Back in the day when the British had a penchant for conquering the world, they ran into a little problem on the subcontinent; cobras. Turns out there were a hell of a lot of the buggers wandering around India and it also turned out that they were rather venomous which didn’t sit well with the colonials. Ingenious as the British were, they decided to offer the citizens a bounty – you hand in dead cobras that would otherwise have bitten some poor imperialist and you get some cash. Problem solved.

Unfortunately, the enterprising locals saw things differently and interpreted the “cash for cobras” scheme as a damn good reason to start breeding serpents and raking in the dollars. Having now seen the flaw in their original logical, the poms quickly scrapped the scheme meaning no more snake bounty. Naturally the only thing for the locals to do with their now worthless cobras was to set them free so that they may seek out a nice cosy British settlement somewhere.

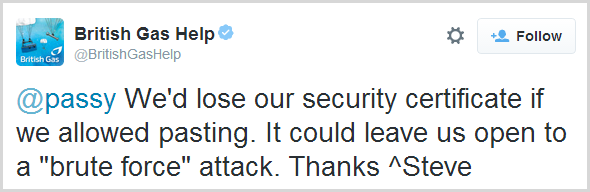

This became known as the Cobra Effect or in other words, a solution to a problem that actually makes the whole thing a lot worse. Here’s a modern day implementation of the Cobra Effect as it relates to the ability to paste your password into a login field:

Let’s just allow the nuances of that one to sink in for a moment…

I imagine Steve was picturing armies of elite hackers working through password dictionaries with the old CTRL-C / CTRL-V and the ICO then sweeping in and taking British Gas’ proudly mounted security certificate down from the wall in the foyer. That’s about the best I can come up with, but let’s not single out British Gas here, this is a far broader issue than just them.

For your security, we have disabled pasting of passwords

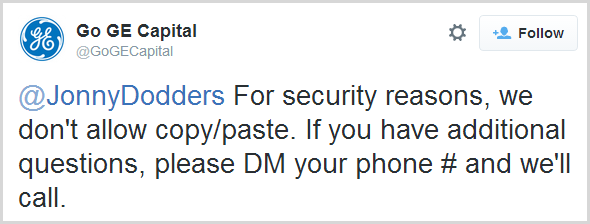

As far as amusing infosec tweets go, British Gas did a fine job but there are plenty of others who also reject the ability to paste into the password field as well, albeit with less humour:

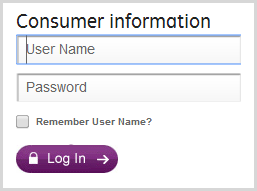

But what does this actually look like? I mean a website can’t disable the fact that your operating system and browser have some form of equivalent of CTRL-V, so what happens when you paste? Here's Go GE Capital before logging in:

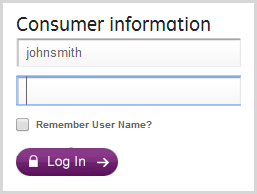

Now here they are after entering the username and pasting the password:

Right…

Go GE Capital just kills whatever is pasted, it disappears in the blink of an eye. No warning, no “For your safety…” message, just goneski.

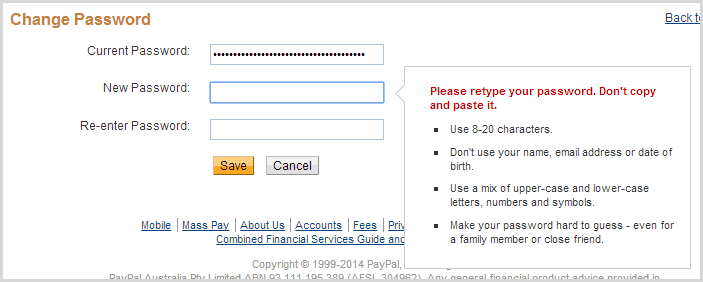

PayPal take a slightly different approach on their change password page:

Ok, you get a message which is nice, but zero info on why you shouldn’t be pasting in your password. I’ll come back to this example later on though because there are other things going on here which help explain their rationale.

Before we go on though, let’s take a quick look at the mechanics behind the anti-paste mechanism so we can better understand what goes into saving us from ourselves.

