Just when you start thinking we’ve seen out the last of the major security breaches for 2011, Christmas day brings us one final whopper for the year: Stratfor. Much has already been said about why they might have been hacked and who might (or might not) have done it, but the fact remains that there are now tens of thousands of customer passwords and credit card details floating around the web. Oh, and apparently about 5 million internal emails ready to be released.

So what do we take from this as website builders? The benefit of hindsight gives us a good opportunity for reflection as we watch the fallout unfold from the last major breach of the year. Let me share the 5 lessons I’m taking away from this.

1. There doesn’t need to be a reason for you to be hacked

The whole hactivism movement, as ethically debatable as it is, at least has some rational reason for being. Visa was attacked after suspending payments to WikiLeaks. HB Gary was brought down after claiming they’d infiltrated Anonymous and would reveal the members’ identities. Rightly or wrongly, these incidents had motivation beyond pure pilfering.

But Stratfor? No motive appears to be present and whilst they provide security related services, they don’t appear to be involved in any of the sorts of activities which normally attract the ire of the hacktivist community. Unlike many previous breaches, there has been no “We hacked you because [insert motives here]” statement.

Back in September I wrote about Gootkit attacking ASafaWeb, a project I was working on that was in its infancy at the time. The point was simply that just being on the web is motive enough to be indiscriminately attacked. Automated bots don’t give a damn what your site is, they’ll have a go at you and if any weakness are found you can be sure there’s a human at the other end ready to step things up a notch. That’s all the reason they need.

2. The financial abuse of your customers will extend long and far

Following the breach, the attackers began using customers’ credit cards to make charitable donations. There’s an element of Robin Hood about this – assuming you conveniently overlook the fact that many cardholders will simply report the transaction as fraudulent and have the charge reversed – but the really interesting bit was yet to come. Messages like this started popping up very quickly after the card details were posted online:

And similar on Twitter:

Was this on behalf of the perpetrators? Who knows, could have been anyone, all the credit cards are now available for the world to see right here. The extent of the abuse is only limited to the diligence of the card holder (how quickly they cancel it) and the financial institution (their ability to identify fraudulent activity). tl;dr – this is making for a lot of very, very unhappy customers as the financial abuse extends well beyond just the hackers.

3. Your customers’ other online services will be compromised

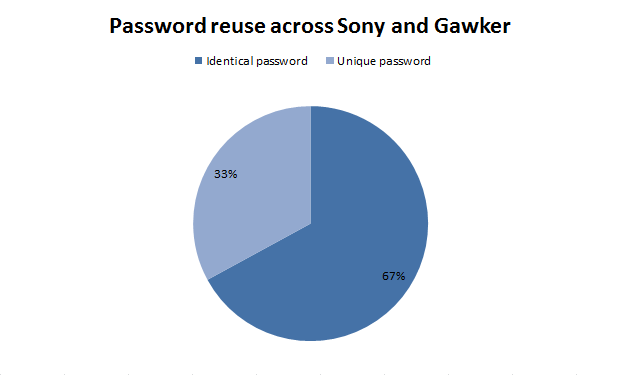

Early this year I wrote about Why your app’s security design could affect sales of Acai berries. In this post I talked about the high prevalence of password reuse as evidenced by the Gawker breach and why the compromise of one website consequently leads to the compromise of accounts on many others.

Then around the middle of the year I did A brief Sony password analysis and found a staggeringly high occurrence of password reuse across email addresses common to both Sony and Gawker:

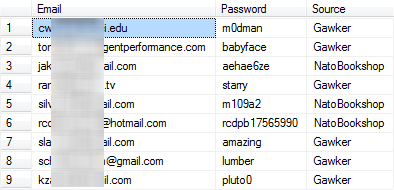

So is it any surprise that a very quick look at the Stratfor accounts cross-referenced with previously breached credentials sources is showing yet more password reuse? Here are just a handful of examples where previous breaches I had on file matched with accounts from Stratfor:

What it means is simply this: because Stratfor did not adequately protect their customers’ credentials and because many of those customers reuse credentials, it’s extremely likely that other non-related services will be breached as a result. It’s also extremely likely the blame for this will be directed at Stratfor.

4. Saltless password hashes are a thin veneer of security

We now know that customer passwords were stored as direct MD5 hashes; there was no use of salts. According to the Pastebin release, 54% of the accounts were easily cracked using a dictionary attack with the UNIQPAS password list. Once you have 30 million real world passwords, hashing and comparing these to a breached database becomes a pretty straightforward event.

Back in part 7 of my series about the OWASP Top 10 for .NET developers about insecure cryptographic storage, I showed just how easily password hashes alone fall to a brute force attack and now we’re seeing this (again) in the wild. Mind you, I also showed how easy it is to create a cryptographically random salt and why any website at all today wouldn’t do this, let alone one the nature of Stratfor, is beyond me.

So the bottom line is this; if you simply hash passwords, you might just about not bother at all, and that’s regardless of the hashing algorithm used. The only thing saving you from a simple brute force attack is if users create strong, unique passwords – which as I showed in the Sony analysis, they almost never do!

5. Your dirty software laundry will be aired publicly

At one time or another, we all end up with some software skeletons in the closet. Whether by our own volition or pressure from others, we take some shortcuts and make some compromises. Sometimes we’ll call this “technical debt”, other times we’ll look back and wonder why we didn’t know better at the time.

Once you’ve been well and truly owned in Stratfor / Sony / Gawker style, that dirty laundry is going to become very, very public. Stratfor did a number of fundamentally stupid things in their website design and those practices are now on show for the world to see. Using MD5 as a hashing algorithm; bad form. No salts used; foolhardy. Storing credit cards in the clear; downright negligent.

So you need to ask yourself this question: if a website I was involved in building was stripped apart and put on public display, would I be able to stand proudly by my code? Or would I be beating a hasty retreat and rapidly removing Stratfor (or equivalent) from my CV?

Summary

This wasn’t intended to be a Stratfor-bashing post, rather it’s an opportunity to see the fate which awaits those who don’t take website security seriously. Call it a quick reality check if you will.

So with that fresh in mind, how well do your sites adhere to the security risks identified in publications like the OWASP Top 10? Are you storing sensitive client data in clear text? Are you simply hashing passwords with no salt, regardless of the algorithm used? Or only slightly worse, are you storing passwords in the clear?

If you can answer “yes” to any of this then now is a great time to have a serious think about investing a little bit of time getting your house in order. Raise it with your boss, chat to your CIO / CSO, talk to anyone who’ll listen because if you’re in the same boat as Stratfor and you get owned, there’s a real good chance your world will change in all sorts of unpleasant ways literally overnight.