Banks don’t get it. Telcos struggle with it. Airlines haven’t got a clue. That’s right folks, its password time again.

Earlier in the year I wrote a little post about the who’s who of bad password practices. I named, I shamed and I got a resounding chorus of support. The point was made.

But it still bugged me. Why were our banks and airlines so consistently forcing us to choose poor passwords? Why do they constrain our length, discriminate against our character types and in some cases, even discard the entire alphabet? I mean there must be a reason, right?

So I asked each one of them.

Please explain

What I did was to go through and query a number of the companies who had decided to forcibly require me to select what I would call a restrictive password, that is one which simply wouldn’t allow me to create the degree of entropy I ideally wanted. Just to be clear, I wasn’t trying to go nuts with 200 character passwords or anything like that, I just wanted to implement a reasonable length (I won’t say how long) and mix up the characters.

I contacted the various customer services channels of each company with a message similar to the one you’ll see below, essentially a little Please Explain regarding their respective password policies. I tailored each one as the various sites implemented different restrictions I wanted to specifically refer to. Let me pick the Telstra one as an example because firstly, it’s pretty atypical, and secondly, they provided one of the stupidest responses so I’m going to draw a little more attention to them.

Here’s how it looks:

| I've just gone to change my Telstra online billing password and have had some difficulty. I'm being told my password is too long then that it contains illegal characters. Unfortunately I can't see any information on the website about how long the password may be or what characters are allowed. |

Concise, courteous and unambiguous. As the responses started flowing in I found they all pretty much fit into one of three clear categories. Let’s take a look at what these are and understand why so many organisations go against the commonly accepted wisdom of good password selection.

Reason 1: Pandering to the lowest common denominator

The lowest common denominator model goes something like this: Think about all the ways that someone might want to prove their identity to an organisation then pick the most basic, insecure method and repeat this across every interface the customer has at their disposal.

In the cases I’ll discuss here, the device with the least fidelity, the lowest entropy and all round most insecure is this guy here:

The humble touch tone telephone is a great device for bringing automated services to the masses but it’s abysmal for entering strong password via the keypad. The problem is that you’re constrained to ten digits and in the world of password entropy, it doesn’t get much worse than that.

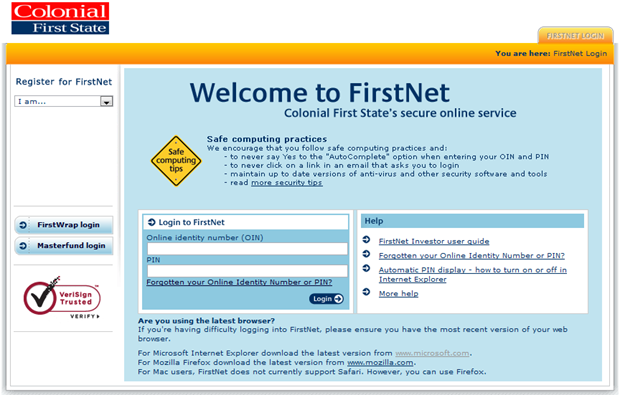

Colonial First State is one of those otherwise fine banking institutions which doesn’t seem to quite get it when it comes to password security:

| Dear Mr Hunt Thank you for your email. I am sorry that we cannot offer alpha-numeric passwords for First Net. At this stage a PIN can only contain between 6 to 8 numbers (no spaces, punctuation or letters). This PIN can also be used to perform transactions over the phone using our automated service First Link. This would not be possible if the PIN contained special characters. However I have passed your feedback on to our IT department for their future consideration. |

This message is actually a little perplexing when their website makes an overt attempt to talk about “Safe computing practices”:

Drilling down into their security tips, we find some insightful guidance:

The easiest way for someone to gain unauthorised access to your personal information is by guessing, stealing or overlooking your password, rather than by accessing your password over the internet

Now call me crazy, but when you’re entering only 6 to 8 characters from a keypad with a total of 10 keys, guessing, stealing or overlooking (I assume they mean “observing”), is a fundamentally more likely scenario than when you have the full gamut of keys on a keyboard at your disposal.