The mechanics of an anti-password-paster

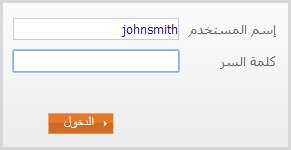

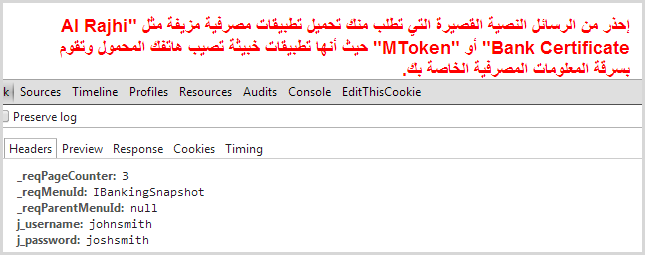

Right, let’s drill into this and see what’s going on behind the scenes. We’ll pick someone different this time, let’s try the Al Rajhi Bank in Saudi Arabia just for a change of flavour. As you can see below, I’ve typed in a username and pasted a password:

Yeah, about that password… Anyway, the question remains, what voodoo is breaking this most fundamental of behaviours? For Al Rajhi, it’s very simple:

<input type="password" name="j_password" class="DataPasive" maxlength="14" size="23" onkeypress="return logonWithEnter(event)" autocomplete="off" onpaste="return false">

That’s it – the onpaste event is returning false. Sound unfamiliar? I mean the onpaste event? Yes, it’s a thing, here’s a JSFiddler so you can play with it yourself. But there’s also this regarding the event:

Non-standard event defined by Microsoft for use in Internet Explorer.

C’mon guys, we’ve been down the non-standard implementations in browsers before and it always ends in tears. Thing is though, not only does it work in IE but it works in Chrome too. And Safari. And Firefox. And even if it didn’t, there are always bright JavaScript ideas to “hack” the ability of CTRL-V out of browsers.

The point is that there are many ways of skinning this cat and it can be very easy. However, it’s a conscious decision – the developer has to say “You know, I really don’t think people need a paste facility, I’m gonna kill it”. But of course we really should touch on why people want to paste into password fields to begin with so let’s cover that off now.

Why on earth would you want to paste a password anyway?!

The argument of whether you should use a password or a passphrase or just let the cat wander over the keyboard and see what happens has been well and truly had and in the end it always comes back to this: The only secure password is the one you can’t remember. If you haven’t already reached this enlightened state then free yourself from the shackles of human memory-based passwords and grab 1Password or KeePass or LastPass.

The premise of all of these is that you delegate “remembering” your password to the password manager and instead the only real memory required (at least of the human variety) is to remember the single master password that gains you access to all the other ones. Again, the debates on the pros and cons of this have been had so go back to the aforementioned blog post and read the comments if you want to jump on that bandwagon.

Once a password manager has the credentials stored, clearly at some point in time you want to get them back into a login form and actually use them to gain access to the website in question. Password managers like 1Password can make this profoundly simple in that they have the ability to auto-fill the login form of the website in question. For example, I was able to successfully use it to attempt to login to the Al Rajhi bank:

As you can clearly see from the red error message, the login credentials were incorrect (I’m guessing “johnsmith” may not be that common of a name amongst their customers). But as you can also clearly see from the request headers, both the username “johnsmith” and the password “joshsmith” were successfully sent. In other words, whilst that non-standard onpaste implementation may be blocking the old CTRL-V, 1Password’s ability to auto-fill the form is not hindered.

However, clever tricks like auto-fill don’t always work. Sometimes the name of the form field changes either due to the site being revised or because of a perceived value of rotating and obfuscating the ID of the field. Sometimes you want to use the same credentials on multiple domains of the same service and auto-fill only works against the domain the pattern was recorded on. Sometimes you’re in iOS and you really just want to use Safari so you copy from the 1Password app and paste into the browser.

There are many, many valid reasons why people would want to paste passwords in order to increase their security profile yet the perception of those blocking this practice is that it actually decreases security. Why? Interesting you should ask…

Because we’ve been bad, please create a weak password

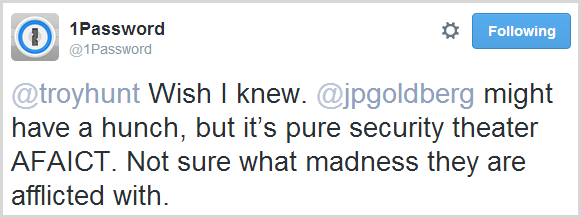

I was admittedly mystified by this practice so I asked around and got a whole range of answers along the lines of “because some developers are just stupid”. Hard to argue with that although in fairness, this is often something dictated to them (although perhaps they should be doing a better job of articulating the counter-reasons). I thought I’d ask 1Password given these guys spend a bunch of time thinking about how to securely get creds into websites. They pretty much concurred with everyone else:

Security theatre madness. Sounds about right.

