I’ve had a couple of experiences recently where guests have come to stay and then requested to jump on my wifi. In each case, I’ve declined and in turn they have expressed some degree of shock and outrage. Because it will happen again and because I don’t want upset guests staying in my house, allow me to articulate clearly and objectively why my network is off limits and why perhaps you too want to think twice about allowing access to yours.

It’s not that I don't trust my guests…

Let’s start here because usually just after “No, you can’t get on my network”, I hear “What – don’t you trust me?” and it’s entirely the wrong question for them to ask. The correct question is “What – you don’t trust other people?” to which the answer is an emphatic agreement – I don’t trust other people.

There are so many precedents of environments being compromised not due to malicious intent on behalf of the individual involved, but because of the access they have which is then exploited by a malicious party. That might mean as a result of introducing an infected machine into the network or picking up something unsavoury while they’re browsing around behind the confines of your firewall.

More than that though, there’s also the whole issue of social engineering. Humans are enormously susceptible to doing things they really ought not do simply because they’ve been asked to. They don’t intend to do the wrong thing, they’re just coerced into it without realising the ramifications of what they’re doing. That may mean being engineered into retrieving things from your network that may be accessible be that at the file level or even just simply the devices and services they’re running. More on that soon.

Access to networks be they home wifi or corporate should adhere to the principle of least privilege (emphasis mine):

In information security, computer science, and other fields, the principle of least privilege (also known as the principle of minimal privilege or the principle of least authority) requires that in a particular abstraction layer of a computing environment, every module (such as a process, a user, or a program, depending on the subject) must be able to access only the information and resources that are necessary for its legitimate purpose.

In other words, give people only what they need. This is a great principle to work by, but let’s start getting into some cold hard facts about the sort of stuff that goes wrong within a network.

Router DNS hijacking via CSRF

Typically, your home wireless access point takes care of resolving host names such as troyhunt.com to IP addresses such as whatever Google is running Blogger off at the moment. It does this via DNS servers which are configured on the router. Change your DNS servers to something else and another service starts doing name resolution.

Now imagine you change your router’s DNS settings to a server which resolves a request for something like mybank.com to hackerbank.com which serves up a phishing page. It looks like mybank.com and asks for your credentials, the only difference is that it’s not served over HTTPS. (Sidenote – this is why things like HSTS and HPKP are so important.)

But why would this happen? I mean why would my guest change my router DNS settings to something malicious? The answer is simple – they don’t. All they do is wander by a malicious site which causes their browser to make a request to the router’s admin page that sets the DNS servers to a malicious value and wammo! Now any clients within my network relying on the router’s DNS have a very good chance of having their traffic compromised.

There are many precedents of this happening. Here’s a good analysis of just one example, a quick Google for router dns csrf will show you many, many more. It doesn’t even have to be a malicious site the user browses to either, there’s enough precedents of ad networks being compromised to serve up malicious content to well and truly show that it could be perfectly innocent behaviour that leads to the compromise. Here’s a great example of millions of routers in Brazil using Broadcom chips being compromised in this way – millions!

Of course this only works if the router itself is vulnerable to a CSRF attack (although similar attacks exploit default passwords on routers) and I hope the new ones I just put in are resilient to this, but I also know how common it is for devices of this class to have issues. Of course I myself – or my wife – could easily browse to a site which attempts such an attack, but every additional party I add to the network increases the risk.

