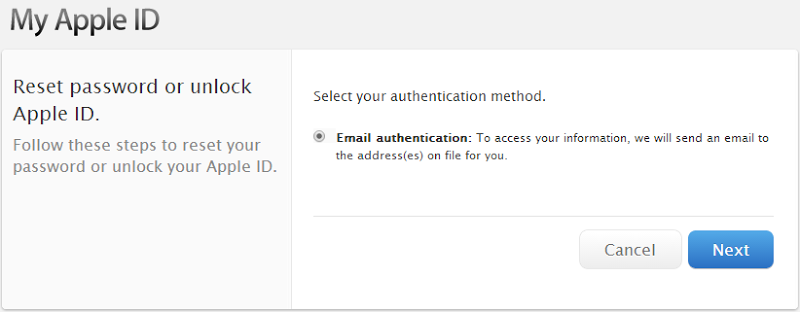

Lost password process exploit

Another possibility is an exploit in the process that follows a “lost” password. Typically this involves an identity verification process and depending on the service, it may take on different forms. For example, in testing a random email address, Apple’s iForgot service offered to authenticate the user via their email:

Clearly the risk here is that if the user’s email has been compromised and again, this could be due to simple password reuse, then this provides the key to unlock the Apple account. I wasn’t able to proceed with this process because my Apple account uses 2 factor authentication (more on that later) and requires a special “recovery key”, but a common part of a lost password process involves both an email and then verification of a “secret question”.

I’ve written about this sort of process before and pointed out that particularly when it comes to secret questions, it’s easy to leave a gaping hole in the security profile. In that post I refer to the precedent of Sarah Palin’s Yahoo! email account being hacked by exploiting the password reset feature simply by the hacker being able to discover her high school and birthdate which are obviously both easily obtainable pieces of information, particularly for a public figure.

Alternatively, there may also be a flaw in Apple’s human support process and certainly we’ve seen that exploited in the past in order to compromise an Apple ID. But that would be a very laborious effort compared to what could potentially be automated in an attack and we’re more likely to see this in a spear phishing style compromise of an account.

While I mention phishing, of course this could all be the result of a very effective phishing attack, but it would have to have been very targeted at the Australian audience to result in the bias that we’re seeing in the victim’s location. Large lists of email addresses are very easily obtainable (there’s 152 million courtesy of Adobe that anyone can go and grab right now) and would be unlikely to see one both so localised and so effective against those of us down here. Not impossible mind you, just not a likely explanation.

Is there a vulnerability in iCloud?

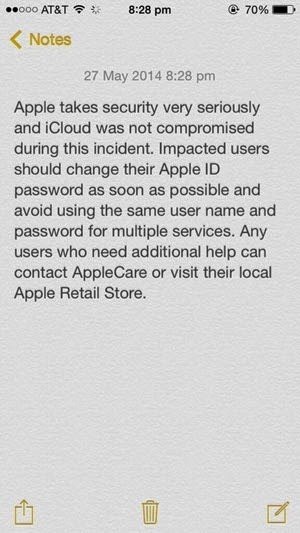

Of course the first thing people assume when they see their locked device is that somehow, Apple is to blame. It must be a vulnerability in iCloud, right? Ben Grubb from the Sydney Morning Herald got this response from them earlier today:

The generic and frankly meaningless “we take security seriously” statement aside, Apple is denying any compromise of iCloud and implying that weak user credentials are to blame. They may well be right, but the response reeks of a canned message with little attempt to actually address the specific concerns of users.

Personally I believe it’s less likely that iCloud has a vulnerability that’s causing this than it is that people simply make bad password choices, but their response is dismissive and does little to reassure their customers. For a company that’s so focussed on the overall user experience of their products, this is an odd response and I would have hoped for more. That said, they’re undoubtedly investigating this behind closed doors and if the attacks mount – particularly globally – at some point they may well be forced to respond in more detail.

Some people have speculated that last week’s news about an iCloud hack is related to this week’s events. This is a very different context – the research Doulci did refers to the ability to unlock phones they have in their hand thus circumventing the controls that are meant to deter theft (i.e. you steal someone’s phone and you won’t be able to do anything with it). This was not about the ability to remotely lock someone else’s phone they had no access to. Maybe there’s a connection somewhere – perhaps they discovered other risks at the same time (one that predominantly impacts Aussies…) – but for now these two incidents seem unrelated.

