There are few things more frustrating than trying to make other peoples’ code work; broken references, missing dependencies, extraneous and useless files – it’s all part of the joy of sharing the project love around. This is often tricky enough for people on the same team but throw in distance, culture and varying levels of expertise and things get ugly pretty quickly.

I come across these issues pretty frequently and the pattern is constant enough that I reckon it deserves just a little bit of effort to jot down some practices to streamline things. The concepts are pretty broad and generally interchangeable across technologies but I’m picking .NET examples because I can share some tangible stuff.

Oh – and if I’ve missed stuff (and I almost certainly have), whack it into the comments below for the benefit of others.

1. “It works on my machine” is not enough – no local references!

Here’s a good place to kick off: someone sends over a project, it hits the build server and… doesn’t. I mean doesn’t build. So let’s take a look inside the project file:

<Reference Include="System.Web.Http, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=31bf3856ad364e35,

processorArchitecture=MSIL"> <SpecificVersion>False</SpecificVersion> <HintPath>

..\..\..\..\..\..\..\Program Files\Microsoft ASP.NET\ASP.NET MVC 4\Assemblies\System.Web.Http.dll

</HintPath> </Reference>

See that? Unless you have that relative path with that DLL which is outside the project path, things are gonna break. In fact even if you do have a “Program Files” directory on the machine, if you nest the project too deep than the relative traversing back up to that folder is going to break.

Many times developers just simply don’t even realise the reference even exists, they nonchalantly added it at some point ages ago and of course everything continues to work just fine… on their machine.

2. No local installation dependencies either, please

Similar but different to the last point, you also don’t want to end up with the project only working when specific software is installed on the developer’s machine. You’re in for a whole world of pain here: it won’t (automatically) work on other machines, it may not build in a CI environment and it’s probably going to mean configuration on the server beyond just deploying it.

For example:

Myfile.aspx.designer.cs(220, 27): error CS0400: The type or namespace name 'MyStuff' could not be found in the global namespace (are you missing an assembly reference?)

Often this’ll be due to a dependency on assemblies installed by a process outside the scope of this project. For example, perhaps a library needs to be manually installed into the GAC or a particular product installed on the host OS, point is that you can’t just pull the project and run it. Now arguably there are cases where you simply can’t avoid this, but it should be a last resort not just because it makes life hard to integrate with your mates but also because it dramatically cuts down your hosting options. No more deploying to IIS as a service, for example, you’re going to need full control on the box so bye bye Azure websites and all sorts of other hosting options.

3. What’s this library do? Nothing? Get rid of it!

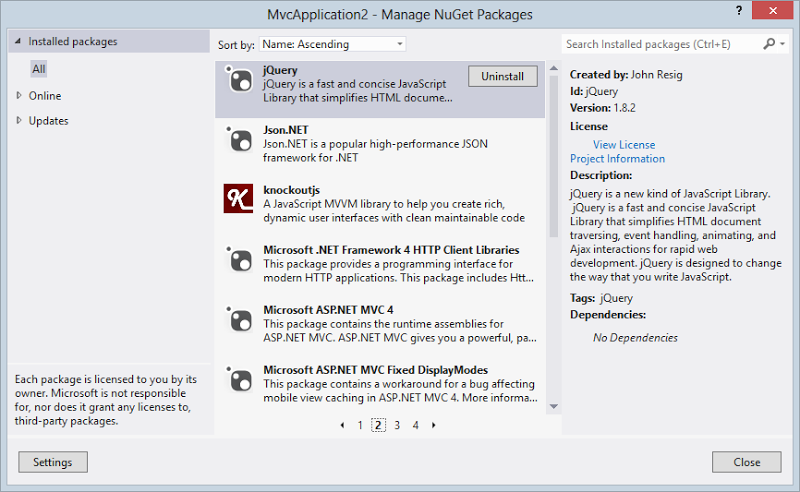

You get a lot of stuff in project templates these days. I get it, pulling in smaller libraries that can be independently and organically evolved outside the framework itself is just great, but really, do you need all those guys?! Let me give you can example: often I’ll see projects designed to be nothing more than an API that look like this:

These are just a bunch of default NuGet packages included in the Visual Studio template. Yes, they’re great. No, you don’t need jQuery in a project that only serves up JSON. Don’t need Knockout either. Or probably a bunch of other stuff on those subsequent pages either.