Malware

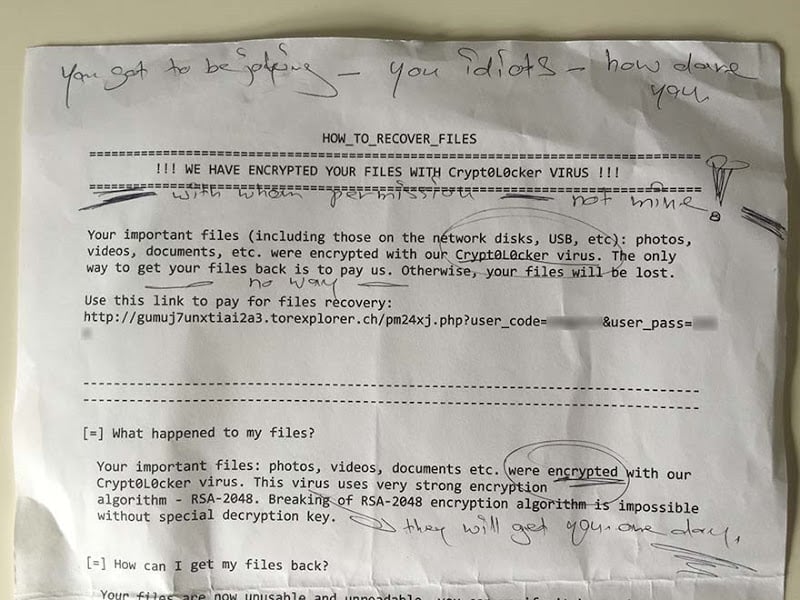

Literally just today, my mother in law gave me this (handwritten notes are hers):

This was from her PC, a PC she had previously wanted to put on my network. This is CryptoLocker and it’s enormously nasty stuff. It’ll encrypt everything on the host it can get its hands on and then hold it for ransom. It’s effective too; malicious intent aside, you’ve gotta hand to the guys that made this – they’ve done a very good job of it!

Now my mother in law never intended to get CryptoLocker any more than she’d intend to do nasty things within my network, but here we are. Under no circumstances whatsoever would I want any machine on my network running this sort of thing. Regardless of how well I think I’ve secured my environment, a machine running this sort of software is an absolutely unacceptable risk and you simply have no idea what people have on the devices they want to put on your network.

Because we’ve got way too much connected stuff

Think about what’s discoverable on your own network once a device joins it: all the devices and open ports just for a start. Your NAS, your media server, your security cameras and all manner of IoT things with nothing more than software to protect them. Just as with a corporate environment, you have to work on the assumption that any machine introduced to the network is malicious and frankly, I want to minimise that risk as far as possible.

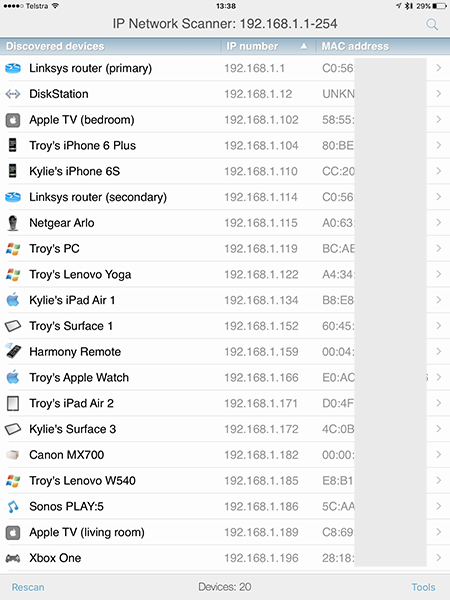

I just took a quick look at mine and found 20 connected things at this moment (this is the IP Scanner app for iOS in case you’re curious):

Run a tool like Nmap over your home network and see not just how much stuff you have connected, but what ports are open on them too and you may well get a bit of a shock. It’s only my wife and I that have connected devices (the kids are a little too young yet), but here we have 20 things that can be scanned, probed and possibly in some cases, exploited. Anyone who connects to my network can see all of this and partake in the aforementioned scanning. Again, it’s not that I suspect my guests of being malicious (they could always sneak into the office and plug into the router if they wanted to), it’s that I don’t trust their machines.