DNS poisoning

One of the suggestions that has regularly popped up in that original Apply support forum I referred to earlier is a possible “DNS poisoning” due to people using the popular Unblockus service to circumvent geographic controls on foreigners watching US content such as Netflix. The service depends on customers changing their DNS settings or in other words, giving this third part control over the service which resolves names such as apple.com to actual servers on the web.

In a DNS poisoning attack, the hacker would compromise the DNS service such that a request for, say apple.com, would route to a server of the attacker’s choosing. In theory, this would then allow them to access traffic between the victim and the intended service.

This is unlikely for a couple of reasons. For one, the service is used broadly across the globe and Australia is but one of the countries with an audience routing their DNS through Unblockus. Most importantly though, this is the entire premise of encrypted communications on the web using SSL; even when the connection is compromised, the traffic remains secure between the client and the server. Short of a compromise of the certificates Apple uses or a compromise of a certificate authority which lead to the issuing of rogue certificates (DigiNotar is a good example of a precedent), this is highly unlikely.

Is it the Chinese / Russians / NSA?

They’re into everything anyway, right?! We tend to identify three common classes of online attacker:

- Hacktivists: often just kids out for kicks that are opportunistic and not particularly sophisticated

- Career criminals: the most likely scenario here given the attack is clearly financially motivated

- Nation states: the guys in the heading above (among others)

There’s a definite upside to nation states compromising iCloud and I’ll touch on those in the next section, but that upside doesn’t include trying to skim a hundred bucks a pop off victims. Indeed blasting out their presence is the last thing a nation state would want to do and slipping in under the radar is their entire MO so no, it’s almost certainly not these guys.

A ransom is just scratching the surface…

Locking a phone and asking for $100 is a fast grab for cash. Put the victim in a vulnerable position, offer a quick fix costing what for most is an easily obtainable amount of money and that’s it, job done. But access to someone’s iCloud offers much, much more potential than just a small ransom.

For starters, many people back up their devices automatically to iCloud so their entire iPhone and iPad contents are sitting up there in Apple’s cloud. An attacker with control over someone’s iCloud has the ability to restore one of these backups to their own devices which means they get the victim’s photos, videos, documents, iMessages, email stored on the device and basically any conceivable digital asset the victim has on their iPhone or iPad. It’s a very large collection of extremely personal data.

Beyond backups, an attacker also has the ability to silently track the movements of the victim. We saw that earlier on when I reproduced the attack and the Find My iPhone app presented the location of each device on a map. Clearly that creates the potential for a serious invasion of privacy, particularly when you consider that families often have multiple devices under the one iCloud account.

Of course it’s not just iDevices connected to iCloud either and indeed we’ve already seen Macs impacted as well. The reality is that our digital lives are so intrinsically chained together across otherwise independent devices that a breach of a common service like iCloud can have very broad-reaching ramifications. The Epic Hacking of Mat Honan a couple of years ago was a perfect example of the devastation this can cause; not only did the hacker compromise his Apple account (in that instance, via social engineering), he also compromised Mat’s Gmail and ultimately used his Twitter account to start sending out racist tweets. The hacking of an Apple ID can have a very long tail indeed.

Other ransomware attacks

This attack falls into a class we’d often refer to as ransomware, albeit not via malicious software which is how we’ve traditionally seen similar attacks launched. Regardless, the modus operandi is the same – the attacker locks up the victim’s files and won’t release them until a sum of money is paid. Ransomware attacks can be extremely effective in that they’re often not easily circumvented once mounted and indeed previous attacks that have relied on malware have used very effective encryption algorithms to lock up victim’s files.

These attacks often rely on malware like CryptoLocker and indeed they’ve impacted Aussies in the past. A couple of years ago it was a doctor’s surgery on the Gold Coast that got hit with demands of $4k in order to obtain the encryption key and release the victim’s files. This was one of the more high profile incidents, there have been a huge number of others that haven’t hit the headlines.

