Browsing through my Facebooks the other day, I came across an interesting little sponsored ad:

Banking, you say? In your Facebook, you say? What could possibly go wrong?!

The overriding concern that immediately sprung to mind was that you’re mixing two domains of a very, very different nature. On the one hand we have our social media, frequently the source of status updates about our breakfast, commentary on the latest lolcats and as I’ve written on numerous occasions before, favoured channel of scammers. On the other hand we have our financial well-being, records of our earnings and a domain which we generally expect to hold to the highest possible standards of security.

Of course there is also intersection: sometimes our social network intersects with our financial network and indeed CommBank frequently draws attention to the ability to pay friends in their promo material. But does the intersection of these two polar opposite domains pose entirely new risks to online banking? Will the higher prevalence of security risks in social network undermine our banking security? Let’s take a look.

Understanding the mechanics of Kaching

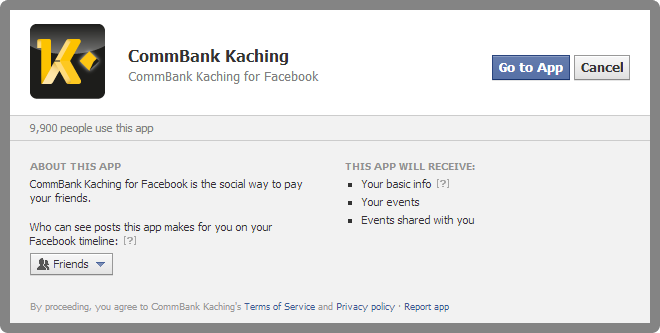

Firstly, there’s a Kaching app that you need to opt into:

It’s not entirely clear what kind of material CommBank wants to post to your timeline (although there’s a small example of one use case later on), but that in itself is a rather novel concept; do you really want your bank telling your friends what activity you’ve been performing?! (“Troy – you’re overdrawn again!” – but I’m sure that would never happen…) The event info the app is requesting access to is used so that you can make a payment to someone, say, on their birthday.

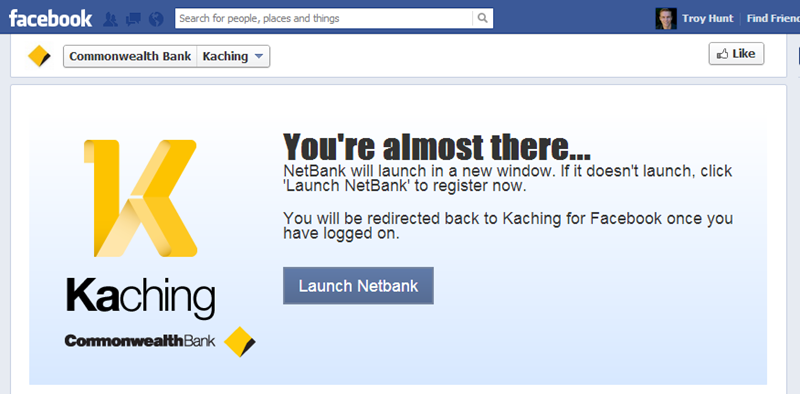

Once this is done you need to jump off to CommBank and continue with the setup but not being a CommBank customer, everything I’m going to write about after this gets taken from publicly available material they’ve published:

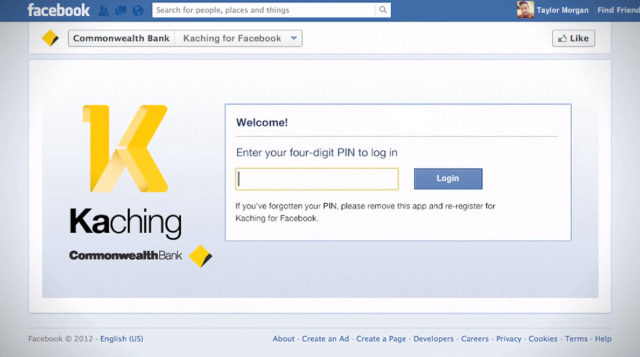

Once this process is complete (I assume it’s an association between your CommBank account and your Facebook account), the intro video shows the user using a 4 digit PIN to login from within Facebook:

Now of course the app is being served by CommBank, it’s just within a Facebook shell. The URL you’ll see is Facebook, if you inspect the certificate for the site it’s Facebook and of course you’re trusting Facebook – not CommBank – to serve you the legitimate Kaching app. I’ll come back to that a little later.