Wifi Sense and sharing credentials

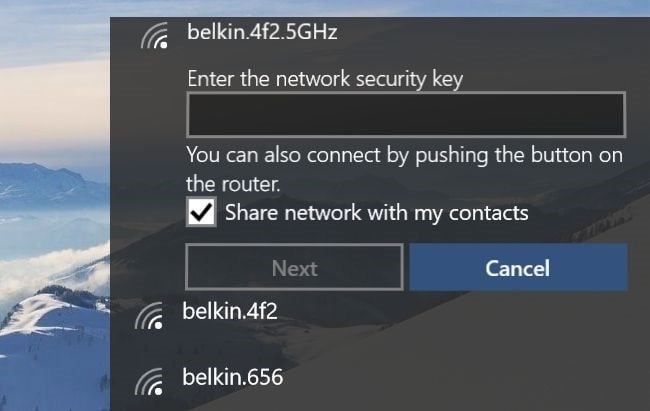

Ok, I get the convenience of this but in no way and no how am I ever going to put someone else in the position to do this:

Windows 10 Wifi Sense is the idea that the networks you join should be shared with your friends, you know, like whoever you’ve befriended on Facebook. I get the usability upside of further socialising connectivity such that more people can get online in more places but no, that doesn’t mean I want my guests inviting their friends to join my network!

Now of course I could request they hand over their machine and I enter the wifi password whilst carefully ensuring this box isn’t checked, but of course this will still be met by a bit of “What – don’t you trust me?” again. I also don’t feel inclined to rename my home network with the “_optout” suffix simply to prevent it from being Wifi Sensed, I’d rather just not put myself in that position to begin with.

Guest networks

Of course you could always just defer to your wireless access point’s guest network (if you have that capability — and many do not), that’s what it’s designed for, right? The basic premise is that a guest network is a logically isolated network for exactly what the name suggests – giving guests access. This keeps them separated from your primary network which is a good thing, except the implementation can be kind of sucky.

I have a current gen Linksys and the guest implementation is similar to what I’ve seen on other devices; open network with a web page challenging for a password. Problem is, after a day the session expires so you need to log the guest back in. Inevitably, they’re going to ask for the password after a couple of goes at that which means now they have persistent access. I could change it after they go, but it puts more onus back on me to “secure” my network again.

I’m also just a little uneasy about how well router manufacturers do their network isolation. Whilst you’d hope the likes the Linksys get it right, there’s some big names out there that have produced fundamentally flawed implementation in the past (the DNS CSRF example is perfect). But ultimately it’s a bit of a moot point anyway because my guests have never actually needed my wifi, they’ve always had their own wireless access point with them…

Because 4G is so damn good these days

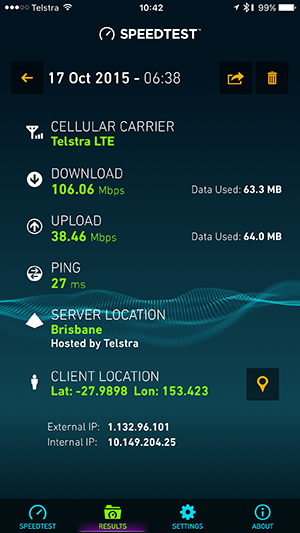

For me though, this is the key: it’s not about having connectivity versus not having it, it’s about whether it’s my connection or their connection. Every person that’s asked me for access has carried a very capable wireless access hotspot in their pocket. In fact it’s one that has way better connectivity than most internet connections here in Australia anyway:

So here you are with a device doing more than 100Mbps down which can also act as a hotspot for your laptop and you want to jump on my network instead? Granted, in Australia we often only have limited cap on our monthly download limits, but we’re talking $10 for a GB of data if you go over (at least that’s the case with Telstra).

Here’s the best thing you can do for your guests: help them enable the wireless hotspot capability of their device and teach them how to get connectivity anywhere. They’ll be better off with their newfound mobile capability and you’ll be better off for not having them on your network. It’s not just that you shouldn’t want unknown elements on my network, it’s that they simply don’t need to be there in the first place which is entirely the point of the principle of least privilege. Ultimately though, it’s your network and regardless of how much someone may or may not buy into the thought process above, you get to call the shots.

Edit: I'll add one more thing for the folks suggesting I buy dedicated hardware and likewise for those concerned about international visitors — I've got one of these Telstra Pre-Paid 4GX Wi-Fi Plus mobile hot spots. It cost me $99 to load up 16GB of data I can use over the next 2 years and after the tax deductibility of it all, that's a few bucks a GB. Fast wifi at a very low cost for reasonable guest usage with zero risk to my environment.