Clearly, holding digital assets for ransom can be a lucrative business.

Recovering from the attack

I’ll start by deferring to the Aus government’s advice on the Stay Smart Online website – don’t pay the ransom! There are a couple of ways to recover from the attack and Apple outlines them in their Forgot passcode or device disabled knowledge base article. In short, one way around this is to simply restore from a backup via iTunes. Of course that’s dependent on you actually having a backup in iTunes and indeed Apple have regularly promoted backing up to iCloud as a preferable mechanism (remember, this is apparently the “post-PC” era). But even if there is a backup, there’s the question of how recent it is – have you possibly just lost a week of kid photos? A month? A year?

If you were backing up to iCloud then you can always restore from there. Of course that’s also dependent on actually being able to access iCloud in the first place, you know, the place the attacker already controls! If he’s elected to change the password (and so far I’ve not seen a report of that in this recent spate of incidents), then you might be in for a password recovery process assuming they haven’t also compromised your ability to do that. Oh – and of course all this assumes that they haven’t deleted the device backups from iCloud altogether.

It’s a nasty chaining of events and if it all seems a bit too much for some people, there’s always the option of a visit to the local Apple store who should be able to put them back on the right track.

Mitigating the risk: Strong password, PIN and 2 factor authentication

The defences against this threat are nothing new, indeed they’re the very ones that have so long been advocated by so many of us in the security field and they break into three simple steps:

- Use a strong password on the Apple ID: This is online security 101 and any reuse of a password across services is just asking for trouble, particularly when it’s protecting something as valuable as iCloud. Make it unique, make it long, make it random.

- Use a PIN on the device: iPhones and iPads that have a PIN don’t present the attacker with the ability to set their own. That screen earlier on where I remotely locked the device is only presented when it doesn’t already have a PIN so that immediately thwarts this attack. Even if the device is just for the kids, if you connect it to iCloud, put a PIN on it (don’t worry about it making life hard for them, kids have an uncanny ability to access a device protected by nothing more than four numbers).

- Enable 2 factor authentication on the Apple ID: This is another fundamentally good practice and it involves configuring the account such that any attempt to login from a web browser or a different device requires you to verify the login request using “something you have” and not just “something you know” which is the Apple ID password. This puts a dead stop to attacks that abuse credentials and you can read about it on Apple’s FAQ about two-step verification. Just one note on that – there’s a three day lead time to activate it so in the context of this risk, it doesn’t immediately grant you any protection so get the ball rolling now!

Again, these are all just fundamentally good practice that should be in place anyway. If you don’t have all these three boxes checked across all your devices, get them in place as a matter of priority.

Should you stop using iCloud?

I’m going to go with a “no” here with a preference to properly securing your iCloud as opposed to not using it at all and running other risks. Yes, you could avoid using it but then you have to weigh up the risk of losing your phone and not being able to find it again or the risk of not backing up the device then having it lost or corrupted and losing valuable digital assets.

When the aforementioned mitigations are in place, the security provisions offered by iCloud are in my opinion more than sufficient to adequately protect the device when you consider the risks you run without iCloud. That might sound like a very caveated statement and it is: that’s my view for my risk assessment and the value I place on the service, other people may be more wary or less worried about things like backups and the therefore take a different path.

The last thing I’ll say on this topic is that whilst the most likely explanations may be obvious, I’d keep an open mind regarding assumptions on how all these services work. Don’t discount as yet unknown flaws (at least unknown by everyone who isn’t the attacker), and exploits that may well circumvent what we otherwise hold to be truths about how the iCloud service works. We may well yet be surprised by the ingenuity this guy has shown to execute what has arguably been a very impactful attack against Apple device owners.

This still has a way to go before everything plays out and frankly, I doubt that anyone outside Apple and the hacker himself know exactly how this whole thing has been possible (and I’m not even that sure that Apple do). What I do know though is that it only appears to be impacting those who haven’t been able to tick all the usual security boxes and as inconvenient as the whole thing may have been for them, it should be of some reassurance for the rest of us.

Update, June 10: The attackers have now been caught and their means of hijacking iCloud accounts was... phishing. Why it was so targeted at an Australian audience is still not clear.