Back in September last year we saw the emergence of the padding oracle vulnerability which suddenly got a whole lot of ASP.NET developers very nervous. The real concern with this vulnerability was that there really wasn’t much you could do at the code level beyond a couple of little tweaks – what was really needed was for patches to get installed on servers and fast.

The problem back then was that, well, you couldn’t always trust your hosting provider. Hosting providers take all sorts of different shapes; corporate servers managed by IT groups, dedicated machines with dedicated hosts, shared co-tenanted machines and now more and more frequently, cloud based solutions. But one thing remained constant and that was that the patch Microsoft had quickly released needed to get onto the machine.

Back then I talked on my blog about how to remotely detect the patch. But what I didn’t talk about was that I’d written an app to automate this check. Like many with responsibility for a number of sites, I was too busy making sure things were patched to get that little piece of software into a form suitable for sharing. Today, things are a little different…

Welcome to ASafaWeb (again)

I introduced ASafaWeb to the world only a few weeks back. The objective was to create a very simple, very easily consumable and free tool which would both scan for ASP.NET configuration vulnerabilities and help educate developers. What I haven’t mentioned until now is that ASafaWeb has its origins back in the padding oracle vulnerability days; the concepts I used to automate scans back then have been reused and whilst the codebase is all new, the purpose remains.

What this means for the hash DoS situation is that it was very easy to add a scan for the vulnerability to ASafaWeb. Please note that this is not a scan that exploits the vulnerability, rather it’s a scan that checks for the presence of the patch from Microsoft. More on that shortly, let’s quickly recap on what this hash DoS situation is all about first.

Background: what is the hash DoS and why should you care?

This is actually an elegantly simple little attack with potentially severe consequences. The best way to truly understand what this is all about is to watch the video below of Alexander Klink and Julian zeri from the Chaos Communication Congress in Berlin earlier this week:

Understand all that? Good! No? Here’s the tl;dr version:

A hash table is data structure which maps keys to values. It’s a particularly efficient data structure and it’s used very broadly across many programming languages. This data structure is used in ASP.NET to store the parameters received in a POST request (what we’d normally think of as “form data”). So far, so good.

The problem though is that when two or more strings are hashed, there’s the potential to create what’s referred to as a hash collision which simply means the two discrete input values both end up with the same hashed value. This alone isn’t a big deal and there are mechanisms built into frameworks like ASP.NET to handle this scenario when it occurs.

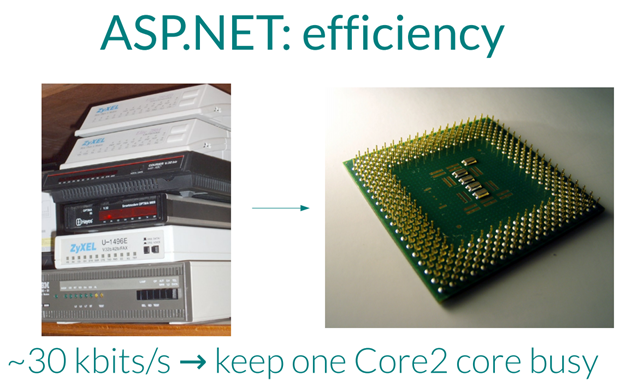

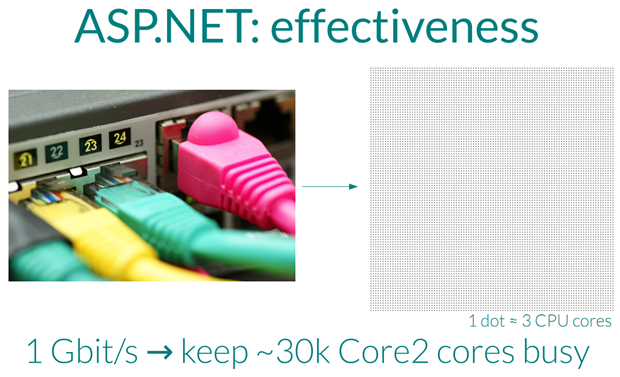

But the real problem is that if you create enough hash collisions from enough form parameters then the CPU goes, well, a little bit nuts. How nuts? These two slides from the boys summarise just how little data is required to be sent in order to keep an awful lot of CPUs too busy to do anything else:

Now, the problem is that once the CPUs are too busy to do any legitimate work, you effectively have a denial of service attack or “DoS”. In simple terms, your website is stuffed; it simply no longer responds.