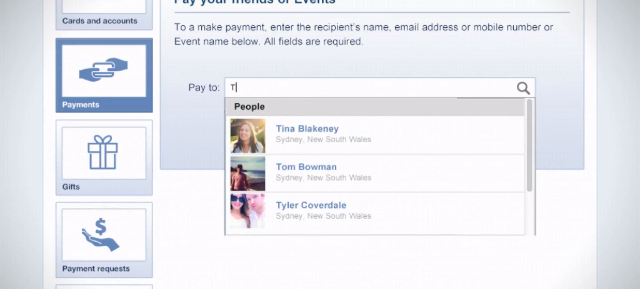

Once you’re logged into Kaching and ready to make a payment, the Facebook value proposition becomes a lot clearer:

Obviously this is just the app accessing your friends list. Hey, it’s a hell of a lot easier than typing a BSB and an account number!

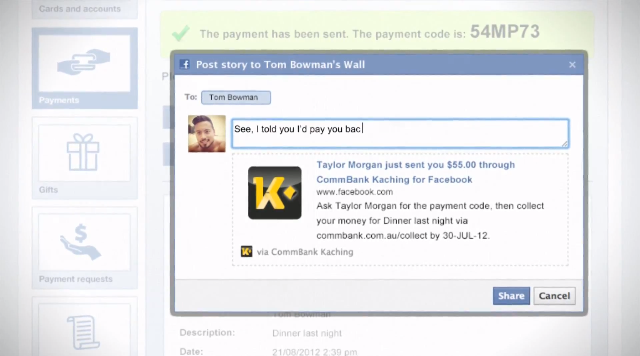

Once you’ve made the payment you can do what everyone apparently does with every event in their lives these days – share it via social media!

I’m not sure posting on someone’s wall is the ideal way to handle financial transactions but hey, maybe it appeals to some people.

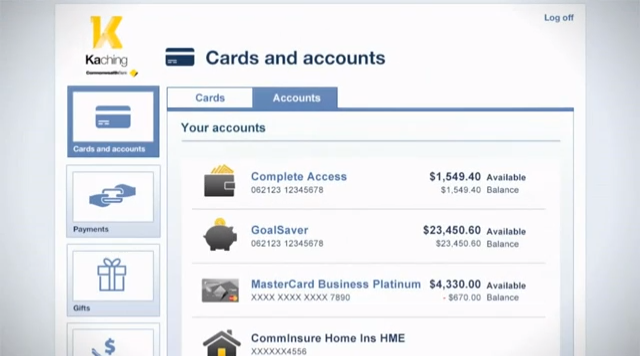

Kaching apparently also provides facilities to review your banking accounts:

This is probably what made me feel the most uneasy – potentially seeing my personal finances appearing on facebook.com next to Farmville updates.

There are also facilities to send gifts or request payments which of course are all variations of the same things – payment fulfilment.