Why does this matter? Because it creates an unnecessary burden on the maintenance of the project. “Ooh, jQuery just updated to 2.0, should I take it?”. No, because you don’t need it! But speaking of versions…

4. Let’s not start with out of date packages

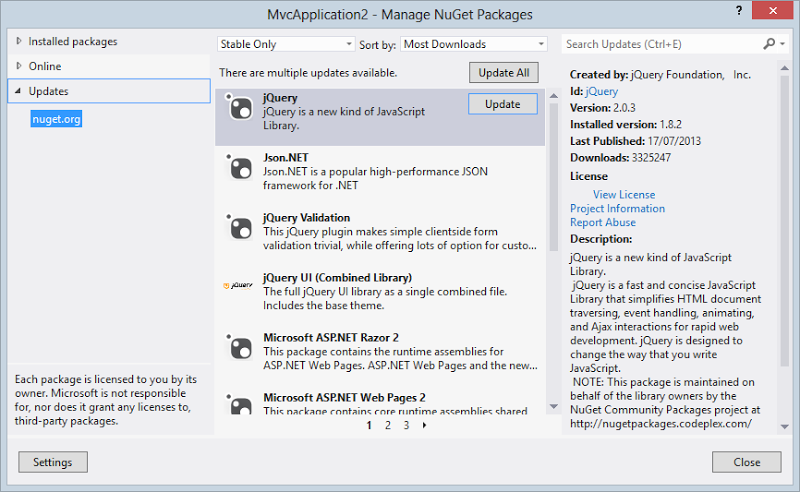

Here’s another thing that’s minor if you know the project intimately and painful if you don’t: out of date packages. No really, let’s look at a new project and see what needs to be updated:

So back to the jQuery situation: the original guy has sent it to me a few versions out of date, is that because he knows that version 2 won’t play nice with IE8? Or is that not important and he just didn’t think about it? Packages can cause breaking changes of various degrees: the other day I updated AutoMapper to 3.0 and things broke but Jimmy had an easy fix. But take Bootstrap 3 over 2; oh boy, you’re in for a world of pain!

When you see an ocean of out of date packages you just don’t know where to start. Particularly once you start adding your own dependencies, things start to get a bit out of control. It’s even worse when, as happened today, I’m adding Microsoft ASP.NET Web API Core Libraries to a project and it’s pulling down the current version but then you’ve got another project in the same solution referencing an older version. It’s almost always unnecessary friction.

5. I’m not really interested in all your temp files and failed experiments

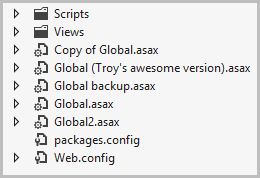

When I see this, I get a bit confused:

No really, which Global.asax was the good one again?! I get it – you play with things, you change your mind, you move on. This is why we have source control! This sort of pattern makes things extremely messy and makes no sense outside the context of the creator’s own mind.

6. Your commented out code is not welcome

In a very similar strain to the last point, this:

// All of this was crap and I've changed my mind - but I might change it back later

//AreaRegistration.RegisterAllAreas();

//WebApiConfig.Register(GlobalConfiguration.Configuration);

//FilterConfig.RegisterGlobalFilters(GlobalFilters.Filters);

//RouteConfig.RegisterRoutes(RouteTable.Routes);

//BundleConfig.RegisterBundles(BundleTable.Bundles);

//AuthConfig.RegisterAuth();

The solution is also the same – source control! If you change your mind, roll back later on. Create a feature branch if you really want to head off in another direction but for the love of clean code, don’t pollute the main body of work that other people need to live in with a veritable brain fart of unused code!

7. Your compilation output is yours!

When you build, stuff comes out. Assemblies. Binaries. Libraries. Call them what you will but you’ll get a bunch of DLLs (and probably PDBs, among other files). These are yours from your compilation. Compile again and you’ll get different ones.

What often happens is developers compile then commit the bin and obj files to source control. A couple of years back I wrote The 10 commandments of good source control management and made it pretty clear in number 8 the sort of problems with causes: constant conflicts, polluted commits with all sorts of unnecessary files, repository bloat and so on and so forth.

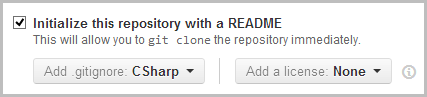

Here’s a tip: create a new GitHub repository and add a .gitignore for CSharp:

Now look at what the guys reckon shouldn’t go into the repo:

# Build Folders (you can keep bin if you'd like, to store dlls and pdbs) [Bb]in/ [Oo]bj/ ## Ignore Visual Studio temporary files, build results, and ## files generated by popular Visual Studio add-ons. # User-specific files *.suo *.user *.sln.docstates # Build results [Dd]ebug/ [Rr]elease/

I’ve cropped a lot of stuff out of there, but you get the idea. Temporary, user-specific or generated stuff does not go into source control! In fact I’ve been known to write Subversion pre-commit hooks in the past specifically to keep this sort of thing out of the repo to great effect.

8. The bin is where output goes, not input

I’ve partly covered this in the previous point, but the bin is where stuff goes when you build. In fact as you saw in the .gitignore file, the bin and obj files really shouldn’t even be going into source control in the first place. So how are you going to be putting dependencies in there?!

What often happens is the dev says “Right, I’m going whack my libraries into the bin then when I build, magic will happen and dependencies will be resolved”. What this means is that you end up with a bin containing a jumble of output from the project (which should be ditched) and external dependencies (which you actually need). Messy stuff.