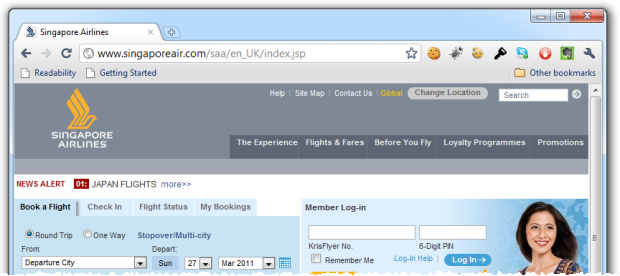

Singapore air is a similar situation to Colonial albeit even more restrictive. It’s six digits all the way here folks and even a lovely, smiling Singapore girl won’t make me forget that this is just not how you want to be setting passwords:

Of course the other fundamentally bad security decision here is that the logon form is not loaded over SSL. Yes, it posts to SSL but as I’ve previously lamented, this is just not enough. The good people of Tunisia can tell you what happens when you have no certainty that the logon form has been loaded without interference.

This is where I would normally copy and paste the response received from SIA and systematically dissect what was wrong with the answer. But I can’t do that with these guys.

Instead of the generic textbook answer that every other organisation performed (and there were about a dozen of them all up), I actually had a call from a very nice gentleman in Singapore. Whilst the personal service was nice, the message was the same: “We want to allow people to use the same password on the telephone keypad”.

I had a candid chat with the guy and explained I spent my days working in the software world so hopefully he didn’t think I was just some loony with a vendetta. But his response was ultimately just textbook stuff all the way down to the “I’ll be sure to pass your feedback onto the IT team” closing message. Is every company working from the same script or something?!

So what’s the answer to the lowest common denominator conundrum? Its simple; a PIN for phone banking and a password for internet banking. Plenty of financial institutions get this right (ANZ, for example). Forcing customers into using what by any stretch of the imagination is the most insecure possible set of rules for a password is both foolhardy and unnecessary.

Reason 2: The combined strength fallacy

The combined strength argument essentially assumes that while your password is crap, when combined with other information or mitigation strategies it becomes, well, a bit less crap. Now in theory, there could be something in this. I mean what’s more secure than one bad password? Two bad passwords!

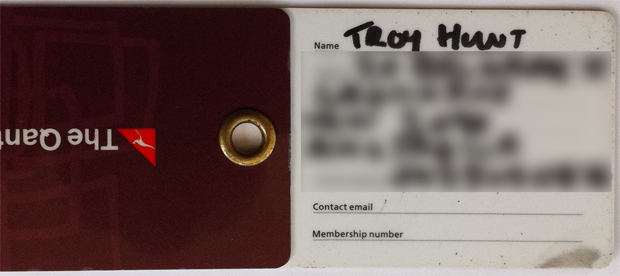

The problem is though, when it comes to Qantas, the other information is just a little bit predictable. Here’s their angle on passwords:

| Dear Mr Hunt, Thank you for your correspondence. The combination of your membership number, surname and 4 digit pin provides a secure verification method and ensures a very high level of security of your account. I have confirmed with our Frequent Flyer team that we have never had any breaches of accounts using this method, however I appreciate your concerns and feedback. As Qantas is continually trying to enhance the design and functionality of the site I have forwarded your comments to the design and development team for their ongoing review. |

I’m going to let you in on a little secret. Here’s what’s hanging off my luggage right now:

Two things stand out here; firstly, the digital age has killed my handwriting and secondly, two out of the three pieces of data required for me to authenticate to Qantas are plain view. Plain view of baggage handlers, plain view of cabin attendants and plain view of other passengers. By pure coincidence, I never wrote my membership number on the tag but what this picture clearly illustrates that this piece of data is hardly considered sensitive.

But as the friendly customer service man has said, Qantas has “never had any breaches of accounts using this method”. That’s kind of the same as me never having made a claim on my car insurance but I still pay it, or never having catastrophically crashed into the ocean on a Qantas flight but I still check where the exits are.

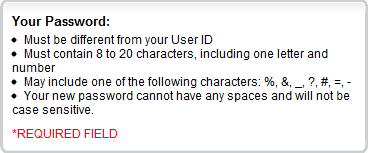

Moving on, I was pretty eager to see the response from American Express and if I’m honest, I was actually hoping to get one like this for the entertainment value alone:

I would like to inform you that our website has a 128 bit encryption. With this base, passwords that comprise only of letters and alphabets create an algorithm that is difficult to crack. We discourage the use of special characters because hacking softwares can recognize them very easily.