But the real problem is that exploiting this vulnerability is dead simple, all you need to do is post the right form data to a vulnerable site. There’s already a very simple example of how to exploit this against PHP here. In this example, there are 65,536 form values (well actually, they’re just names without any values), so we’re not talking small numbers here. This is what we’re looking at:

- EzEzEzEzEzEzEzEz=

- &EzEzEzEzEzEzEzFY=

- &EzEzEzEzEzEzEzG8=

- &EzEzEzEzEzEzEzH%17=

- …

It would be a piece of cake to construct an HTTP request in this fashion so it’s a very easily exploited vulnerability indeed.

Microsoft’s patch

Alexander and Julian actually disclosed this vulnerability to Microsoft on Nov 29, well in advance of their presentation. Fortunately there has been enough time for a patch to be prepared and it is now available as part of Microsoft Security Bulletin MS11-100, along with a few other bits.

In the video above, it’s suggested that mitigation techniques could include changes to the hashing behaviour, applying a limit to the CPU cycles a request could consume and limiting the number of parameters which may be posted to a page. It’s the latter that Microsoft have implemented in their patch.

Testing the patch

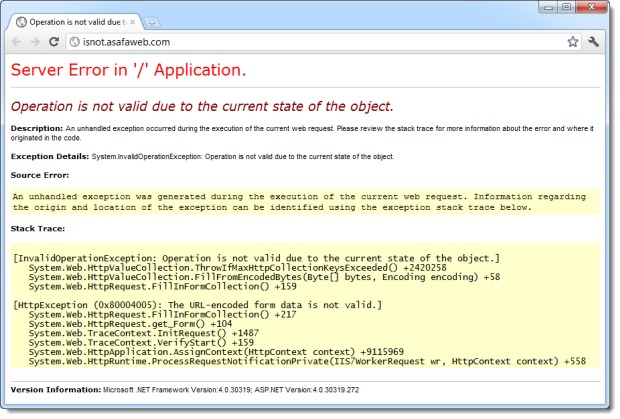

What Microsoft has done is set the limit of form variables in a POST request at 1,000. Any more than this and you’re going to get an error which looks just like this:

Well actually, you should have custom errors configured correctly so that your visitors don’t see an error like this. The screen above is from the deliberately insecure test site for ASafaWeb at isnot.asafaweb.com and I’ve just posted 1,001 form variables to it. This site runs on AppHarbor who very efficiently applied this patch within hours of it being released.

The way the test for the patch works is that ASafaWeb simply posts a request with 1,001 sequentially incrementing form variable names like this:

- 0=

- &1=

- &2=

- &3=

- …all the way up to “&1000=”

This is not intended to cause a hash collision! This is really important as the goal with ASafaWeb has always been to play nice with the sites it scans. This request is simply intended to see if the site happily processes the request or if it throws an error. As error messages can take all shapes and forms and can be returned within a successful HTTP status code (a 200), ASafaWeb is looking to see that the response from this request is different to the response from a simple GET request to the same page.

Before the responses are compared, a bit of cleansing goes on to take out the organic differences you’ll get from legitimate subsequent requests to the same page (i.e. different advertisements, View States, form IDs, etc.) This is the same process used to test for request validation on web forms apps and has proven to be quite reliable, albeit not fool proof.

Summary

I’ve tried to turn this scan around pretty quickly as I know people are anxious and want to test their sites. I’ve absorbed as much as I can from Alexander and Julian, Microsoft and the endless stream of community tweets and I believe the above info – and the ASafaWeb scan test – is accurate. I’ve also tested a bunch of sites which I know either do or don’t have the patch installed and the scan results have been consistent with the known patch state. But as always, if I’m wrong on any point, please let me know so I can get things back on track.

The scan for the hash DoS patch can be run right now at asafaweb.com