Counterfeit apps and wall posts

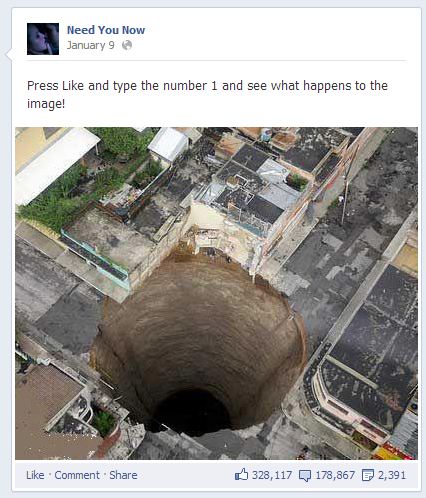

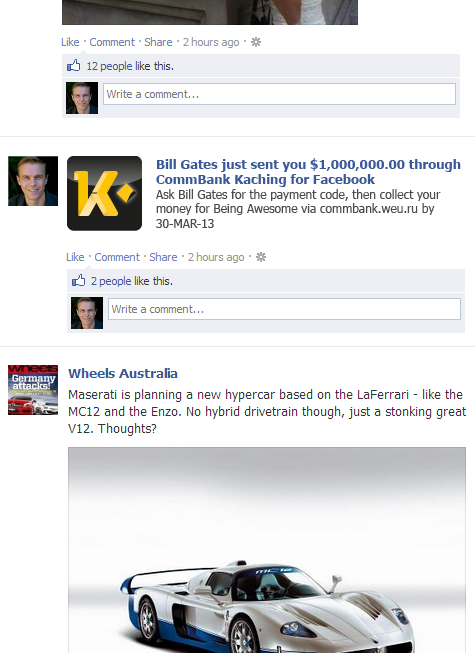

Here’s the primary concern I have about extending your banking through a domain like Facebook: there’s a lot of crap on Facebook. No seriously, consider an example such as this:

Hundreds of thousands of people genuinely believed that if they liked the photo then something interesting would happen. It didn’t.

Or take scams such as the Woolworths one:

No free gift vouchers and the scam remained rampant for a long period without Facebook taking any action (which they could have).

These scams are now going to sit alongside requests for payment via Kaching and as we well know, if us humans – hundreds of thousands of us humans – are gullible enough to think that likely a photo will cause something interesting to happen, what else will we be convinced by? How about a similar approach to the Woolworths scam complete with Kaching branding and the promise of some free cash if you use the service? Of course you’ll need to provide your PIN to login, please…

Or since we’re being devious, a manufactured wall post that innocuously sits on your timeline with the hallmarks of being legitimate, except it isn’t:

Now of course phishing scams are nothing new and we see them all the time, just check your junk mail and there’ll be a dozen of them in there leading through to carefully constructed websites designed to imitate the legitimate version. Indeed this is one of the reasons why security advice from banks (among others) is usually “Always type the address of the bank into your browser using the HTTPS scheme”. Now, however, the advice changes such that users are logging into their Facebook and somewhere between all the usual inane content is the ability to do things with real money.

When we log into our banking the traditional way, we’re there for a very discrete purpose. The site is also solely focussed on providing financial services and anything outside the scope of this would be unexpected and immediately raise suspicions. Not so with Facebook because frankly, you expect to see a bunch of crap there and you expect to see scams, hoaxes and any manner of other odd, non-banking related material.

Lowering the bar on the weakest link

Banks put a huge amount of effort into securing their resources and indeed it has always been that way. These guys have always been at the forefront of security (arguably one of the only comparables would be military purposes), whether it be safes (I mean physical ones – the ones with big locks) or process reconciliation (are we losing cash anywhere) and certainly that extends to IT systems too. This is serious security and in the scheme of common vulnerabilities, banks fortunately pop up a lot less frequently than other classes of service.

The thing about embedding your banking within another service is that to a degree, the overall security profile is reduced to that of the other service. For example, when the Kaching app loads you’re trusting Facebook to load the correct content. All things going well, Facebook will give you the legit app. Something goes wrong (XSS, counterfeit app, etc) and you get, well, not the Kaching app (even though it might appear to be the Kaching app). Oh – and you can’t easily inspect the legitimacy of the certificate because you can’t readily see the domain the content is loaded from, the address bar just gives you facebook.com.