The length of the password is limited to 8 characters to reduce keyboard contact. Some softwares can decipher a password based on the information of "most common keys pressed".

Therefore, lesser keys punched in a given frame of time lessen the possibility of the password being cracked.

Fortunately some degree of sanity appears to have prevailed over at Amex and whist I didn’t get a delusional response complete with spelling and grammatical errors, I’m not sure the answer sits real well with me:

| Dear Mr. Hunt, Thank You for contacting the American Express Email Servicing Team in Sydney, I understand your concern is with the recent changing of your Online Profile password. American Express regards its security for all our Card Members with the upmost importance. I appreciate that whilst other institutions may have other specific requirements when changing passwords, our Online Profile website has been designed with the highest level of security and as such has certain requirements that we ask our Card Members to enter. Currently American Express has fraud protection systems that offer the best in security and we also offer a Fraud Protection Guarantee, which means you will not be held responsible for any fraudulent charges, as long as you notify us immediately after you notice a charge you do not recognise and you have taken reasonable care to protect your account details. |

Now just as a little reminder, here’s their policy on passwords:

The good news is that it’s not a PIN (are you listening, Colonial First State?), the bad news is a very limited set of non-alphanumeric characters, no spaces and it’s not case sensitive! That last one just blows me away. I mean, why?

Of course the password rules tell us nothing about the remainder of Amex’s security model and who knows, maybe they do have “the highest level of security”. But unfortunately, credibility is betrayed by the simplest and inane of password rules. If one of the most basic tenets of creating a secure account – good password entropy – is discarded, what else do they just not get?

But the real kicker and the reason for Amex’s inclusion under the “combined strength” banner is the fraud protection. What this says to me is that “Yes, you may get screwed over by your weak(er) password but after that we’ll help you get back on your feet”. To Amex’s credit, I’ve had a very positive experience with them in the past regarding fraud (I suspect a disclosed card number), but of course I would have rather it not happen in the first place.

You see, at the end of the day, by saying “there are other factors which mitigate the password rules”, these organisations are essentially conceding that their password rules kind of suck. It’s an acknowledgement that on their own, they don’t meet the bar. Great, they’ve added mitigation strategies but why not just get the damn password rules right to begin with?

Reason 3: Because that’s just the way we do it

The previous answers “lowest common denominator” and “combined strength” are not good answers; in fact they’re fundamentally flawed. But they are answers which is more than Telstra could muster. How do you think they responded when I asked for information on their password policy?

| Dear Troy, Thank you for your email dated 25/1/11, regarding Online Billing. We sincerely apologize for the inconvenience. We have now taken the liberty to reset your password and provide you a default password. You may just change the password once you logged in to the system. Please log-in using this password: XXXXXXXXX. |

I’m not making this up – honest! Not only did they did not answer the question in any way whatsoever, they reset my bloody password and emailed it to me in plain text! By now I was getting a good idea of Telstra’s approach to security (and customer service, for that matter), but I pushed on anyway:

| Thank you for your response, but unfortunately it has absolutely nothing to do with my question. Let me repeat: "Could you please clarify the rules for passwords and also why they appear to be so restricted on the Telstra website?" I would appreciate an answer to the original question. |

That oughta do it, nice and clear, right?

| Dear Troy, Thank you for your email dated 25/1/11, regarding Online Billing. Please login with the Password provided to you by my collegue, Once you're logged in, please use a password that is alphanumeric, minimum characters is 4, maximum is 16. Please do not place any spaces or special characters. |

And the reason for the restrictive practices is…..? One more go:

| Thank you, but that only answers half the question and raises another one. Could you please clarify: 1. What is a "special character"? 2. Why does Telstra restrict these, and spaces and passwords longer than 16 characters? |

C’mon, I can’t be any clearer than that right? Two simple questions, I' know I’ll get two simple answers any moment now:

| Dear Troy, Thank you for your email dated 27/1/11, regarding Online Billing. Special characters are those characters that is not included in the Alphabet. It includes ">?!@#$%^&*()}{":;<> Telstra Online Billing's Password will only accept alphanumeric characters and a password that is between 4 to 16 characters as a Standard Operating Procedure. |

Ah! Now it makes sense, it’s a standard operating procedure! You see, there is no necessity for the intent of an SOP to actually be understood, it simply needs to be followed. Always. Without exception. I could ask why the SOP is so restrictive but there’s probably another SOP prohibiting them from commenting.