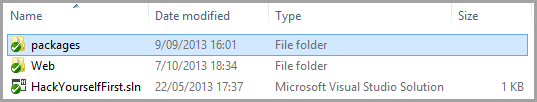

In a perfect world, packages are added via NuGet for all the sorts of reasons that make NuGet great. It means your solution root ends up looking like this one from my Hack Yourself First website:

Now I say “a perfect world” – not everything is in NuGet. When it’s not, whack it in a “libs” or a “refs” or even the “packages” folder (less ideal and a little ambiguous) and add the appropriate reference to the project. These paths are stable between builds, won’t get cleaned up by CI servers and they imply persistence. Bin and obj folders aren’t, will be and don’t.

9. You add assemblies from other projects with project references, not assembly references

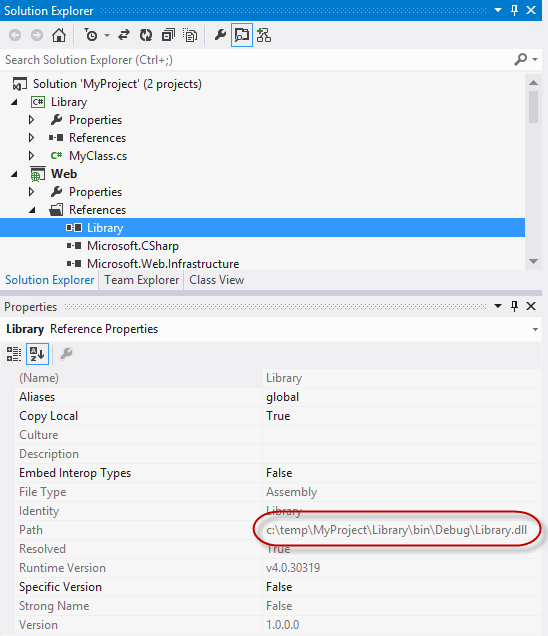

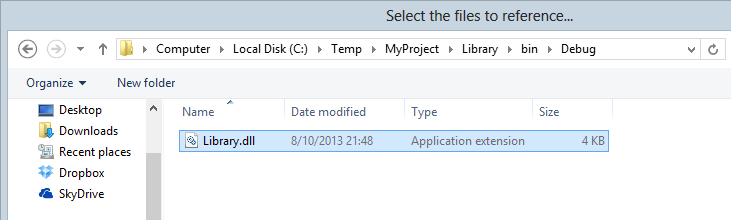

In case this sounds odd, yes, people do it and here’s what it looks like:

Now that image alone isn’t so bad until you change the build config to “Release” and then… that highlighted path doesn’t change. No really, it happens. What’s happened here is that someone has added a reference into the “Web” project that points directly to the output assembly of the “Library” project. Basically they just went “Add assembly” –> “Browse” then selected it from the bin:

One of the first times you realise what happened is when you try to build using a configuration other than “Debug”. No previous compilation output to reference? No build. On a build server in particular this is nightmare, especially if the build is cleaning up after itself and deleting the output.

Of course a project reference rather than a library reference has many other advantages as well and the guidance is simple: if you’re referencing the assemblies of another project in the solution, it’s a project reference!

10. Meaningless source control commit messages

This is a pet hate as it’s totally unnecessary and robs otherwise good-meaning developers of a valuable resource. When you put code in the repository – the flavour of source control doesn’t matter – you explain why you’re putting code in the repository! That means no commit messages like this:

- Committed

- Updated

- Changed some stuff

I know all that! That’s what a freakin’ commit is! It tells me nothing about why the code was changed and short of investing a heap of effort (relatively speaking) by looking at individual file changes and trying to draw my own conclusions on the intent, I just don’t know what’s going on.

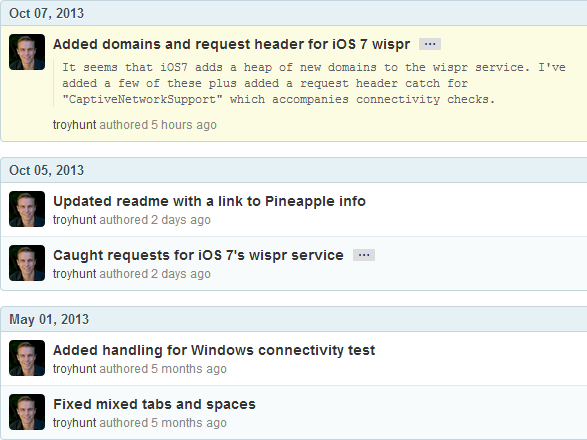

Now I’m fully conscious that this is one of those sometimes-religious sort of debates in terms of what constitutes a good commit message, but let me self-ingratiate for a moment and share some of my own from Pineapple Surprise:

Each commit message succinctly tells you why the change was made an in some cases further embellishes with detail that’s actually pretty useful if someone else needs to come along and figure out what the hell is actually going on. It’s just common sense. Just do it.