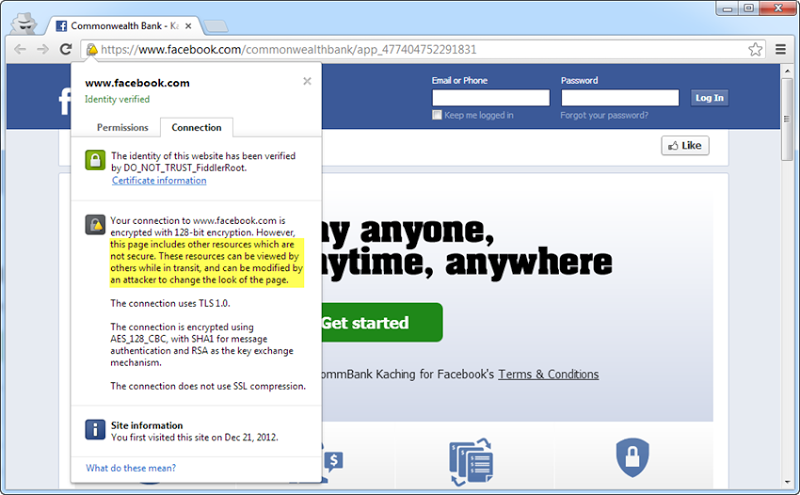

Here’s another example of where things start to get a bit worrying; this is the Kaching app as it stands today:

Chrome is kindly telling us that whilst the page on facebook.com has been loaded over HTTPS, other assets on the page haven not been hence the little yellow warning triangle. As you’ll see in my highlighting, the risk is that those other assets may be intercepted, read or even modified and it’s the latter that we’re worried about.

The problem with loading content over an insecure connection is that any asset can be modified in transit. A couple of years ago I explained how SSL is not about encryption and included a reference to how government controlled ISPs in Tunisia were injecting script into Facebook login pages loaded over HTTP. Even though those pages posted to HTTPS, by then it was too late as the government had already injected credential harvesting script into the page which asynchronously sent usernames and passwords to the authoritarian regime when citizens logged on.

It’s a similar risk in the image above; those assets loaded over an insecure connection may be modified by a man in the middle. Those assets included, among other things, a Flash file loaded over an unencrypted connection from commbank.com.au so now you have to ask “What damage could be done if an attacker could embed their own Flash file in the page above”? Plenty.

Is “100% secure” even possible?!

I’ll admit to being a bit suspicious of the following image, but hey, it’s got a padlock so it must be secure:

It’s a bit like saying a Mercedes Benz S class is 100% secure; it’s a very safe car, no doubt, but pure physics means that if you hit a truck head on at 100kph then you’re a goner.

Of course Kaching isn’t 100% secure and there’s a subtlety in the wording that avoids being quite so brazen despite what it implies. What CommBank is really saying is that if you suffer a loss as a result of using the service, they’ll cover it for you assuming you adhere to their terms and conditions. These terms include:

- You should always take precautions when using CommBank Kaching for Facebook (sounds like the classic “reasonableness” clause)

- You must never keep a record of the PIN with your phone (what about password managers?)

- You must notify them immediately if your Facebook account has been compromised and suspect someone may have unauthorised access to your CommBank Kaching for Facebook (sounds fair, wonder if calling the bank is the first thing people think of after their Facebook is pwned though)

In reality, I suspect none of this is very different to the assurances banks offer when using their more traditional online services, it’s just the representation of “100% security” which is misleading.

What will be interesting is when someone is defrauded by a Kaching scam running through Facebook. Not necessarily directly via Kaching, mind you, but a scam which preys on the fact that the victim has been conditioned to do their banking through Facebook so it may not appear out of the ordinary. But because it’s not the Kaching service, where does that “100% security guarantee” sit? Will CommBank cover the losses? It’s highly doubtful and really, nor should they, but they were partially responsible by normalising Facebook-based payment as a legitimate service and desensitising people to the risks. That might be a controversial position and time will tell whether I’m right on that or not.

Kaching or Kaput?

I’m not saying Kaching isn’t secure (although I will say it isn’t 100% secure!) and no doubt there have been huge resources invested in making it the best possible experience with as much security as is practical under the obvious constraints. Personally, I’ll let others be the guinea pigs on this one and this is coming from someone who’s pretty adept at spotting (and so far avoiding) online scams.

Perhaps the future of banking is a social one, a future where our Facebook friends and our bank accounts live harmoniously on the one page. But frankly, until I have confidence that the same page isn’t being inhabited by crooks running scams then it’s all a little bit too early for me.