But there’s one angle to this that helps explain the madness and it goes back to that earlier PayPal screen grab. This was of the change password page, not the login page. You can easily paste into the login page and in fact you can even paste into the original password field on the change password page, just not the new password field or the other field that confirms it.

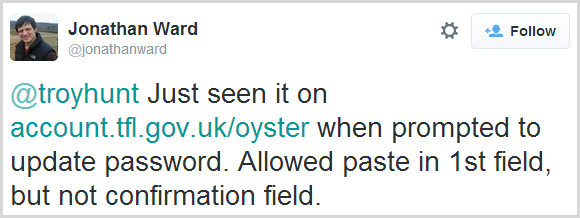

But it’s not just PayPal, apparently it’s the same with the Oyster Card site in the UK:

You can easily paste into the password field of the login page for the Oyster card, but apparently you can’t on the change password page. The reason lies in the earlier message I showed from PayPal, in particular this part of the password criteria:

Use 8-20 characters

Ah, so because you’ve gone and put an arbitrary limit on the length of my password and taken away my ability to create a nice a 50 character random string, you’ve had to kill the paste function because otherwise I’d go around thinking I’ve got a 50 char password but it was actually truncated to 20 due to the maxlength attribute of the password field. Nice one guys, good work there, bet you’re saving a bundle of ingress data costs by cutting out those extra bytes!

This, of course, is madness. Once passwords are stored, the hash of a 50 character password is an identical length to that of a 20 character once which incidentally, is also identical to that of a 100 character one. (Of course also keep in mind that there’s a lot more to password storage than just hashing) All of you creating these low arbitrary limits are actually hashing our passwords, right? Guys?

I’ve written about why we’re forced into choosing bad passwords in the past and there’s never really a good reason, just various shades of bad reasons. That these bad reasons must then extend to disabling customers’ ability to use a password manager to at least randomise the characters within the allowable limit only compounds the problem.

Here’s an idea – if you really want to force people into creating short passwords because [insert baseless reason here], how about just watching for when the password field suddenly has the maximum number of allowable characters in it without the corresponding number of onkeypress events and then saying “Excuse me, you’ve pasted a password we can’t accept, could you please weaken it somewhat?”

But, but, but… malware could steal your login, yeah, that’s it, malware!

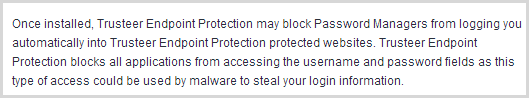

There is a counter-argument to pasting passwords and it goes like this: if your computer is infected by malware, the nasties inside it may be able to access your clipboard and steal the password you copied onto it. Sound crazy? Trusteer doesn’t think so:

Of course the irony of this position is that makes the assumption that a compromised machine may be at risk of its clipboard being accessed but not its keystrokes. Why pull the password from memory for the small portion of people that elect to use a password manager when you can just grab the keystrokes with malware? Crikey, the operating system itself doesn’t even need to be compromised to do that, you just grab a cheapie keylogger off the web and plug it into someone’s USB keyboard. Job done.

In summary, just don’t

Of course it all comes back to this balance in security where there are no absolutes and things are often a trade-off between cost, convenience and actually making the web a safer place. But in the case of passwords, one of the best damn things anyone can do is get themselves a password manager and stop typing in that same crappy combination of kids birthday and dog’s name they’re using all over the place.

In the examples above, we’ve got a handful of websites forcing customers into creating arbitrarily short passwords then disabling the ability to use password managers to the full extent possible and to make it even worse, they’re using a non-standard browser behaviour to do it!

Hey, I’ve got an idea – maybe I should offer a bounty where if anyone comes to me and demonstrates that they have a crappy password on a site but is then able to kill it off and create a secure one, I give them some cash. What could go wrong?!