It’s about assurance. It’s about establishing a degree of trust in a site’s legitimacy that’s sufficient for you to confidently transmit and receive data with the knowledge that it’s reaching its intended destination without being intercepted or manipulated in the process.

Last week I wrote a (slightly) tongue-in-cheek post about the Who’s who of bad password practices. I was critical of a number of sites not implementing SSL as no indication of it was present in the browser. “But wait!” some commenters shouted, “you can still post to HTTPS and the data will be encrypted” they yelled, “stop propagating fear and misunderstanding”, they warned.

I thought carefully about these responses and made a little update at the end of the post but the story of posting data from HTTP to HTTPS is worth more than just a footnote. The real misunderstanding in this story is believing that just because the credentials are encrypted in transit, SSL has been properly implemented. Let’s took a good look at what’s wrong with that belief and why there’s more to SSL than just encryption.

Assumed assurance without positive feedback

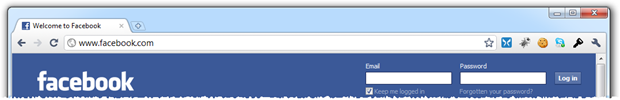

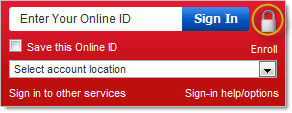

Let’s start with just the encryption piece and take a look at a few familiar sites. Which of the following do you think will protect your credentials over the wire:

Any of them? Actually, all of them implement SSL when transferring your credentials. But of course you had no way of knowing that from the images above, did you? If you’re a bit technical, you could have inspected the source code of the page and seen the form posting to an HTTPS address or you could have watched Fiddler as the request was made and seen the protocol change from HTTP to HTTPS.

The problem is that most people aren’t you. All they have at their disposal in order to judge the relative security of a site is the information their browser gives them via the ubiquitous SSL indicators. Without this, they assume – perhaps because of the profile of these sites – that both the legitimacy of the site and that their credentials are appropriately secured.

Implicit assurance either with or without positive feedback

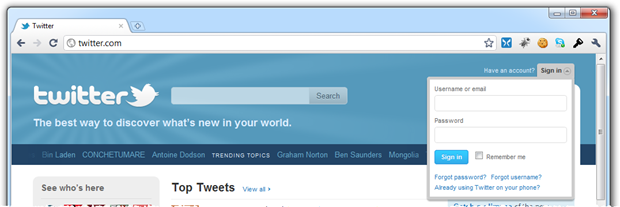

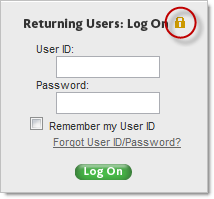

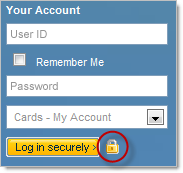

Let’s look at some other sites from a slightly different angle:

The assurance these sites are attempting to create is implicit. They’re saying “Hey, there’s an image of a padlock on our logon form therefore we are secure”. Of course this means nothing of the sort and the ubiquitous padlock image – eerily similar to the one most browsers natively display when the request is made over HTTPS – is nothing more than an attempt to imply legitimacy and security.

The point I want to make here is that without the browser actively making the presence of SSL clearly visible and allowing the certificate to be inspected, these icons mean absolutely nothing. In fact they’re very misleading and create a false sense of security by implying something that they’re simply not, regardless of whether SSL is present.

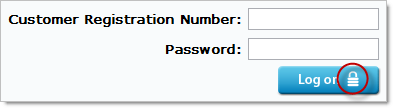

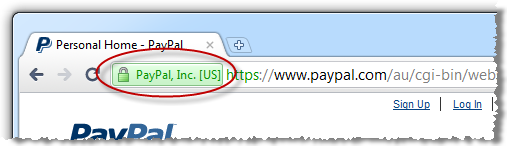

Creating positive feedback and explicit assurance

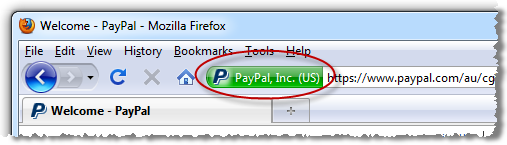

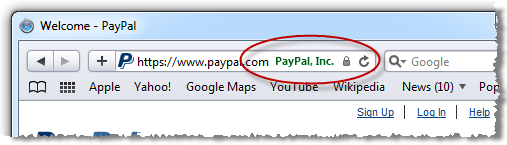

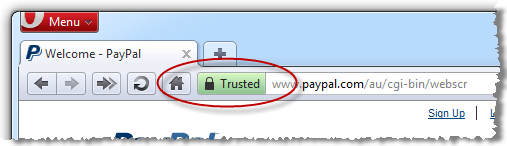

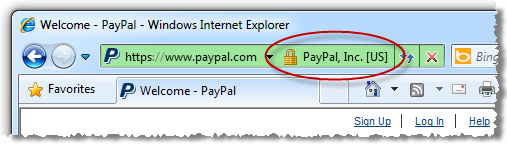

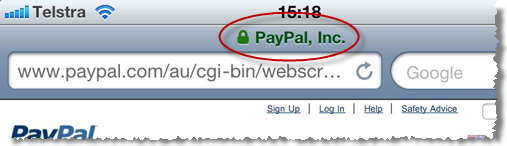

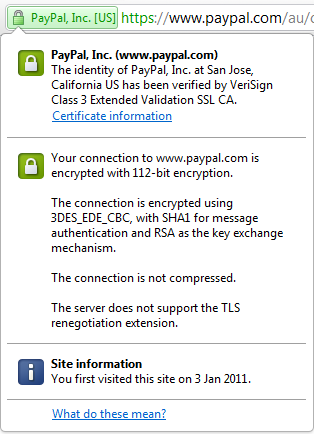

Every major browser has the ability to proactively advise you of the validity and authenticity of the site by providing positive, explicit assurance. This is usually done right up there on the URL bar and although there are idiosyncrasies between implementations, the concept is consistent:

Each one of these browsers, with the exception of Safari in the iPhone (Opera in the iPhone too, for that matter), provides further assurance by making details of the SSL certificate readily available:

The whole point of this exercise is to make verifying the legitimacy of the site easy for us and to give us confidence – explicitly – that our data will be encrypted in transit. And this brings us to the heart of the issue; not loading the logon form over HTTPS gives zero assurance of the authenticity of the site before submitting your credentials.

Exploiting the HTTP to HTTPS pattern

The simplest way to illustrate the risk of this is by looking at a typical man-in-the-middle attack:

The attacker makes independent connections with the victims and relays messages between them, making them believe that they are talking directly to each other over a private connection, when in fact the entire conversation is controlled by the attacker.

In an MITM scenario, we need an attacker at some point between the PC and the server. The very nature of the internet means there are many, many instances of data passing through intermediaries.

Imagine a typical wireless cafe scenario where you have the client connecting to a wireless router, exiting the premises by an internet gateway, travelling through the ISP then being channelled through potentially dozens of internet nodes before landing at the destination server.

The problem with requesting a logon form over HTTP is that it can be manipulated at any of these points and we’d be none the wiser. Let’s take a recent example of the Tunisian government harvesting usernames and passwords:

The Tunisian Internet Agency (Agence tunisienne d'Internet or ATI) is being blamed for the presence of injected JavaScript that captures usernames and passwords. The code has been discovered on login pages for Gmail, Yahoo, and Facebook, and said to be the reason for the recent rash of account hijackings reported by Tunisian protesters.

What was happening in this case was that the ISP was embedding a piece of script into the logon page of these sites. And just in case the ramifications of this weren’t entirely clear:

Four different experts consulted by The Tech Herald independently confirmed our thoughts; the embedded code is siphoning off login credentials.

But the real story – and relevance to this post – is a little bit further down:

The embedded JavaScript only appears when one of the sites is accessed with HTTP instead of HTTPS. In each test case, we were able to confirm that Gmail and Yahoo were only compromised when HTTP was used. For Facebook on the other hand, the default is access is HTTP, so users in Tunisia will need to visit the HTTPS address manually.

It didn’t matter that these sites were posting to HTTPS, just the fact that they allowed logon forms to be loaded insecurely was sufficient for the ISP to manipulate the contents and capture the credentials via JavaScript before they were posted over HTTPS. Had those logon forms been securely requested over HTTPS (as indicated in the Facebook example), the exploit would simply not have occurred.

A rogue ISP in a dictatorship is one thing, but consider what happens every single time you connect to public Wi-Fi. Take the Coffee shop Internet access scenario:

It’s kind of amazing that the way the Internet is designed, our gateway router can hijack our HTTP requests and we can’t stop it. In this case, we can see that the URL has changed in our browser after the redirect, but if a malicious gateway were transparently proxying our HTTP requests to an evil malware-laden clone of

www.google.com, we’d have no way to notice because there wouldn’t be a redirect and the URL wouldn’t change.

That’s more than a little worrisome and we expose ourselves to this risk every single time we connect to public Wi-Fi. Of course the problem is then compounded when you simply can’t access that explicit assurance of the site’s authenticity before handing over your credentials.

But there other ways of exploiting the HTTP to HTTPS pattern; DNS poisoning, for example. If you’re able to route requests to a legitimate address to a completely different host, you now have the opportunity to manufacture the contents on the rogue host – perhaps to mimic the Facebook logon page – which has obvious ramifications. But of course this won’t serve up a legitimate SSL certificate and its absence could be used to identify something being awry. But again, this only applies if an SSL certificate is expected before logon which is not the case with the HTTP posting to HTTPS pattern.

The OWASP position

Of course there are always other angles on these things so I sought some feedback through the Security Stack Exchange by asking the question Is posting from HTTP to HTTPS a bad practice? The accepted answer references the OWASP SSL Best Practices:

Login Landing Page Must Use SSL

The actual page where the user fills out the form must be an HTTPS page. If its not, an attacker could modify the page as it is sent to the user and change the form submission location or insert JavaScript which steals the username/password as it is typed.

Sound familiar? This brings us back to the point we’ve already established through the discussions above. If that logon page isn’t requested over SSL, you have no assurance of its authenticity.

Security doesn’t start and end at SSL

Before anyone else says it (there’s always one), no, properly implemented SSL does not guarantee any sort of security beyond the transport layer. Things could well be a total shambles from the web server onwards.

SSL also isn’t fool proof. There are numerous examples of it being exploited to one degree or another (200 PS3s used to break MD5, for example). It’s not easy, but it can be done.

The thing is though, SSL is the only outwardly facing assurance we have. It’s the one thing that’s ubiquitously used to create confidence in the integrity of the data and assurance of the site we’re transacting with.

To go to the effort of implementing it on the posting of credentials but consciously excluding it from the load of the logon page is just selling this essential layer of security well short of its potential. For the likes of Facebook, Twitter and even Dropbox to take this approach is very strange indeed.