But don’t think that Telstra has a monopoly on poor customer service and screwy policies with apparently no rational bearing, oh no. When I asked TPG (one of our premier ISPs in Australia), why they limited passwords to a range of 6-8 characters in length and only alphanumeric characters, here’s what they thought constituted a legitimate answer:

| Dear TPG Customer, Thank you for writing to TPG Helpdesk. Your password should be 6-8 characters in length and should contain a combination of numbers and letters. All accounts can nominate passwords of only up to 6-8 characters. |

Oh great, here we go again. Let’s take another stab at this:

| Thank you for the prompt response but I think you may have misunderstood the question. I asked why my password must be so limited when good password practices usually prescribe using a wide range of characters - including symbols - and being as long as possible. 8 characters is obviously a very short password when most online services allow many dozens without restriction on character types. Can you please clarify why this is the case? |

That’s a pretty clear question, I even bolded and italicised the important bit so it wouldn’t be missed. They have to give me a sensible answer this time, right? Uh…

| Dear TPG Customer, Thank you for writing to TPG Helpdesk. Currently, that is the rule that is set on the system for setting new passwords but I have already taken note of it and will be forwarding this to our administration department as this will be considered as a feature request as TPG is always looking for ways to improve and enhance features and design. |

Aha! That is the rule! You see, if you press hard enough you always end up with the answer. On reflection, perhaps I should have clarified if there was an SOP behind this?

As I said earlier, these experiences actually tell us a lot more about the customer service than it does their password policy (although the emailed plain text password was somewhat enlightening). So the easy answer to the original question is: “because”. So there.

But what this is really telling us is that sometimes there just simply isn’t a good reason for password policies. Someone at some point drew a line in the sand and decided that was the way things were going to be. What’s unfortunate is that organisations such as Telstra and TPG aren’t able to articulate their position. Who knows, maybe there’s actually a basis for their decision but when you answer questions in the fashion above, you just look plain stupid.

A serious note

This post is intentionally a bit tongue-in-cheek and I don’t have any basis beyond observing password policies on which to form an opinion on the organisations’ security practices.

But the serious note is this: If we – as the technology industry – are to make headway in the application security space and more specifically, around password management practices, we need to be consistent. It’s not good enough to on the one hand, espouse the virtues of password entropy, but on the other hand to say it doesn’t matter as much when combined with other credentials or that after someone breaches your account we’ll help you recover. That’s not where we want to be heading.

The whole thing about having so many online accounts you have to keep track of is hard enough on many people, why do we now need to send out such mixed messages around passwords? Why can we not simply agree that there’s a minimum bar (and this may differ site to site, that’s fine), but then set a maximum length threshold at 20 characters or beyond and within that let people go as nuts as they want? Why be so restrictive?

I’ll take a stab at an answer and say that other than the lowest common denominator issue for which the answer is clear, developers have simply struggled with their own self-imposed limitations. Maybe Amex doesn’t like spaces because they’re causing word breaks, or is not case sensitive due to DB collation or case insensitive string comparators. Maybe Telstra doesn’t like angle brackets because they’re not properly escaping them and they’re messing with their markup. Perhaps it’s the same problem with ampersands.

All these technical problems have already been solved! There are simply no longer good technical reasons in 2011 to disallow these patterns. Why they persist in this day and age is surely reflective of legacy dependencies. But whatever the reason the result remains the same: they’re sending out mixed messages to their customers around the thing they can least afford to be ambiguous about – their security.

Summary

Here’s what I find really bizarre about all this: Why is it that nearly every little el-cheapo piece of forum software allows fantastic password entropy yet some of our largest financial institutions and multi-billion dollar airlines can’t get it right?

And it’s not that I’m saying password strength if the be all and end all of app security either – it’s not. In fact it’s only one very small snippet of a much bigger picture. But it’s one of the few things system users actually have some control over. It’s the one time we – as those responsible for designing and building software – actually ask our users to make an important decision that can have a real impact on their overall online security.

Which brings me all the way back around to consistency again; until we build a better mousetrap, we’re stuck with passwords. That’s the status quo for now, let’s try and do it as well as we possibly can and that means helping people to exercise all those good password entropy rules we keep drilling into them. “Because” is no longer a good enough reason not to.